Op-Ed: The Twisted Steel of Ground Zero and How it has Defined the 9/11 Generation

Audio By Carbonatix

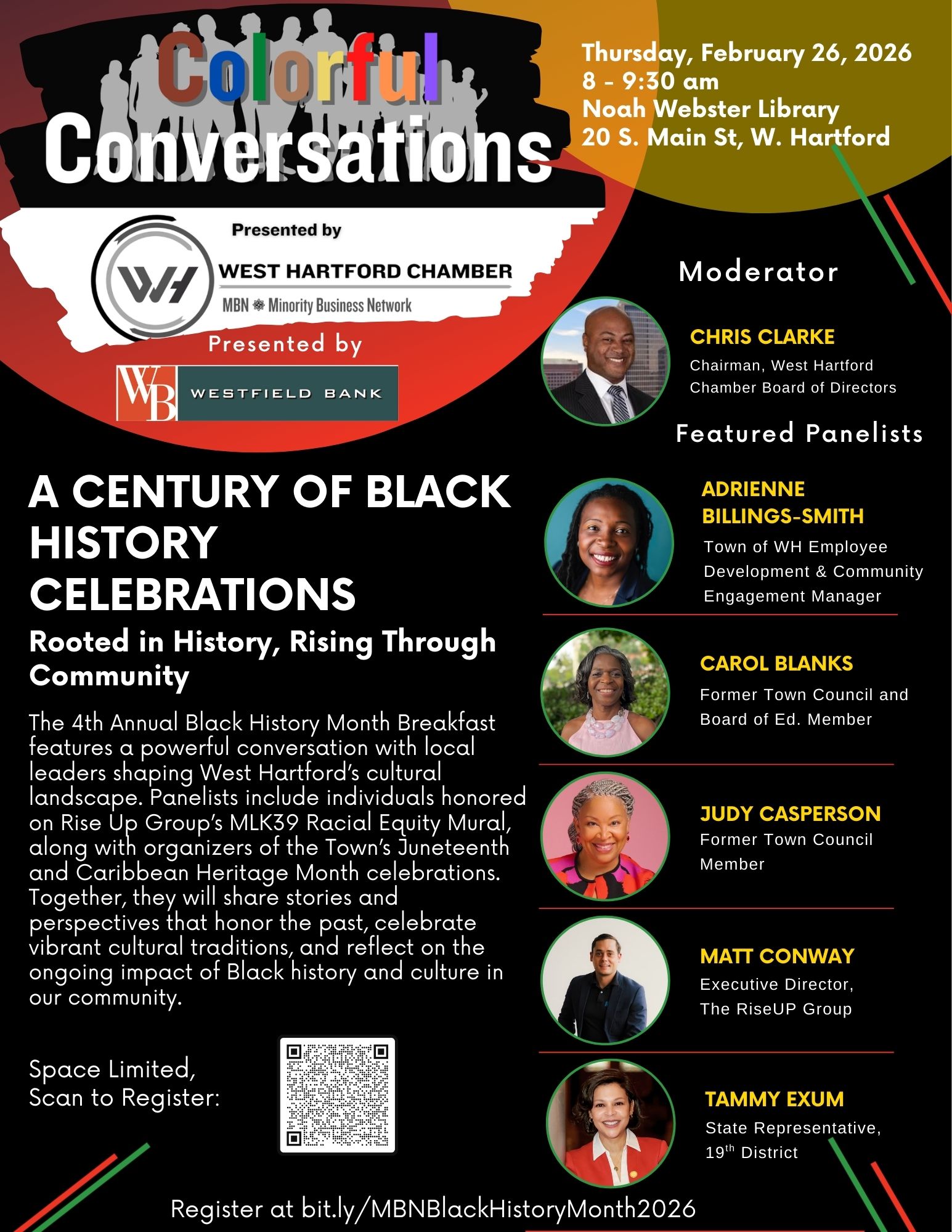

Matt Warshauer with Shemar Samuels on a 2018 trip to Ground Zero. Courtesy photo

As a college professor who is surrounded by 18- to 23-year-olds, Matt Warshauer has had a unique vantage point through them as 9/11 has morphed from tragedy to history, and continues to define an entire generation.

Matt Warshauer’s students on a trip to Ground Zero in 2019. Courtesy photo

By Professor Matt Warshauer, [email protected]

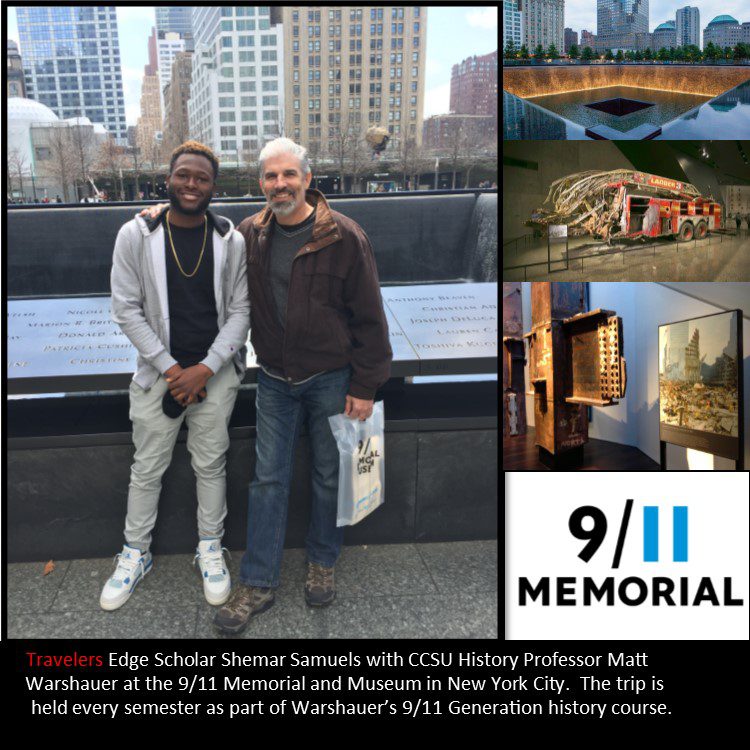

The remains of the ragged steel box columns mesmerize me. Saw cuts are still visible from the full day it took a clean-up worker to release just one of the mangled beams that moored the World Trade Center to the bedrock of lower Manhattan. Dozens of these now “artifacts” mark the perimeter of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, outlining what’s left of towers that continue to haunt America’s memory. They’re symbols of both an end and a beginning, fragments of a past that defines our children’s generation.

This is true even though many in the 9/11 Generation don’t remember September 11 and wouldn’t readily feel the power of the box column remnants. Isabella, only 10 months old when the attacks came, says, “when 9/11 shook America to its knees, I was playing with my blocks in my grandma’s house, safely and blissfully unaware as she and my grandpa hugged and cried at the images of the World Trade Center burn and crumble.”

Tori wasn’t even born yet. Her mother was 8 months pregnant and stuck in a New York subway trying to get to a meeting in the South Tower. She never understood why the hijackers got onto the planes that day but knows they traumatized her childhood. “My mom spoke of times before the attacks, that she would leave the house for work in NYC. She never hugged my father goodbye, never talked to him during the day, never was afraid of death, and wanted many kids.” Then everything changed. “After September 11th, she never left the house without hugging everyone, all she did was stare at her phone making sure her family was safe, lived in fear every day, and never wanted to bring another child into this dangerous world.” Like so many in her generation, Tori grew up in the turbulence of 9/11 fear.

Remnants of the World Trade Center’s steel columns. Courtesy of Matt Warshauer

These are the voices of my students, just two among hundreds who have spent a semester over the years exploring the many meanings of September 11 and how it impacted their lives in known and unknown ways. As a college professor, I’ve held a unique vantage point, each year surrounded by 18- to 23-year-olds as 9/11 has morphed from tragedy to history. I’ve watched this generation develop, listened to their worries, and spent countless hours exploring the depth of how that stunning Tuesday morning in September shaped America and, inevitably, their lives.

Unlike those who grew up in the long wake of 9/11 chaos, the children old enough to see what was happening that day felt the fear crash down all around them. Emma Lord wrote about “What It Was Like to Be Ten Years Old on 9/11,” explaining, “We are all of us united by the sharp moments that never faded – watching our parents cry in front of the television. Watching our teachers abandon their lesson plans. Watching kids get pulled out of school.” She remembers, “We were children. Watching was all we could do.” There was a sense of helplessness and a disbelieving belief that it was all too real.

For Lord and other kids in the midst of adolescence, the attacks and post-9/11 world was everything. “I had no concept of what the world was like,” she wrote. “September 11th didn’t change the world for me – it defined it.”

The 9/11 Generation was born. They aren’t Gen Z, a concept that’s barely definable except that it comes after Gen X. No, the kids who watched those towers fall over and over again on television were inescapably forged by the fires of September 11. Our children are the box column remnants of the World Trade Center; they’re astoundingly real and viscerally symbolic.

Adults were shocked and barely able to process what was happening to the mighty United States. We expressed our grief through a tapestry of American flags that fluttered from sea to sea. We held our children more tightly.

They were the first thought for parents in the midst of the 9/11 panic. Moms and dads rushed to the nation’s schools and hurried their children home in an instinctual need to protect. That bizarre school day, when everything stopped, is one of the single most shared cultural experiences of any generation.

Our teachers witnessed it first-hand. Jillian Baden Bershtein taught third grade in Trenton, New Jersey. She remembers that “the day went by in slow motion,” frantic parents arrived to snatch their children home, and “despite the kids’ curiosity, we were not to discuss the happenings, but we were instructed to assure them that everything was OK.” The unnerving quiet was broken by an innocent, but alarming question from an 8-year-old: “Are we gonna die?”

Jensen Rodriquez, a kindergartener from Connecticut, was in the school cafeteria. “I took only one bite of my dinosaur chicken nuggets before the librarian grabbed me by my arm, told me to grab my backpack and took me to the office in the third level of the building where my mom was waiting with her eyes in tears.” Jensen went home to chaos. The television was on and the second plane, caught in a never-ending loop of destruction, slammed into the South Tower again and again. Both towers were billowing smoke, Jensen’s grandmother was “screaming in despair in the living room,” and aunts and cousins descended on the house. Everyone was in shock.

For the next many months and years, as America feared another attack, cleared out the wreckage of the twisted steel at Ground Zero, fought wars on two fronts in the Middle East, and struggled to recover from an economy that had crashed with the towers, the 9/11 Generation continued to breath in the stress and fragile emotion of a post-September 11 America.

When Seal Team Six finally hunted down and killed Osama bin Laden, the 9/11 Generation surfaced on the streets of America to celebrate the death a man who had haunted their dreams. He was their boogeyman, the monster under the bed. The night that President Obama announced bin Laden’s death the first person I heard from was my nephew, Alexander, a student at Boston College. It was a simple text: “Did you hear? We got him! Bin Laden.” The news showed reveling college-age students across the country waving American flags, chanting U-S-A, and partying.

It was a sobering moment. Not because the death of bin Laden changed anything concerning the War on Terror, but because that sea of young people in the streets were 8 and 10 years old on September 11, 2001. They were Emma Lord and all the other children who remembered. They were my students. For a brief moment, the 9/11 Generation savored victory over a man who had tormented their childhood and unleashed the disturbing reality of what the world could really be like. That was his intention.

But bin Laden’s death was a hollow victory. Nothing changed. The War on Terror continued; the disfunction never abated. The recent events in Afghanistan, the fall of Kabul and the rush to withdraw as many people as possible, speak directly to the continuing effects of September 11.

If a single word sums up the experience of the 9/11 Generation, it’s “chaos.” They’ve never known a time without war, economic challenge, and violence – whether it comes from the threat of foreign terrorists or the gun barrel of a classmate. They’ve never known functional government, a democratic system that confronts and solves national problems.

In this, the 9/11 Generation is undeniably unique. They’ve seen no answer to a Great Depression, no end of a Vietnam War, no ousting of a president who defied the law. Instead, they’re witnesses to an erosion of democratic values, the contested meaning of voting, and a maddening inability of the nation’s leaders to solve the critical issues that threaten their world: gun violence, climate change, their economic future.

My student Alexandra, only 3 during the attacks, defines the circumstances of her generation with clarity. “I wish I had a memory of a world before 9/11, before the war in Iraq, before the systematic racism and fear towards Muslims, before a generation with anxiety levels equivalent to mental patients in the 60s.” She continued, “the 9/11 generation consists largely of people who have no personal narrative of the event that has shaped nearly every aspect of their lives. We are a generation drowning in anxiety, debt, and financial insecurity.”

And then came COVID, arriving just as the tail end of the 9/11 Generation reached college age. Many see the government’s pandemic response as yet another failure. “As the War on Terror reaches its 20-year mark and continues to be scrutinized in the public,” wrote Molly, “a new disaster has fallen upon the U.S. to be mishandled by its government, COVID-19. The little trust the 9/11 Generation had in its government prior to 2020, is quickly vanishing.”

This lack of faith has become endemic in the 9/11 Generation. Like the twisted steel of the trade center, the supporting structure of their morale and sense of wellbeing has been shaken to its core, as has their trust in the system. “It wasn’t a day that was ruined. It was a whole week, a whole year, a whole generation,” insists Sheelan. You can try to separate America from 9/11, but it can no longer be written without that event, because America is no longer America, but 9/11’s America. 9/11 owns us, m*****f*****s.”

This is the reality of so many in the 9/11 Generation. There exists an angst and anger that even they can’t easily explain. Some don’t recognize it as initiating primarily from 9/11, but it’s there, nonetheless. In the weeks and months after the attacks, some insisted that the United States had lost its innocence, others wrote that the nation had been expelled from Disneyland, an almost beatific make-believe world in which dangers from abroad didn’t exist.

This is one of the key differences between the before and after of 9/11. It rests on the dividing line of hope and belief, of faith in leaders and democracy.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, President George W. Bush famously announced that “terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings, but they cannot touch the foundation of America. These acts shatter steel, but they cannot dent the steel of American resolve.”

He was wrong. The distressed steel of America is found in those ragged box columns at the September 11 Memorial & Museum, and in our children – those who grew up in the shadow of towers that no longer exist.

Matt Warshauer’s students on a trip to Ground Zero in 2018. Courtesy photo

West Hartford resident Matt Warshauer is a professor at Central Connecticut State University, a political historian, and the author of a soon-to-be published book about the “9/11 Generation.” He is also well known for the Halloween displays he creates in front of his North Main Street home.

We-Ha.com will accept Op-Ed submissions from members of the community. The views, opinions, positions, or strategies expressed by the author are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or positions of We-Ha.com. We reserve the right to edit all submitted content.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.