Bristow: A Man Who Bridged Cultures, and Bought his Way to Freedom

Audio By Carbonatix

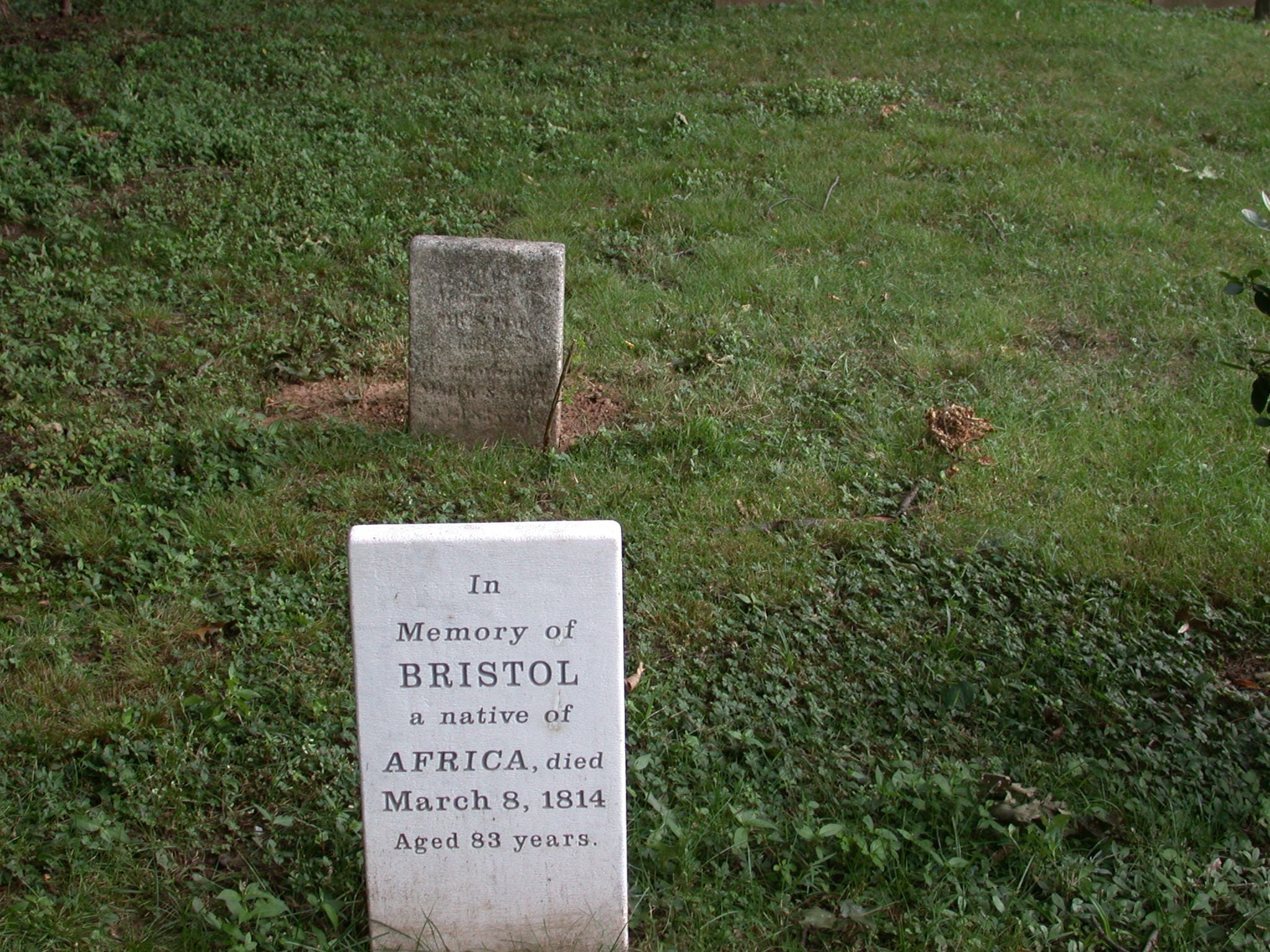

This gravestone was added to the Old Burial Ground in 2004 when the original, now at Bristow Middle School, broke off at the ground level. His name has been spelled variously as Bristow, Bristol, Bristoll, and Bristo. Courtesy of Tracey Wilson

February is Black History Month, and this piece has been submitted by West Hartford Town Historian Tracey Wilson. A version of the article originally appeared in West Hartford LIFE in November 2004, as well as in her 2018 book “Life in West Hartford.”

The Witness Stones have been placed next to Bristow’s headstone, which is located in the northwest corner of Old Center Cemetery on North Main Street. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

By Tracey Wilson, Town Historian

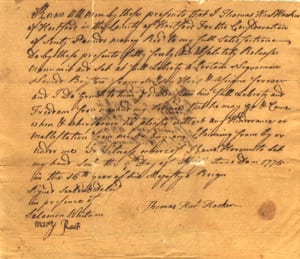

Bristow, an enslaved African aged 44, bought his freedom from Thomas Hart Hooker in 1775. Imagine the human dynamics of this manumission transaction. His manumission paper, in the Connecticut Historical Society, approximately 18 centimeters in length and of paper yellow with age reads:

Courtesy of Tracey Wilson

Know all men by these presents that I Thomas Hart Hooker of Hartford in the County of Hartford for the consideration of Sixty Pounds money Rec’d to my full satisfaction – do by these present fully freely and absolutely release manumit and set at full Liberty a Certain Negro man Named Bristow from (?) to my house & assigns forever and I Do Grant to him said Bristow his full Liberty and Freedom from me and my Service that he may go & come when & wherever he pleases without any Hindrance or molestation from me or any one claiming from by or under me. In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand seal the 9th day of May Anno Dom 1775 in the 16th year of his Majesty’s Reign.

Signed, Sealed & Deli’v

In presence of Thomas Hart Hooker

Salomon Whitman

Mary Root

Did Bristow know what freedom was while enslaved? Did he understand it once he had his freedom? His manumission paper clearly states what freedom included:

- Being at full liberty from Hooker’s house forever

- Having freedom from service to Hooker

- Going and coming when and wherever he pleased without any hindrance or molestation from Hooker or anyone claiming to be working for Hooker

When I studied slavery with my students, I often asked if they think enslaved people can understand freedom. Some students argued that not having freedom allows a person to understand the concept better. Others said that if a person can see his/her master’s freedom, s/he can know what it is. Still others argued that a person can only know what freedom is when they have it.

Thomas Hart Hooker, the enslaver of Bristow, was 30 years old in 1775 at the time of Bristow’s emancipation. He was the great-grandson of Thomas Hooker, one of the original English settlers in Hartford. Thomas Hart Hooker married Sarah Whitman Hooker six years earlier in 1769 and they had two children, Abigail, born in 1770 and Thomas Hart Hooker, Jr. born in 1772.

At a point in time before 1775, Bristow had come to be enslaved by Hooker. This was not an unusual event in the West Division of Hartford. The pastors, Benjamin Colton (1713-1759) and Nathanael Hooker (1759-1770) each enslaved men. Africans who were enslaved were present in both Hartford and the West Division and it was the economic and political leaders of the day who enslaved these Africans and their descendents who were often referred to as “servants.”

In December 1774, many colonists agreed to stop the importation, exportation and consumption of British goods. But even after the first battle of the war at Lexington and Concord April 19, 1775, most Americans believed that the British would change their ways. They remained loyal to England and thought that the Parliament would treat the colonists more fairly.

Hooker enlisted in the Hartford militia as a private soldier at “first call” in 1775. His wife, two children and maybe some other “Negro” servants were left home, but Bristow would have been free. With a wife and two children aged 5 and 3, Hooker went to war less than a month after the battles at Lexington and Concord. Thomas Hart Hooker participated in the siege of Boston and died of disease on November 11, 1775. His body lies in an unmarked grave in Roxbury.

Hooker’s genealogy says that “before going to the seat of war he gave freedom to his negro servants saying that he would not own property in a human being while he, himself, was fighting for freedom.” The lore about Bristow was that Hooker bestowed freedom upon his “negro servants.” Bristow’s manumission paper reveals a story of Bristow’s freedom that directly challenges Hooker’s genealogy.

What makes Bristow’s manumission document so significant?

What surprises me the most was Bristow’s ability to buy his own freedom. He earned 60 pounds to pay Hooker. This was a large sum of money, especially for someone who was enslaved.

One day’s work was worth three shillings, according to account books from the time period. At 20 shillings per pound, Bristow paid 1,200 shillings or the equivalent of 400 eight-hour days of work. (At minimum wage in 2004 that would be close to $25,000.)

This document is also significant for its use of “republican discourse” which had crept into American political and social life since the mid-18th century. This was rhetoric different from that of England. The colonists established new norms for behavior in America. The use of the terms “set at full liberty and freedom” are the very words used by the revolutionaries of the day.

The two witnesses to this transaction, Salomon Whitman (perhaps a relative to Sarah Whitman Hooker) and Mary Root witnessed this economic transaction when Bristow paid his sum of money to his master. Women had few political rights, and yet Mary Root was allowed to be a legitimate witness for the transaction.

According to law, Hooker could not manumit Bristow unless Bristow could take care of himself. It seems, from reading Bristow’s will from 1791 (16 years later), that Bristow then went to work for Thomas Hart Hooker’s brother, Roger.

Roger, according to the Hooker genealogy, was born in 1751, and was six years younger than his brother. He made 11 voyages to the West Indies before the Revolutionary War. What did the colonists trade with the West Indies? A profitable commodity was Africans.

Historians have claimed that enslaved people in New England were treated as part of the family and were treated better than their counterparts in the South. Numerous runaway ads in the Connecticut Courant and a number of manumissions give us evidence that this was not accurate.

But Bristow’s will shows him bequeathing “all my estate both real and personal unto Thomas Hart Hooker and Abigail Hooker, children of Thomas Hart Hooker late of Hartford.”

Imagine Bristow’s decision. Terry Schmitt, former West Hartford Board of Education member, suggested that Bristow was a man who could bridge cultures and that was why Schmitt said he voted to name the new middle school after him.

Bristow was an African-American who, after buying his freedom, continued to respect and be respected by the children of his enslaver. That could only have happened if this was a two-way relationship from a man who knew what it meant to be free and be human.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford, and click here to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.