Some Kids with Disabilities Can’t Learn at Home. Parents and Advocates Want to Know: What’s the Plan?

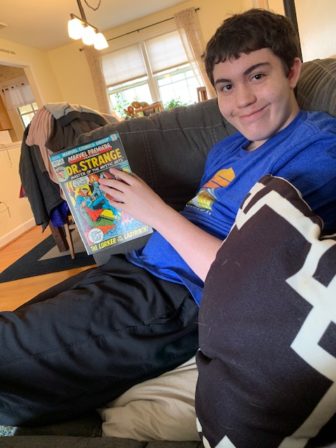

Jen Sherman and her son, Gavin, 14, are sheltering in place at their West Hartford home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gavin is a special education eighth-grader at King Philip Middle School and is now doing distance learning at home. His mom is working from home putting in about 60 hours a week, struggling to work and help Gavin at the same time. “Gavin needs routine and structure,” said Jen Sherman. “Its going bonkers for me,” said Gavin. “I’m at home for four weeks now and can’t see my friends.” Photo credit: Cloe Poisson, CTMirror.org

A West Hartford eighth grader – and his mom – among those struggling with online-only education and therapy.

By Jacqueline Rabe Thomas, CTMirror.org

Parents whose children have severe disabilities are in survival mode.

The experts they relied on to help educate and socialize their children – and who provide them with a little respite – shut down in-person programs when COVID-19 touched down in Connecticut. School and therapy may be available online now, but their children struggle with that platform.

The result: children are regressing more and more the longer school is closed.

That means hours-long temper tantrums for an autistic girl in Bristol yearning to see her classmates. A 12-year-old in Darien with emotional disturbance challenges is unable to cope with the change and has once again started to bite and hurt himself. Sometimes he hits his mother. In West Hartford, an eighth-grade boy with autism began retreating after seeing people wear face masks and often refuses to do his school work.

“My kid is falling apart in front of my eyes. It is making me physically ill,” said Jen Sherman, whose son Gavin is a special education student who struggles with change and disruptions to his routine. “He’s just deteriorating on me. His mental health is definitely concerning. It’s the unknown. He has so many questions that we can’t answer.”

Jen Sherman and her son, Gavin, 14, are sheltering in place at their West Hartford home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo credit: Cloe Poisson, CTMirror.org

“It’s going bonkers for me,” said Gavin. “I’m at home for four weeks now and can’t see my friends.”

Statewide, about 79,000 children have a learning or physical disability and, before the pandemic, were receiving specialized programing or accommodations at school. A large share of these students can benefit from the remote learning being provided by districts, such as those with speech impairments or physical deformities where a hearing aid or wheelchair can bridge the divide.

But for the 18,716 children with autism, emotional disturbance, or an intellectual disability – one out of every 28 students in Connecticut’s schools – accessing education from a distance is either incredibly difficult or impossible.

“There is a whole subset of kids that simply will not be able to access any kind of remote learning, whether it’s through a computer or work packets that are sent home,” said Christina Ghio, an attorney who represents children with severe disabilities. “Parents are going to have an incredibly difficult time trying to put structure in place at home because they don’t have the specialized skills that their schools have.”

Sarah Eagan, the state’s child advocate, agrees.

“There are children that just can’t be home all day without support, period. We know that,” Eagan said. “So how do we meet those needs? We need to find the answer.”

Federal law requires children with a disability have access to an “appropriate” education and if a school district fails to deliver that “free appropriate public education,” parents can obtain “compensatory educational services.”

With school closures now into the second month – and indications from Gov. Ned Lamont that school may not reopen this academic year – parents and advocates want assurance that the state has a plan to help students struggling with distance learning. Suggestions to provide “compensatory education” range from providing extra summer school, having students start the next school year early, or to begin offering students one-on-one in-person sessions.

“We need to ensure that students who haven’t had any choice – and have been inappropriately placed in distance learning – are able to recoup those skills that they may have lost,” said Marisa Halm, an attorney with the Center for Children’s Advocacy who represents children from low-income families.

Gavin’s mother would like the summer program his district typically provides to have an educational component.

But officials at the state and federal education departments have been silent about whether they will require local districts to provide any additional instruction, or if they will incentivize them to do so with funding. Instead, education officials have instructed district leaders to provide equal access to remote learning to students with disabilities and left it up to them how that will be accomplished.

They’ve also relaxed timelines and processes that districts must typically follow under state and federal laws – decisions that have frustrated many advocates.

“Are we really as a nation going to tell this cohort of students, ‘Sorry, we didn’t get to it that year’?” said Kit Savage, who has a child with a disability and also helps fellow parents advocate for their own kids. “I’m not hearing districts and state departments saying, ‘Relax parents, whatever we can’t handle now, we are going to make sure all students receive it soon.’”

Federal law typically requires that parents and school officials meet within 10 days if a child’s school placement changes – in addition to the required annual meeting – to come up with a plan for what services and supports the school will provide a child with disabilities. With the somewhat immediate school closures, the state department of education has told districts that these meetings – called Planning and Placement Team [PPT] meetings – are not required, even through video conferencing or by telephone during the pandemic.

“They are operating really in the netherworld right now,” said Andrew Feinstein, a special education attorney.

Parents and advocates also worry that a provision in the federal stimulus bill passed in late March is a harbinger to relieving districts from having to make up the education students weren’t able to access during the pandemic. That provision asks U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos to issue a report within 30 days containing recommendations to relax sections of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, to “provide limited flexibility” to states and school districts during the emergency.

A lack of federal guidance

Audra Talbot yearns for even a short break. This single mom, who has two children with autism and other disabilities, is struggling and has almost no support. Her 10- and 12-year-old children both need constant support to complete most tasks, manage behaviors, and complete the lessons the schools send home.

Audra Talbot’s 10-year-old daughter Grace, left, and 12-year-old son Sam, doing fluency drills for reading and speech. Talbot sends videos to his teacher everyday to help her problem solve. Courtesy of CTMirror.org

“I feel like my finger’s in the dam in a way, and I keep trying to put my finger in another crack, trying to stop the dam from exploding,” said Talbot, who lives in Bristol.

The federal Care Act does provide billions for education and largely leaves it up to local school districts and governors to determine where to spend it. The chief financial officer of the state’s education department estimates that $111 million is headed for Connecticut’s K-12 school districts. However, guidance released by the State Department of Education Tuesday afternoon informed district leaders that they need not spend the additional aid to “supplement” existing services. The guidance also made clear the decision on how to spend the additional aid will be left to local officials.

Also included in the federal stimulus for education is another $27.8 million for the governor to spend on either K-12 or higher education. This federal funding cannot be used to plug any state budget holes the pandemic has caused unless the U.S. Department of Education grants the state a waiver.

“I want to encourage each and every governor to focus on continuity of education for all students. Parents, families, teachers and other local education leaders are depending on their leadership to ensure students don’t fall behind,” DeVos said Tuesday when announcing how states can apply for the aid.

While officials determine how to spend the additional federal funding, Connecticut’s education commissioner, Miguel Cardona, went on Twitter recently and let parents of children with disabilities know they are a priority.

“For the parents of students of special needs: I see you and I hear you. Right now our efforts are going to be focused on making sure we are providing services and support to students with special needs, to our English learners and our youngest learners in early childhood programs,” Cardona said.

The administration of Gov. Ned Lamont has begun to signal it is eyeing an expansion of summer school programming for students with disabilities and others who struggle to access education remotely.

“Summer school seems imperative. Work-study programs for the summer are imperative. I’ve got to get kids back into a routine as soon as I can. That’s a priority,” Lamont told reporters last week when asked whether he has plans to provide students struggling with remote learning any additional compensatory education. Lamont said he is also encouraging The Partnership for Connecticut, the collaboration between the state and billionaire philanthropist Barbara Dalio, to use some of the millions it has available to provide robust summer programs.

Fran Rabinowitz, the leader of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents, said district leaders are ready to provide additional summer programming – if they are given funding to do so.

Jennifer Sherman’s son Gavin doing some silent reading. Courtesy of CTMirror.org

“Do I think we’re going to need additional support for kids? Without a doubt. I just don’t know where the dollars are going to come from or whether it’s going to be safe this summer to provide that. Hopefully it will be,” said Rabinowitz. “Distance learning I think is wonderful, and we’ve done great moves in this, but I still think we’re not reaching all of the children every day. But perfect can’t be the enemy of the good. I hope that everyone understands that funding and resources are going to be necessary to close the gaps that this situation has brought about.”

Jennifer Sherman, who is also a Hartford teacher and a leader of a special education parents’ group in West Hartford, urges people to remember that everyone has the best interests of the children in mind.

“I think that everyone’s trying to do the best that they can and I think that no one could plan for this type of closure,” she said, pointing out that because she is a teacher her son is able to somewhat continue his education. “I think that we’re all just trying to survive.”

Reprinted with permission of The Connecticut Mirror. The author can be reached at [email protected].

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.