Good News? Teacher Retirement Costs to Surge $100 Million

Audio By Carbonatix

ct.gov (we-ha.com file photo)

The required contribution level is less than what was expected.

By Jacqueline Rabe Thomas and Keith M. Phaneuf,

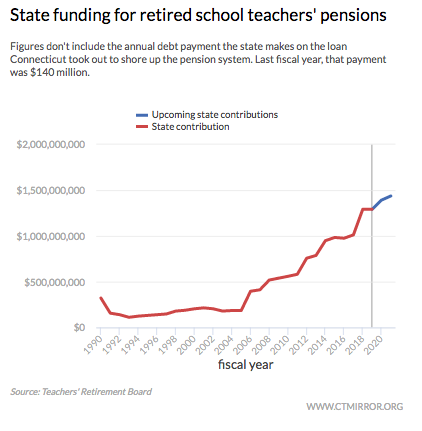

State spending on retired teachers’ pensions is set to surge $100 million next fiscal year – an 8 percent increase the state is obligated to fund.

But, strangely, the spike is good news.

That’s because this single line item in the state budget was anticipated to increase by $163 million next fiscal year.

This new required pension contribution level – accepted by the Teachers’ Retirement Board last week – is $63 million less than what state officials expected to spend when nonpartisan fiscal experts forecasted next year’s deficit last May.

A steeper increase was averted in part by the success of pension fund investments and a cooperative stock market.

According to the latest valuation, investments averaged a 10.76 percent return on market value over the past two fiscal years. By comparison, the average return during the two years prior to that was 1.5 percent.

Throughout most of 2017 and into early 2018, the Dow Jones Industrial Average skyrocketed on its way to hitting several milestones. It cleared 25,000 points this past Jan. 4 and reached record highs 15 times this calendar year.

Connecticut is required to contribute what independent pension fund analysts recommend. That’s because in 2008 the legislature and then-Gov. M. Jodi Rell approved about $2 billion in borrowing to bolster the teachers’ pension fund that suffered from decades of inadequate contributions. In the bond covenant – the contract between the state and its investors – Connecticut pledged to contribute the full amount recommended annually by fund analysts.

That required contribution to the teachers’ pension fund will increase from $1.29 billion this fiscal year to $1.39 billion in the fiscal year that begins July 1. The next year, costs will increase by another $45 million.

The lower-than-expected pension contribution costs will shrink a significant deficit in the two-year budget Gov.-elect Ned Lamont and the legislature must craft starting in February.

State finances, unless adjusted, already are on pace to run $2 billion in deficit in 2019-20 and $2.4 billion in the red in 2020-21, according to the legislature’s nonpartisan Office of Fiscal Analysis, operating shortfalls of about 10 percent and 12 percent, respectively.

But Connecticut also has significant reserves to mitigate this problem. The state holds $1.2 billion in its rainy day fund and is projected to add another $900 million to the emergency reserve after this fiscal year. Analysts also recently upgraded their state revenue forecast Tuesday for the next two fiscal years. If those potential revenue gains are considered, then the projected deficits shrink to $1.6 billion and $1.9 billion, respectively.

State lawmakers in recent years have been forced to make large contributions after decades of lawmakers promising future benefits to retired teachers while not setting aside funds to pay for them.

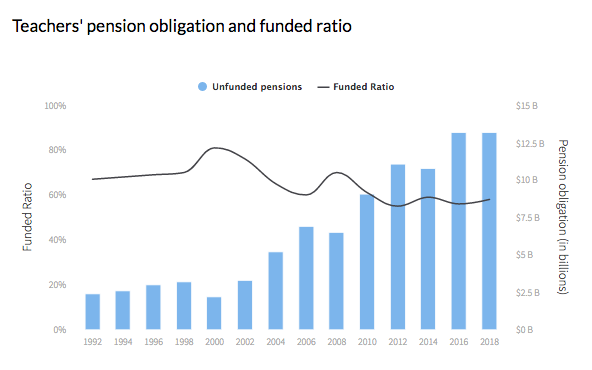

The state owes $13 billion more than the current pension fund holds, which means the fund is only 58 percent funded.

The fiscal hit the fund took during the recession also drove up required contributions. Between fiscal years 2008 and 2016, the required state contribution nearly doubled from $518.6 million to $1.01 billion.

The fund losses mirrored problems experienced by nearly all states in the last recession. The fund uses contributions from government and from teachers, as well as investment earnings, to pay an average annual pension of $60,800 to about 37,000 retirees who do not qualify for Social Security because they were teachers; teachers don’t pay into Social Security.

When earnings fall, contributions typically rise.

Teacher pension contributions are expected to continue to surge, with one study prepared for the state in 2014 estimating that annual costs will reach $6.2 billion over the next 15 years if no changes are made.

Legislators required teachers to increase their contributions to the fund from 6 percent of their annual salary to 7 percent – a $775 yearly increase for the the average teacher and school administrator – when it was implemented last year.

Those increased contributions from teachers barely made a dent in controlling those costs, however. Facing a deficit, the legislature used those increased contributions to reduce the amount coming from the state budget.

Lamont said during the campaign that he supports channeling the annual proceeds from the Connecticut Lottery – about $350 million a year – exclusively to the state’s starved pension fund for municipal school teachers. Those proceeds are currently routed to the state’s overall General Fund, which funds the state’s annual teacher pension payment as well as other state agencies.

This proposal was first made by the state Commission on Fiscal Stability and Economic Competitiveness last year.

Under this scenario, the legislature could assign lottery proceeds for the next 10 years to the teachers’ pension – a revenue stream likely worth more than $3.5 billion over the decade. And while it would take 10 years for the pension system to receive all of those funds, the fund’s assets, on paper, would jump by the full $3.5 billion right away. This would raise the fund’s overall fiscal health, and possibly give the state more options to restructure annual pension contributions.

“Move the lottery. That’s supposed to be for education,” Lamont said during an interview last month. “That would give me enough of an asset base that I could renegotiate with [the lottery proceeds] being on the Teacher Pension Fund. If I could do that, I could stretch out the payments over a longer period of time.

Reprinted with permission of The Connecticut Mirror. The authors can be reached at [email protected] or [email protected].

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!

So NOW the conversation shifts to funding the pension? Here’s a homework assignment…. figure out WeHa’s share of this pension burden…ultimately, they will push the burden to the towns when the state loses access to the capital markets. The latest gubernatorial election shouldn’t have been about ‘national politics’, it should’ve been a landslide for the side that was willing to balance a checkbook. Ridiculous, and losing faith.