Task Force Looks to Minimize Police Interaction with Mentally Ill

Audio By Carbonatix

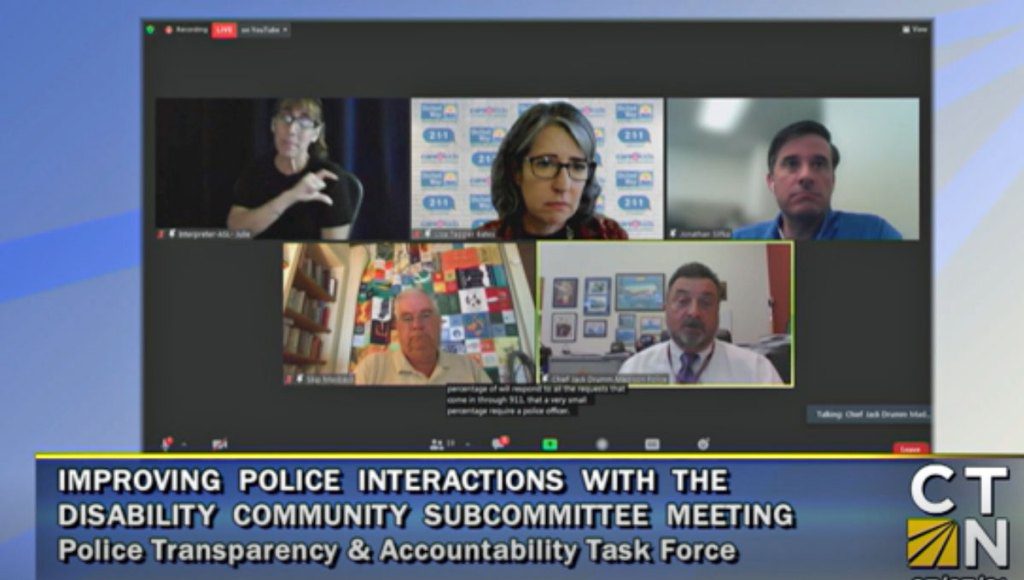

Police Accountability Subcommittee (Courtesy of CT-N)

One element of increased training would educate officers on how to recognize a person who has a disability that may be inhibiting them from communicating, said Jonathan Slifka, who represents the disability community on the task force.

By Lisa Backus, CTNewsJunkie.com

Fatal police shootings involving a person with a known mental illness in Connecticut occur significantly more than than the national average, according to data presented to the state’s Police Transparency and Accountability Task Force.

A 2015 report issued by Virginia’s Treatment Advocacy Center Office of Research & Public Affairs found at least 23% of fatal police shootings involved a person with mental illness. Skip Masback, a Connecticut Bar Association member reporting for the group’s data subcommittee, told the task force that in Connecticut the number is closer to 40%. The information was part of a presentation on “Reimagining Police” last month.

“I was surprised it was that high,” said Jonathan Slifka, who represents the disability community on the task force and chairs the subcommittee on improving police interactions with that group. “I guess that’s because with the racial issues going on across the country and in Connecticut you don’t read about it much. You just don’t hear about it as much as we should.”

Slifka and the subcommittee are on the verge of voting on recommendations addressing how police would respond – or not respond – to people with disabilities who are in crisis. Recommendations approved by the subcommittee would move to the entire task force for approval and inclusion in a report to the legislature.

The goal is to reduce negative interactions – including fatal police shootings – through training and other awareness measures that provide alternatives to police involvement with people who are having a mental health crisis.

Increased training would educate officers on how to recognize a person who has a disability that may be inhibiting them from communicating, Slifka said. “If you are dealing with someone who is non-verbal or they don’t give you eye contact, those are behaviors that are associated with a disability,” he said. “If an officer is trained in recognizing that, it would go a long way in minimizing negative or tragic outcomes.”

Other recommendations include training 911 dispatchers on how to properly allocate resources to a call for a person in crisis that doesn’t necessarily require the presence of armed police officers, and an awareness campaign for the public on when to call 211 to seek mental health services versus when to call 911.

In 2020, 211 received 120,000 crisis calls but only 1% were escalated to 911 calls, according to Lisa Tepper Bates, executive director of the United Way of Connecticut which runs the 211 system. “What that tells us is that the separate crisis response works,” Tepper Bates said during the July subcommittee meeting.

What hasn’t been tallied is how many 911 calls were made that could have been addressed with crisis services from 211, she said. “How do we build awareness that there is an alternative to 911?” Tepper Bates said.

The recommendations also advocate for the expansion of mobile crisis intervention teams in municipalities throughout the state and the hiring of social workers to work with police during calls for persons experiencing a mental health crisis.

Municipalities can take budgetary factors into consideration when developing plans to get some of the recommendations accomplished, members of the subcommittee noted in a draft that will be voted on during their next meeting on Aug. 31.

Madison Police Chief John “Jack” Drumm is on the task force and said Tuesday that he thinks he has the answer for his department. He’s in talks with area universities to partner with social work and psychology students who would be paid a stipend to be available for shifts working with officers on calls for people in crisis.

In years past, a person who was having a crisis would be sent by ambulance to the hospital, Drumm said. Now there’s a movement toward less force, more discussion and a follow-up with services, he said.

He’s hoping to have the university student plan in place by January, he said. He thinks that it will work for small or medium towns such as Madison, Drumm said. But he said larger cities with a higher call volume for dealing with disturbed persons will likely have to hire social workers full time.

“What I’d like to see is three or four models for the whole state,” Drumm said. “What’s the model for cities of 100,000? What’s the model for towns with 25,000?”

Under his plan, the university where the students attend would provide clinical oversight. Ideally the students would offer follow-up services to the people in crisis they helped during the original call, Drumm said. The initiative would bring Madison into compliance with 2020 police accountability law which calls for every department to study the feasibility of utilizing social workers or crisis intervention teams, he said.

But it would also provide people in crisis a more sensitive approach when help arrives, he said. “Usually when two officers get out of the car, they are armed and they are wearing a uniform,” Drumm said. “For some people that’s not the way to start a conversation.”

In New Haven, Mayor Justin Elicker is helping to create a Community Crisis Response Team to send social workers and mental health workers instead of uniformed officers to some emergency calls for help.

The Elicker administration is halfway through its six-month planning phase to create such a team. It is partnering with Community Mental Health Center (CMHC), which already does emergency crisis response, to oversee this planning phase and figure out whom to send on which 911 calls.

Republished with permission from CTNewsJunkie.com, all rights reserved.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.