Learning a Casualty Of COVID for Students with Disabilities

Audio By Carbonatix

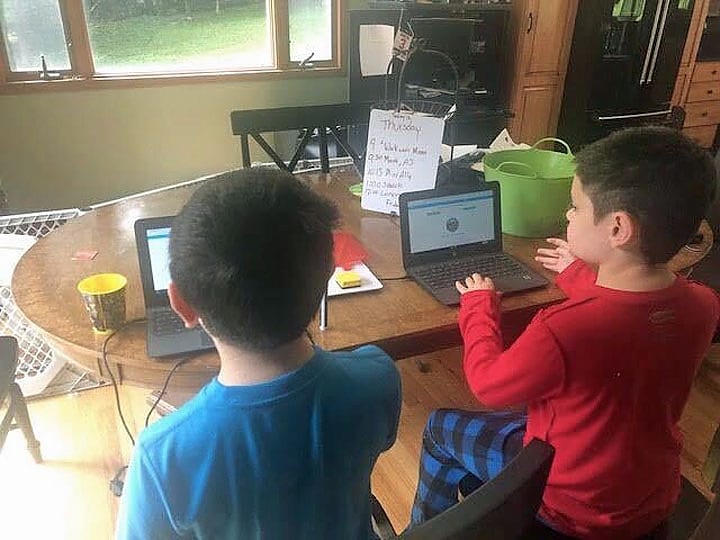

Tracey Ruscil’s boys. Courtesy photo

Parents across the state and the country have expressed frustration about virtual learning along with fear that their kids are falling behind. But for children with special needs, these concerns are exacerbated.

By Emily DiSalvo, CTNewsJunkie.com

As remote learning continues in summer school programs and remains a possibility for the upcoming school year, parents of children with disabilities call the system a “disaster” that fails to provide students with services they are legally entitled to and desperately need.

“My children have both lost skills, they have had behavior issues, bed wetting, self-injurious behaviors since this started,” said Tracey Ruscil of New Milford, the mother of two 10-year-old boys with autism.

Many children with disabilities attend school with an individualized education plan (IEP) that outlines the services they must receive in order to access a free and appropriate education (FAPE). It is designed by a student’s special education team with input from their parents. During a normal school year, an IEP will include services like speech language pathology, special education, occupational therapy (OT), and physical therapy (PT). While these specialists have often done their very best to provide meaningful virtual services throughout the pandemic, parents of children with IEPs attest that virtual learning does not work for their children.

Since schools closed in March, special services like OT, PT, and speech have been provided virtually in various ways. In many cases, the provider would send the parent some ideas of activities to work on at home. For example, a PT may suggest passing a ball to practice motor skills. An OT may provide fine motor activities via email. In other cases, the therapist will meet with the child on a video call.

However, this puts the responsibility of coordinating – and even providing – the therapy on parents since the provider is not there to assess how the child is performing the task, if it needs to be modified or if they are even doing it.

While Ruscil said she is trying her best to attempt the activities that the therapists and teachers suggest, she feels that her efforts are not rewarded with learning.

“I have a sheet of paper that says, ‘Ask questions about what, when, and where,’” Ruscil said of speech therapy assignments. “I can ask them, but I don’t know any strategies that a teacher would know. For PT and OT, I can tell them to jump rope and do sit-ups but I don’t know what I am doing.”

For Ruscil, the start of the pandemic has taken a massive toll on her kids and on her mental health.

“I am terrible,” Ruscil said. “I had to up my anti-anxiety medicine. I’ve had to halfway quit my job. I’m a Realtor and I can’t work as much, so I am going to lose money and it’s awful. I had to become a full-time teacher.”

Ruscil is not alone. Parents across the state and the country have expressed frustration about virtual learning along with fear that their kids are falling behind. But for children with special needs, these concerns are exacerbated.

Nanfi Lubugo, co-executive director at PATH Parent to Parent/Family Voices of Connecticut, a parent support group that Ruscil is involved in, acknowledged that the past several months of virtual learning were difficult for every family but emphasized that the families she works with face a unique struggle.

“It was not adequate for any child, it was grossly inadequate for kids with disabilities,” Lubugo said.

Carmela Mangini, a parent of two children with IEPs said that her son, who has autism, was on a “downward spiral” even before COVID-19 hit Connecticut. Closing schools made matters worse because the virtual workload was piling up. A provision in his IEP allowed for reduced workload.

“We reduced the workload,” Mangini said. “That didn’t work. He needs one-on-one. I am not going to sit here and force him to be on the computer all day long if he is not doing the work. These teachers need to get online and do the work with him.”

Mangini made a schedule in which his teachers met with him one-on-one virtually, which drastically improved his performance, but Mangini still calls the distance learning experience a “disaster.”

“The support just wasn’t there until I pushed for the support he needed for distance learning but also needs when he’s back at school,” Mangini said.

Verna Killian, whose son suffered a stroke at birth leaving him with physical, speech and learning challenges, said that educating her son at home has made her want to do more to support teachers.

Owen Killian. Courtesy photo

“They do deserve more than people give them credit for, a raise for starters,” Killian said. “I have trouble with just my son. They handle over 20 kids, get them in routines and on task. I don’t know how they do it.”

During distance learning, the state department of education required that all special education services outlined in a child’s IEP be provided to the greatest extent possible in a format compatible with virtual learning. The proposed modified plan was documented by the IEP team on the “Student Continued Education Opportunity Plan” form which supplements but does not replace the child’s regular IEP.

For a student receiving specialized services, the form would list each service and the modified plan, as well as who is responsible for creating the plan. For example, the service could be “physical therapy” which would correspond to a goal number from the child’s regular IEP. The method of instruction could be “emails with exercise suggestions and one weekly Zoom meeting.” The person responsible for developing the plan is listed as the physical therapist, but what the form fails to reflect is that the burden falls on the parent to make it happen.

Making it happen is easier said than done. Ruscil said that even audio feedback on a video call with a teacher can upset her sons, making the well-intentioned session a bust.

“With sensory issues, if there’s a reverb, there’s an echo it can throw the entire thing off course just because of a sound,” Ruscil said. “One of them might scream and the other might get up and run away. To try and keep them seated myself is difficult.”

The disconnect for parents is that the state does not document what and how much was actually accomplished in the modified virtual format. Each service on the IEP may have a virtual counterpart, but parents question its effectiveness. According to parents, computer-based activities are a frustrating substitution for individualized instruction.

Those providing the virtual services know they aren’t perfect. At Clifford Beers Clinic in New Haven, Dr. Naomi Libby, a psychiatrist, said that working with kids with autism often requires hands-on support.

“It requires a moment-by-moment response to behavior,” Libby said. “That’s why those services were often done in the home. That has been much more difficult to do virtually. A lot of that has focused on parents and helping the parents address the behavior.”

Lubugo said that virtual education demands too much of parents.

“We’re not teachers, we are parents,” Lubugo said. “We can assist our children but when you ask us to start educating them and supplementing their education, we just don’t have the training for that.”

In addition to lack of training, many parents just don’t have the time due to jobs, medical appointments, and other kids. Ann Smith, executive director of AFCAMP (African Caribbean American Parents of Children with Disabilities), has been reaching out to parents in her network to understand what they are feeling during this time.

“Anxiety, frustration, being overwhelmed,” Smith said. “These are the experiences that our families are having. These are intense, challenging times and being able to manage that and juggle all of these balls at the same time when you don’t have all of the resources available to you – that is what we are hearing from parents.”

Killian said she has been feeling many of these same emotions, but she also sees the stress reflected in her son.

“I’m scared he will lose what he’s learned but I want him to be able to progress and I don’t know what the next step is,” Killian said. “I don’t want to push too hard because we both end up crying if I do, and that’s not healthy for either of us.”

For some kids, the issue isn’t that the IEP goals aren’t being met – it’s that they aren’t able to access virtual learning at all. Jennifer Strychalsky has a daughter who has autism and is completely non-verbal.

“She does not attend to a computer screen,” Strychalsky said. “Whether it is someone live or not. It didn’t work. … It took a couple of months before she would even come to the computer and wave to her teachers.”

The school Strychalsky’s daughter attends offered her virtual speech therapy, OT, and PT but she declined because she knew it would not work virtually.

“She has had zero instruction,” Strychalsky said.

In her daughter’s IEP, Strychalsky said her daughter is required to receive two hours of speech, 90 minutes of OT, some PT, and one-on-one training with an applied behavioral analysis trainer as well as time in class with her special education teacher. She also spends time working on life skills like ordering at a restaurant using her adaptive speech device.

“We worked on all of those things, but there was no instruction,” Strychalsky said. “I know the teachers would have come to our house if they could because they knew she needed services but there was nothing they could do.”

Summer School

Depending on the school district one attends, plans for summer school vary. Many children with an IEP attend summer school as an extended school year (ESY) program.

Gov. Ned Lamont decided that in-person summer school could resume on July 6, but some districts decided to continue with virtual education only.

Lubugo said that months of virtual education this spring led many parents she works with at PATH to opt out of the ESY program.

“For the most part, they are not comfortable sending their children to camps or (in-person) summer school,” Lubugo said. “Some families were so exhausted doing tele-education and when summer time came they said we’re done we need a break. It was too stressful. They opted out of that and are scared to send their children on buses and to school.”

State Child Advocate Sarah Eagan said it is crucial that school districts and state departments use the summer to collect data on ESY programs that service children with IEPs.

“It’s hard to gauge without seeing the information from the State Department of Education how many districts are providing in-person and how many they are providing virtual to,” Eagan said.

Peter Yazbak, director of communications at SDE, said the department will be reaching out to superintendents to collect data on participation rates for summer school as well as ideas for planning for a fall reopening.

The decision to send one’s child with special needs to school is a difficult and personal one.

Regardless of the decision her school district makes about the fall, Killian said her son will not be returning to school in person because of high-risk family members that live with them, so there is no end in sight.

“Without being around friends and other children he doesn’t have the chance to practice the skills he has learned over the years,” Killian said. “Not to mention, he misses his friends. I have to be extra careful and cautious with him due to his health but our house is labeled high-risk. Not just because of Owen but also now my grandmother living with us. So friends weren’t allowed to come to our house nor was Owen allowed to leave the house unless a medical necessity.”

Like many parents, Ruscil is scared about the school year ahead because of the dangers of COVID-19. Nonetheless, she said she is even more scared about what keeping her kids home again would mean.

“You are looking at a bunch of people in a difficult time willing to risk their kid get COVID because the imminent danger is losing skill and self-injurious behaviors,” Ruscil said. “That is happening whereas COVID probably won’t because it’s a (small) chance. It is a 100% chance that my son is hitting himself.”

Republished with permission from CTNewsJunkie.com, all rights reserved.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.