MIRA Plant a Symbol of State’s Struggle to Move into 21st Century

Audio By Carbonatix

Steam billows from a tall stack near the power block facility at the MIRA trash-to-energy facility in Hartford’s South Meadows. Shredded trash is moved through an extensive conveyer system, visible at right, from the tipping floor on the waste processing side (off camera) to the power block facility where it is converted through combustion to RDF, or refuse derived fuel. Photo by: Cloe Poisson (Courtesy of CTMIrror.org)

Waste systems in Connecticut are reaching a tipping point, raising the question of whether it’s time to reinvent how we get rid of our trash. West Hartford Public Works Director John Phillips weighs in on the discussion.

By Jan Ellen Spiegel, CTMirror.org

The Materials Innovation and Recycling Authority plant is a hulking presence on the Connecticut River along Hartford’s southeast flank – a sprawling complex of buildings and emissions stacks that was constructed for another time and use.

It shows.

In the winding corridors and rooms of this fortress-like structure – which originally burned coal to make electricity and now burns trash to generate a small portion of the state’s power – ceiling tiles are stained and warped after years of absorbing explosions from objects like gas canisters that mistakenly wind up in the waste stream. It’s noisy and it smells, though given the nearly 3,000 tons of trash cycled daily through cavernous holding areas across what seems like miles of conveyors and into the incinerator next door, logic says it ought to smell worse.

A several month shut-down in late 2018 due to a particularly acute recurrence of age-related mechanical problems have escalated concerns over delayed plans to update or replace the plant. The current rebuilding plan, while not finalized, has been met with objections over its cost and size.

For many, the MIRA plant, the largest of five still functioning trash-to-energy plants in the state, has become a symbol of what’s wrong with Connecticut’s waste system.

But it may actually raise fewer questions about whether burning trash is still the right approach in the face of catastrophic climate change than it does about how Connecticut should be collecting and managing the various components of its waste stream.

Lee Sawyer, now chief of staff to the commissioner of the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and a trash expert at the agency since 2014, gave an unequivocal “yes” when asked whether the MIRA crisis could be an inflection point for trash handling in Connecticut.

“The potential unsustainability of our overall waste system can no longer be ignored and the challenges at the MIRA facility have demonstrated that,” Sawyer said. “It should be a wakeup call.”

Two workers who maintain the combustion boilers at the MIRA trash-to-energy plant in Hartford walk through the cavernous turbine hall where shredded trash is burned and converted to power that is provided to the state. The hulking brick structure was built in the 1920s, originally as a coal-burning facility. Photo credit: Cloe Poisson (Courtesy of CTMIrror.org)

The MIRA shutdown in 2018 reverberated through the entire system, increasing costs and the potential for unwanted environmental impacts, he said.

“There is a recognition that it is time to really focus on bringing the regional waste system back into balance.”

Finding that balance could require a wholesale reinvention of the entire process of trash disposal, not just how we get rid of it.

While the practice of burning trash for energy arguably remains the most environmentally-friendly and commercially viable means for dealing with whatever can’t be removed from the waste stream, its emissions still contribute to climate change, though other forms of disposal are less environmentally friendly. The key to making trash-to-energy less detrimental – it does create energy, after all – is to get a whole lot more out of the waste stream first.

“The public policy solution couldn’t be clearer – the technology, economics and the practicality all point to continuing to burn and recover the energy we can’t reduce or recycle,” said Thomas Kirk, MIRA’s president and CEO, who called trash-to-energy “an elegant solution to a serious problem of 40 years ago.”

“The key to successful systems invariably trace back to generator-separated waste,” Kirk said. “Once it’s co-mingled now it’s garbage. Before it’s co-mingled, it’s a potential resource.”

“Generator-separated” means consumers separate their own waste — food, fabric, recycling, and actual garbage — before it is picked up at the curb, resulting in less trash at the end.

Such systems have been used in other parts of the world for many years. The most successful ones involve unit-based pricing – otherwise known as PAYT, or Pay As You Throw. Connecticut euphemistically refers to this as SMART – Save Money and Reduce Trash.

So, the less trash you generate, the less you pay. How do you generate less? You recycle more and spin off other components like food waste, which accounted for nearly one-quarter of disposed waste in Connecticut in 2015 — the most recent survey. That’s the second largest single component, just barely behind paper.

DEEP

Food waste grew to be the second largest component of municipal solid waste between 2010 and 2015.

“Anyone who is moving forward has unit-based pricing – otherwise you can’t really get anything done,” said Kristen Brown, vice president of waste reduction strategy for the consultant group Waste Zero, which has been working with DEEP and dozens of municipalities in the state on revising waste collection strategies. “If you do unit-based pricing – your trash is going to drop in Connecticut 50 percent.”

That means cities and town will pay less in tipping fees – what it costs to dump the trash, which is determined by weight. Despite the cost savings, only two towns in Connecticut have true pay-as-you-throw systems in in place.

“We think that there’s a very, very strong budgetary argument to be made that most municipalities would benefit from unit-based pricing. And it really is up to them to make the case to their residents of why this can work,” Sawyer said. “We can support them in doing that, but they need to take leadership.”

But over and over again, local officials hear the same complaints from residents.

“Social media just kills it,” said Brown of Waste Zero. “People don’t see trash as a cost. They think it’s free and obviously nothing’s free.”

You’re going to pay one way or another

There are 169 cities and towns in Connecticut, nearly all handling trash removal a little differently. About 40%, which accounts for about two-thirds of the state’s waste stream, have municipal collection – some with their own fleets, some through contracts with private haulers. Still others leave it to residents to find a hauler or haul the trash themselves.

Many municipalities embed the cost of trash and recycling pickup and disposal in local taxes – making the cost invisible, though not free. In other towns, residents pay the hauler they choose or the municipality to dump it at the town transfer station, which not all municipalities actually have.

Trash haulers dump their loads on the tipping floor in the waste processing side of the MIRA trash-to-energy plant in Hartford’s South Meadows. An average of 2,500 tons of garbage are dumped and processed daily at MIRA for RDF, or refuse derived fuel. Photo credit: Cloe Poisson (Courtesy of CTMirror.org)

One way or another, recycling goes to recycling centers that separate it and send off the components to the appropriate processing facilities. And one way or another, most non-reusable or recyclable municipal solid waste goes to an in-state trash-to-energy plant like MIRA. But there’s more trash than the plants can handle, so about 20% is shipped by truck or train to out-of-state landfills.

Four of the five trash-to-energy plants are privately owned by two major waste companies – Covanta and Wheelabrator. MIRA, which is quasi-public, and the Wheelabrator plant in Bridgeport each handle about one-third of the trash that is incinerated.

Only a few communities provide incentives for people to generate less trash, and genuine pay-as-you-throw exists only in Mansfield and Stonington, where the town’s unlined landfill was closed in the early 1990s.

Town officials, who had to figure out how to pay for hauling garbage to the new trash-to-energy plant in Preston, gave residents two choices: a tax increase, or a pay-as-you-throw program.

“They chose pay-as-you-throw,” said John Phetteplace, director of solid waste

Since then, residents have had the option of buying a big yellow bag – 33 gallons for $1.25, or a smaller, 15 gallon bag for $.75.

“It basically reduces waste by about 50 percent. It’s so successful when people do it, but people are reluctant to do it,” he said. “Once it’s established, people realize the programs work differently than they think. They think they generate 10 times the trash than they do.”

It’s not that they’ve started recycling all of it, Phetteplace said. “People have just started paying attention.”

An often-cited reason against pay-as-you-throw is that people will put trash in with recycling or dump it on the side of the road or elsewhere. But audits in Stonington have shown the opposite.

“It was pretty remarkable how little recycling was in the trash, how little trash was in the recyclables. Our contamination rates were lower than most other towns,” Phetteplace said.

Mansfield has been at pay-as-you-throw since 1990. It uses five container sizes instead of bags. But before it started residents had to either pay privately for a hauler or pay to bring their trash to the transfer station, so the cost was never invisible.

“I think that made it easier to go to this type of service,” said Virginia Walton, Mansfield’s recycling coordinator.

East Lyme also started a pay-as-you-throw system in the early 1990s, but discontinued it within 10 years. Joe Bragaw, director of public works, said to most people, it just looked like another tax.

“I think it’s going take some political fortitude,” Bragaw said, using often-repeated terminology. “You could lose an election on pay-as-you-throw.”

Stonington charges residents for pay-as-you-throw bags for pickup with recycling. The system has reduced the town’s waste by about 50%. Town of Stonington photo (Courtesy of CTMirror.org)

Since then, efforts to implement pay-as-you-throw have been rejected in New London, Ledyard, Montville, South Windsor and elsewhere.

“There was a lot of confusion on if it was going to be a double tax,” said Tony Manfre, South Windsor’s superintendent of pollution control. “But it’s really not. What we’re doing is reducing our budget.

“Social media kind of got ahead of us,” he added. “Then it just kind of snowballed.”

But nowhere did it fail more spectacularly than in West Hartford. The city, widely regarded as environmentally progressive, offers free curbside textile collection, which includes clothing, shoes and other materials that require sorting. Many residents also pay for food waste pickup from the private hauler Blue Earth.

But pay-as-you-throw was a step too far.

“One-third of the community actually got behind it,” said John Phillips, West Hartford’s public works director. “One-third accepted the fact that we had a problem but wasn’t sure this was the solution. And one-third of the community was no way. No way, no way, no way, no way.”

How can towns educate consumers that pay-as-you-throw will actually save them money? “I don’t know. I thought I knew – but we failed,” said Phillips, who thinks the system is necessary to transform the waste system. “People just wanted to know if their taxes would go down.”

Odds are they won’t, but they might not go up – or go up as fast – if there’s less going to the trash-to-energy facility. Throw in removing textiles, food waste and other kinds of recyclables from municipal trash, Phillips said, and the savings increase.

The MIRA conundrum

Recycling is mandatory in Connecticut for glass, plastic, cans and certain types of paper, all of which generally can be thrown together into the blue bin as single stream recycling. A recycling center then sorts it out for ultimate re-purposing.

A few other items, such as electronics, paint and mattresses, are recycled separately through a system called extended producer responsibility, or EPR, which means whoever made the product takes care of its end-of-life disposal. And the state’s bottle bill allows certain cans and bottles to be recycled at a point of purchase where the deposit paid on those containers can be refunded.

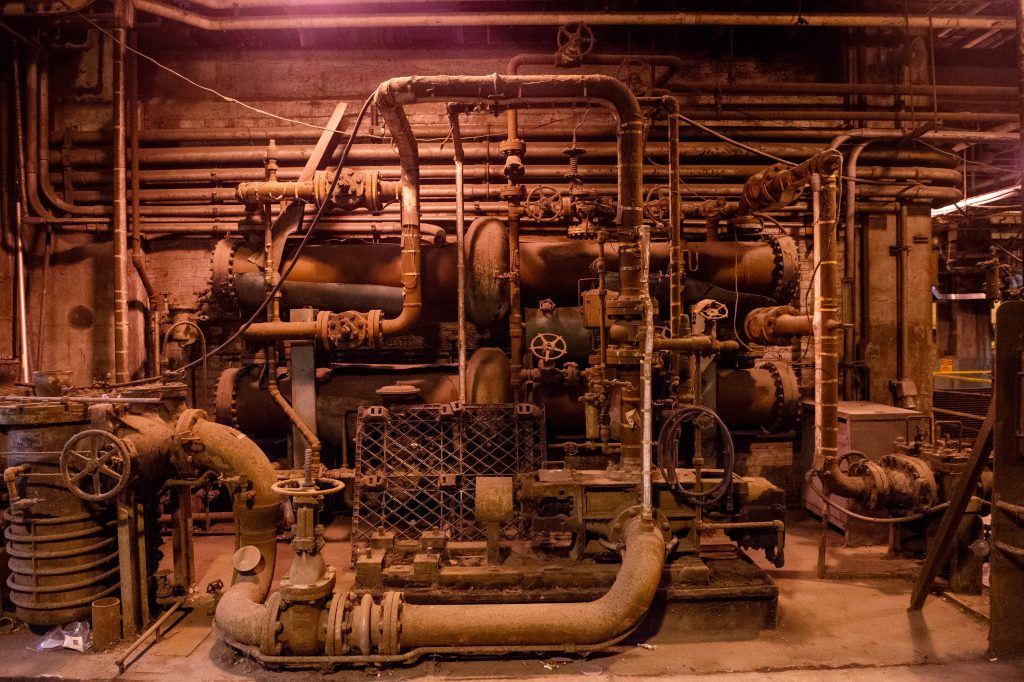

Ash and dust-covered mechanicals show their age in the power block facility where trash is converted to energy at the MIRA facility. Shredded trash is fed into combustion boilers providing steam for turbines that produce electricity. Photo credit: Cloe Poisson (Courtesy of CTMirror.org)

Recycling is in a worldwide crisis right now, however, as China, which does the bulk of the actual product recycling, has cut back, mainly due to pervasive contamination of the recycling stream. This means that instead of making a small amount of money on the purchase of their recycled materials, cities and towns are now paying a considerable amount to get rid of them.

Then there is the matter of food waste — or, more euphemistically, organics. In Connecticut, a small amount of commercially-generated organics is composted or turned into energy in the state’s one anaerobic digester. But food waste mainly winds up in trash-to-energy plants.

This is not ideal. Food waste is heavy, wet, doesn’t burn well, and there’s a heck of a lot of it. It’s widely agreed that getting organics out of that stream would go a long way towards dealing with the trash-to-energy capacity problem, especially at the MIRA plant.

It also begs the question of what a new MIRA plant should be.

The term sheet released in November, which includes a list of specifications for the project, would essentially rebuild what’s there, with the same size facility and same sorting process more modern plants in the state don’t use. It’s also expensive – more than $330 million to replace both the plant and the recycling operation also on the site. Without a state subsidy or bonding, the new facilities would cost towns nearly twice what they’re paying now to dump their trash and recycling.

Plus, the plant is looking for 30-year commitments from cities and towns, something that may keep them stuck with it even as newer technologies are proven to be more effective. A new facility may also eventually include an organics separation component, which raises the question of whether a smaller plant would do.

One of two General Electric steam turbines at the Hartford MIRA plant. The turbines, which date back to 1950, generate 45 megawatts of electricity. Photo credit: Cloe Poisson (Courtesy of CTMirror.org)

Sources indicate there is little appetite by state government to foot even a portion of a bill that size. And with the largely Balkanized system of trash disposal in Connecticut, there’s been little to no interest by lawmakers to contemplate statewide action that could take advantage of coordinated policies and economies of scale to modernize trash systems.

But a task force on recycling started by House Speaker Joe Aresimowicsz and discussions between lawmakers and the administration indicate some consideration is being given to starting that process in the upcoming legislative session, especially given the delicate condition of the MIRA plant and the prospect that it could shut down again – possibly for good.

Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin has long fought the MIRA plant or any continuation of it. That’s largely because of its location on prime riverfront land, though plant officials say remediation of the site for anything other than industrial use would be difficult and expensive.

But there’s a bigger issue, Bronin said.

“The question is are we going to double down on the strategies of the last generation or are we going to try to look at the issue of trash disposal statewide with fresh eyes and ask ourselves ‘What is the most fiscally sound, environmentally responsible way to dispose of our state’s trash and then where should we best do that?’” he said. “I would like us to not make the decision about what we do in the next two generations based on what we’ve done for the last two generations.”

Replacing the outdated MIRA plant would cost as much as $330 million. Photo credit: Cloe Poisson (Courtesy of CTMirror.org)

While new technologies are being developed to replace trash-to-energy, the widely shared view is they are not ready for prime time. MIRA CEO Kirk said the plan for the facility would allow it to adopt newer systems as they are available.

But what he and Peter Egan, MIRA’s director of operations and environmental affairs, would like most to see is a wholesale policy shift of responsibility for municipal solid waste from towns to the state.

“That would be step in the right direction,” Egan said.

“You won’t get many arguments from the first selectmen,” Kirk added.

DEEP Commissioner Katie Dykes said municipal customers are “in the driver’s seat,” when it comes to changing the trash system.

But are any of those municipalities actually doing any driving?

Optibag, organics and fortitude

Stonington’s Phetteplace is planning to do plenty of driving and bring the 12 member towns in the Southeastern Connecticut Regional Resources Recovery Authority – or SCRRRA (pronounced SKAH-rah) – with him.

Stonington started curbside textile pickup in the new year, and Phetteplace is now considering a 600-customer pilot project based on the European multi-colored bag system. That system typically uses these bags – more than half-a-dozen in some cases – to separate trash at homes, businesses, and even public locations for simple sorting at the processing site.

In the Swedish system known as Optibag, considered the gold standard for trash disposal, bags are picked up in one truck and then optically scanned and separated at the sorting facility through an entirely automated process.

In the Optibag system, waste is sorted in color-coded bags at home. Optibag photo (Courtesy of CTMirror.org)

Phetteplace wants to test a home-separation system similar to Optibag. It would have a recycle bin plus four bags – food, trash, hard to recycle plastics, and textiles. A hauler with a split-body truck would collect all five at once.

More broadly, the SCRRRA board, which Phetteplace leads right now, has authorized a feasibility study on food waste collection, including finding a site for composting it, which is much cheaper than burning it.

But perhaps most critically, SCRRRA has a new contract for waste disposal. After using the Preston facility since the mid-1980s, beginning in Jan. 2021 the authority will switch to the Lisbon trash-to-energy plant. But unlike the 30-year contracts the MIRA plant wants, this is only for 10 years – enough time, Phetteplace said, to figure out how to move into the future of trash collection.

Dave Aldridge, executive director of SCRRRA, said he’s considering using some of the authority’s funds to incentivize other towns in the region to try Stonington’s pay-as-you-throw system.

“From the political side, I can tell you at a municipal level, there’s no fortitude to go after it,” he said, using that word again. “It’s almost cost some of our CEOs their elections. The passion against it is just unbelievable.”

Jennifer Heaton-Jones is executive director of the Housatonic Resources Recovery Authority, which has 11 member towns in western Connecticut, all of which have private subscription services for waste and recycling hauling. An 18-month food waste pickup pilot project was a success in terms of use, but unsustainable financially for the hauler. Five of the 11 towns have food waste drop-off programs now. Redding, for one, charges 20 cents per pound to drop off trash, but only 10 cents per pound for food waste.

“Ultimately, what we’re talking about is behavior change,” she said, adding that talking about environmental impact and public education won’t do it. “It needs to be literally outreach, going door-to-door with incentives.”

But we’re also talking about money, said DEEP Commissioner Dykes.

“We have to be responsive to the reality that some individuals are going to be better able to afford those costs than others. That’s something that we have to be sensitive to in the design of unit-based pricing,” she said.

But, she conceded: “Cities, communities that have adopted PAYT – the statistics are mind-blowing.”

Public trash receptacles in Paris separate items in color-designated bags. The United States lags behind other nations when it comes to trash separation and disposal. Photo credit: Jan Ellen Spiegel, CTMirror.org

Worcester, Mass. is one of them. A moderate income city, Worcester adopted PAYT in the early 1990s; today, about half the cities and towns in Massachusetts use that system for trash disposal. Bob Fiore, assistant to the commissioner of Worcester’s department of public works, helped launch PAYT in the city but said he’s not sure it would have worked if social media had existed back then.

But, he said, city streets are clean and there’s 99.9% compliance.

“We’ve had so many communities coming through here over the 26 years and I’ll take them through the toughest neighborhood and I’ve never had anyone not say ‘Wow,’” Fiore said.

Dykes’ predecessor Rob Klee is a trash expert who, as DEEP commissioner from 2014 until last year, launched several innovative collection practices, including mattresses and paint. Klee is a fan of pay-as-you-throw and tells students he teaches at Yale that it amounts to putting a meter on your material footprint.

“When you are paying for it, you start making better choices,” Klee said. “You start thinking about diverting some streams out of your waste.”

He pointed to the Scandinavian systems, Optibag in particular. “They do a really good job of getting everything out of the front end,” he said. “You end up with a system that has very little residual that’s going to be incinerated. And that was the spirit of where we really wanted to head – to reduce reliance on waste-to-energy.”

Joshua Reno, an assistant professor of anthropology at Binghamton University who studies trash, said even before looking at how to handle the trash, “we should be thinking differently about how we consume.”

In a nation that equates economic prosperity with consumption, that’s not something people want to hear, he said.

“If that doesn’t change and if we don’t rethink how we think about economics and what we privilege in terms of policy orientation, then I think questions about the future of waste treatment are kind of secondary,” Reno said. “They’re all an outcome of that activity and we’re just trying to put a Band-Aid where a tourniquet is needed.”

Reprinted with permission of The Connecticut Mirror. The author can be reached at [email protected].

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!

Paper and plastic “recycling” has turned out to be little more than a hoax, with huge amounts of money spent on diesel barges to bring this stuff to 3rd world countries where much of it is just dumped. Even the small amount that gets recycled is often used to make inferior, contaminated goods. The goal should be to send all paper and plastic to trash-to-energy facilities and make them as clean burning and efficient as possible. The electricity should be offsetting the cost, since the power is reliable can can be increased during peak loads.