Defenders of Open Government and FOI Law in Connecticut Fear the Public’s Right to Know is Being Stifled

Audio By Carbonatix

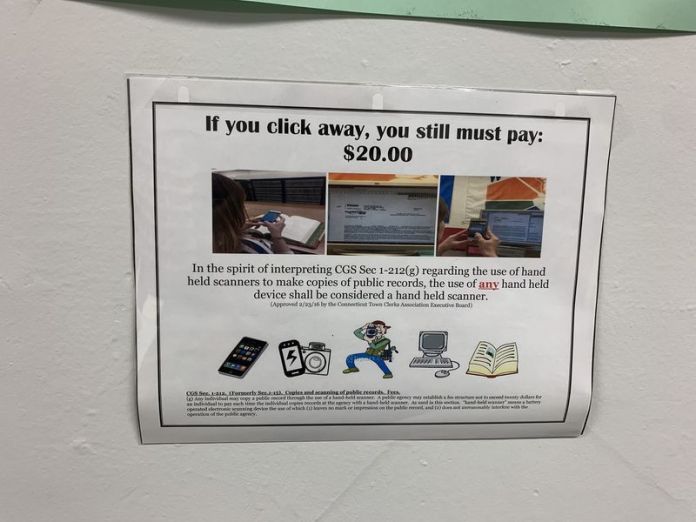

A sign in the Wallingford Town Clerk’s office noting the $20 fee for taking pictures of documents. Gabriella DeBenedictis, Waterbury Republican-American (Courtesy photo)

Exemptions prevent access to certain records, while $20 fees for photographing documents impact accessibility.

By Gabriella DeBenedictis, Waterbury Republican-American

Open government proponents in Connecticut, citing major new barriers to access public records, are concerned that state and local politicians have weakened the Freedom of Information Act significantly over the last year.

A billionaire’s donation with strings attached, union contracts that allow personnel information to be secret, and the use of a stipulation in the FOI law to raise revenue for municipalities are among the growing barriers to citizen access of public records.

The state budget recently signed by Gov. Ned Lamont created the Partnership for Connecticut, a nonprofit foundation that will oversee $100 million donated to the state for public education from billionaire hedge fund founder Ray Dalio. Connecticut has matched Dalio’s donation with $100 million and is hoping to raise an additional $100 million from private donors.

Because the Partnership for Connecticut is a nonprofit, it is exempt from FOI law, despite the fact that it will be overseeing $100 million in taxpayer money and five of its 13 board members will be elected officials. That means Partnership for Connecticut does not have to give notice on its progress, send agendas, or open its meetings to the public.

Michele Jacklin, Connecticut Council on Freedom of Information legislative co-chairman, described the exemption as “precedent-setting.”

“Who is the beneficiary of this money? We have no idea,” Jacklin said. “Presumably it’s going to be for public education for lower-income and disadvantaged students, but we don’t know that. It’s very problematic and we view this as precedent-setting because there’s really no reason to do it.”

Senate President Pro Tempore Martin M. Looney, D-New Haven, said in a recent news conference that Dalio had asked for the FOI exemption. When asked what Dalio didn’t want disclosed, Looney said he didn’t know.

A law stating that collective bargaining agreements involving state employee unions supersede state FOI law came into play this year through an agreement between the state of Connecticut and the state police.

Per the agreement, state police troopers’ personnel files and internal affairs investigations with findings of “exonerated, unfounded, or not sustained” will be hidden from the public. This means no one will know whether the agency exercised proper oversight over officers accused of wrongdoing.

Jacklin said the agreement is problematic because in some cases, an officer is disciplined but not fired, and the public would not know about that discipline.

“The public has the right to know what the state police officer has been accused of, how the investigation is being conducted, what the charges are, whether the employee has been put on probation, whether the employee is being paid, the seriousness of the crime,” Jacklin said. “There are all kinds of details that we would not know because of this supersedence clause.”

For example, when East Hartford resident Michael Picard legally picketed a West Hartford drunken driving checkpoint in 2015, he was detained by troopers for 40 minutes and they confiscated his camera and the gun he had a permit to carry. But the camera was still running, and it recorded the officers saying they had no grounds to arrest Picard and just “wanted to get back at him.”

“Gotta cover our ass,” one trooper was recorded saying. Another suggested they could claim that people who drove past Picard said he waved his gun at them. A third asked if he should call a Hartford police lieutenant about any “grudges” he had against Picard because Picard had protested similarly in Hartford.

When Picard filed a complaint against the troopers, a resulting investigation took several months and the state police refused to disclose the report. The report, which was finally released in November 2017 after a Freedom of Information Commission hearing, exonerated the troopers. Under the new collective bargaining agreement, the public would not be aware of cases like Picard’s.

Connecticut Council on Freedom of Information President Mike Savino said transparency advocates are concerned with FOI law being treated as a bargaining chip through contract negotiations.

“This is public policy, and if lawmakers agree with this exemption they should do it through a legislative process and voting on this law, as opposed to having employees carve it out as a benefit to the job,” Savino said.

A bill aiming to change a law permitting public agencies to charge a $20 fee for taking pictures of public documents with cellphones or cameras died in the Connecticut General Assembly last legislative session after no action was taken on it when it was moved to another committee.

Currently, public agencies can charge individuals $20 for taking pictures of public documents. Though they are not required to charge the fee, many choose to, citing it as a source of revenue for town offices.

State Rep. Michael Winkler, D-Vernon, who wrote a bill that would ban the fee, said he learned about it after a constituent sent him a letter saying it was “ridiculous.” Winkler said his bill would both support freedom-of- information law and save the time of the towns charged with storing the documents, as many towns require someone to sit with a person while they read documents.

“I thought, right now someone could take 200 pictures a lot faster than they could read through it,” Winkler said. “It was a win-win: People could get the documents they need from the government and towns could spend less time sitting with these people.”

Winkler’s bill passed the Government Administration and Elections Committee unanimously and was ready for the House, but the speaker referred it to the Planning and Development Committee, which did not act on it, effectively killing it for the session.

Planning and Development Committee Co-Chairman Cristin McCarthy Vahey said the committee failed to act on the bill simply because scheduling issues prevented them from doing so. There are a certain number of days a bill can be acted on once it is referred to a committee, Vahey said, and on the last day there were a number of bills on the agenda and the committee had a meeting.

“I don’t think there was a conscious plan” to fail to act on the bill, “certainly not on my part or anyone’s part,” Vahey said.

Vahey said she has spoken with Winkler about revisiting the bill and addressing the pushback to it from those concerned with a loss of municipal revenue once the next legislative session starts.

One of those groups, the Connecticut Town Clerks Association, opposes the bill because it would reduce revenue to town clerk offices.

Town officials are allowed – but not required – to charge $1 per page to individuals making copies of documents. A bill abolishing the $20 photography fee would cause individuals to stop paying for copies of documents since they could photograph them for free, argue town clerks, who cite the $1 per page law as a source of revenue.

“We look at it as, if you’re gonna click, you’re gonna pay. And otherwise, we would never receive our copy money,” said Wallingford Town Clerk Barbara Thompson. “If we allowed everybody to make these copies for free, we would never receive any revenue.”

Wallingford’s town clerk office has signs posted that say “If you click away, you must pay” and note the $20 fee, Thompson said.

“It is optional, but in Wallingford we do charge the maximum that we are allowed,” Thompson said. “So statutorily, you can charge up to a dollar for a copy, so we do charge a dollar for the copy. And we do the $20 to click away, we call it the $20 to click away. So if you’re going to take a picture or scan, that’s going to be $20.”

Money from copies and photos goes into cities’ general funds, which Waterbury Town Clerk Antoinette C. Spinelli said is used to offset the cost of maintaining land and other records.

“I don’t think it’s cost-prohibitive for most of us to access a copy of something we need from the town clerk’s office,” Spinelli said. “But the expenses associated with the land records are quite expensive.”

Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin has said he will instruct his city’s town clerk office to stop charging the fee, while New Britain Mayor Erin Stewart believes her city’s office should continue charging it.

Waterbury Mayor Neil M. O’Leary said he understands town clerks’ support of the $20 fee and their use of it as a source of revenue, but said he first and foremost believes in government transparency and believes a government’s main responsibility is to serve and be accessible to its citizens and taxpayers.

“If I have the authority and the discretion to waive those fees for the average citizen and taxpayer and newspaper reporter, I think we should strongly consider doing that,” O’Leary said.

When the next legislative session starts, O’Leary said, he will sit down with town clerks and look for a compromise on the scanning fee that recognizes both the expenses needed to run town clerk offices and the public’s right to access information from their government.

This story originally appeared in the Waterbury Republican-American on Sunday, July 7, 2019. Reprinted with permission.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!