Transgender Sports Debate Polarizes Women’s Advocates

Audio By Carbonatix

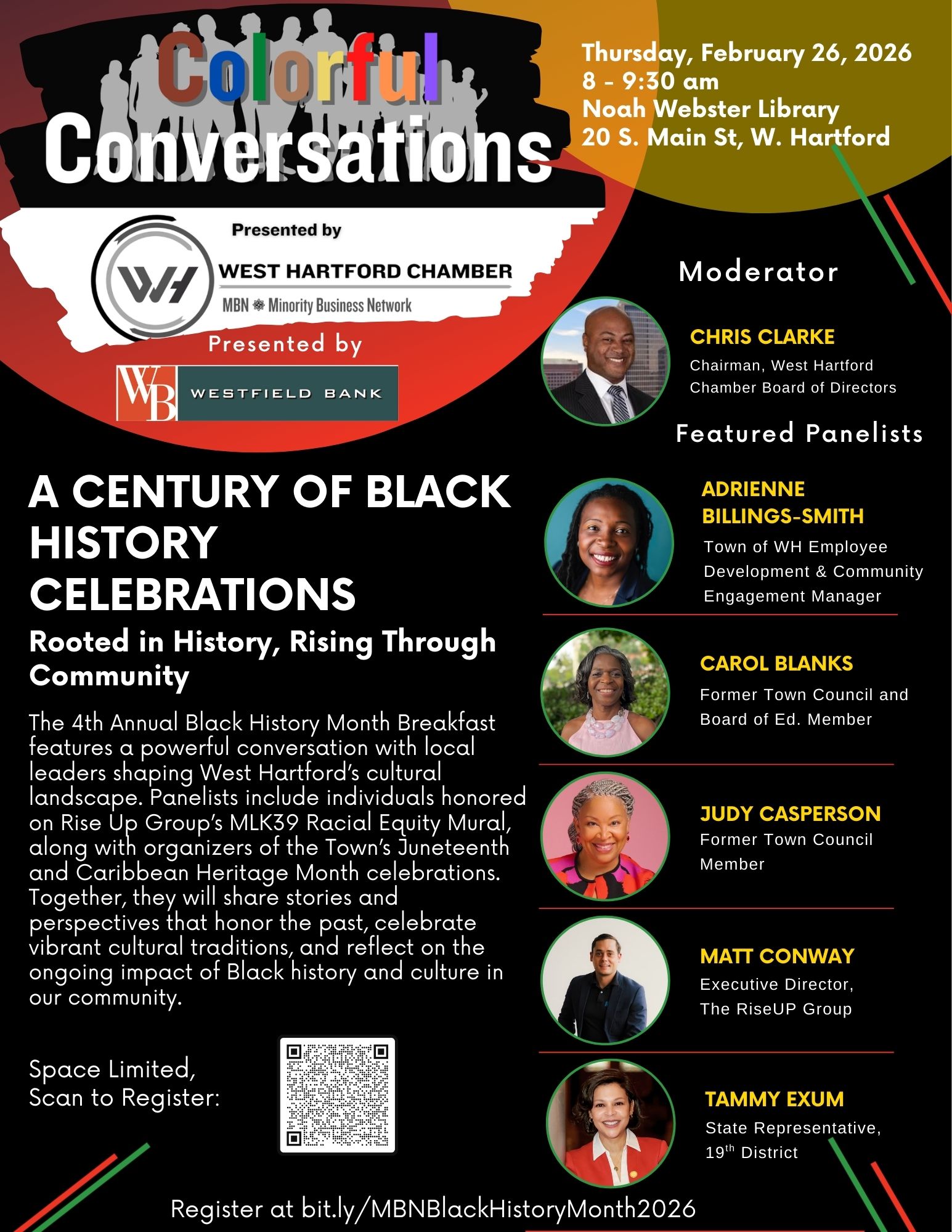

Terry Miller breezed to a first place finish in the 100 meter dash with a time of 11.77 seconds during the State Class M outdoor high school boys and girls track and field championship at Veterans Memorial Stadium in New Britain in May, 2018. Andraya Yearwood (L) of Cromwell placed 2nd and Nikki Xiarhos (R) of Berlin placed 3rd. (Photo credit: John Woike/Hartford Courtant. Courtesy of CTMirror.org, file photo)

Coaches and advocates, including several from West Hartford, weigh in on the issue after Glastonbury High School runner and two other girls filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights arguing that their rights under Title IX have been violated by the CIAC’s policy for transgender athletes.

By Kathleen Megan, CTMirror.org

Before every race she enters, Selina Soule follows the same routine. She wakes up early and applies her signature meet make up – royal blue eyeliner to match her Glastonbury track uniform.

Selina Soule, one of three female runners who have brought a Title IX complaint against the state. Courtesy of CTMirror.org

She struggles to choke down half of the egg sandwich her dad makes her, and then she listens to a “pump playlist” that includes the song “Win the Race” by Modern Talking to help get her into the zone.

“Just like my fellow competitors, I race to win,” she said. “But that’s virtually impossible now in an unlevel playing field.”

Soule, a Glastonbury High School junior, believes the Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference (CIAC) policy that allows transgender girls to compete in girls’ sports without any hormone treatment is unfair.

That sense of injustice is at the heart of the complaint Soule and two other girls filed with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights in June arguing that their Title IX rights have been violated by a policy that they say pits girls against athletes who are biologically male despite their female gender identity. They contend the situation has robbed them of top finishes and possibly college scholarships.

With the CIAC policy in play, Andraya Yearwood of Cromwell and Terry Miller of Bloomfield – transgender girls who are track and field athletes – have grabbed national headlines and multiple championships, with Miller shattering state records in recent years and winning the Hartford Courant’s girls’ indoor track and field athlete of the year award in 2019. Both athletes also won the state’s sportswriters’ “courage award.”

Experts in girls’ sports and Title IX, the federal law that requires that women have equal access to sports, believe Soule and other cisgender athletes could have a valid complaint. They point out that both the NCAA and the Olympic Committee require transgender women to receive hormone treatment for at least a year and be tested for testosterone levels. The CIAC does not require either.

Donna Lopiano. Sports Management Resources. Courtesy of CTMirror.org

“I don’t know of a woman athlete who doesn’t want trans girls to be treated fairly,” said Donna Lopiano, who led the Women’s Sports Foundation for 15 years and now runs a Shelton-based consulting firm that works with clients on Title IX and other sports management issues. “But the cost of treating her fairly should not come at the cost of discriminating against a biologically-female-at birth woman.”

Lopiano is hardly alone. The controversy over the inclusion of transgender athletes on girls’ high school teams in Connecticut has deeply divided advocates who are usually in agreement when it comes to female sports, including lawyers, women’s group leaders, athletes, and parents.

“It’s amazing how polarized people get. Connecticut could be on the forefront of creating a structure or some way that lets both transgender and cisgender females fully participate, so that they both can be protected,” said Felice Duffy, a former federal prosecutor with a law practice in New Haven that focuses on Title IX. “There’s good people who will be very willing to talk about it and do it in way that makes sense.”

It’s a rift that has been driven even deeper by the involvement of the Alliance Defending Freedom, the group that filed the Title IX complaint on behalf of Soule and two other female athletes. The ADF has opposed allowing transgender girls in traditional girls-only spaces, including bathrooms and locker rooms.

But Doriane Coleman, a Duke University Law professor who has worked on the issue of sex in sport and has consulted with the National Scholastic Athletic Foundation, said ADF’s participation shouldn’t turn a non-partisan issue into a partisan one.

“This isn’t bathrooms. Sports are different,” Coleman said. “It’s wrong to think of the OCR complaint as reflecting a right wing or conservative Christian position. It’s not. People across the political spectrum care about ensuring that girls and women have an equal chance at the goods that flow from sport. The sports exception in Title IX, which allows schools to have separate teams for males and females, is about creating and protecting the space where this can happen.”

For now, however, the sides are very far apart.

Recently, 16 Connecticut women’s rights and gender justice groups – including NARAL Pro-Choice Connecticut, the New Haven Pride Center, and Planned Parenthood of Southern New England – signed a statement supporting “the full inclusion of transgender people in athletics.”

“Transgender girls are girls and transgender women are women,” the statement said. “They are not and should not be referred to as boys or men, biological or otherwise.”

“We speak from expertise when we say that nondiscrimination protections for transgender people – including women and girls who are transgender – advance women’s equality and well-being.”

Changing the definition of gender

Title IX was passed 47 years ago to ensure an equal education for girls, but included a “carve out” allowing separate sports programs for girls because of the clear biological advantage that males have over females in athletics.

“It was the notion that there are distinct biological differences in sex that are immutable,” Lopiano said, “namely after puberty, the effect of testosterone on males … Everybody agreed that hey, if you have boys and girls competing after puberty, who would be more likely to get on a team? Who would win? It would be men. There would be very few women.”

The current CIAC policy was developed in the context of federal and state law. A state law passed in 2011 prohibits discrimination based on sex or gender identity and does not require that a person’s gender be determined by that individual’s sex at birth, nor does it require a person to have undergone hormone therapy to be identified as a gender different from that assigned at birth.

The way Lopiano sees it, Connecticut’s law says, “Hey, we are going to change the definition of sex,” she said. “Now a woman is someone who identifies as woman, not someone who is biologically a woman… I’m not trying to criticize the definition, but that’s in effect what the law is saying.”

In a state that requires high schools to allow transgender girls to play sports with girls even if they have not had hormone therapy, Lopiano said, the challenge is how to do that fairly.

“I think you can do it, but not without an accommodation for their advantage,” Lopiano said.

Duffy says she believes the way state law is being applied violates Title IX because it only disadvantages cisgender females.

“It’s been shown that transgendered females who were assigned male at birth have the potential to be superior in power, speed, and strength in sports, such as track, based on hormonal levels and other things,” Duffy said. “And I would say to the converse, transgendered males assigned female at birth don’t have the potential to be superior to males in track and field, for example. And therefore, there’s no negative impact on cisgender males.”

She said the NCAA and IOC rules further reflect this because they require transgender females to undergo hormone therapy to reduce their physical advantages.

“No one in Connecticut wants to discriminate against transgender girls, but by giving them the full go-ahead to participate you, in effect, are discriminating against cisgender girls from my perspective,” Duffy said, adding that the inequity is particularly clear when it comes to post-season competition.

That was Selina Soule’s experience.

Only a limited number of high school runners are allowed to advance to the state finals and Soule missed that chance in February when she came in eighth at the 2019 State Indoor Open in the preliminary 55-meter race. Only the top seven finishers were allowed to move on to the finals. Miller and Yearwood, the two transgender girls, occupied the two top slots.

“I respect these transgender athletes, and I understand that they are just following CIAC policy. But at the same time, it is demoralizing and frustrating for me and for other girls,” Selina said in a recent email. “No matter how hard I try, I’ll never be able to be competitive with someone who’s biologically a male … No amount of practice and determination will ever get me or other girls to a place where we will have a fair chance to win. But the CIAC doesn’t seem to care.”

Her mother, Bianca Stanescu, said she has been surprised by the lack of support for her daughter and the other cisgender athletes.

“It’s especially surprising and sad to see that most women’s groups in Connecticut have lined up against fairness for girls,” Stanescu said. “Why aren’t they speaking up when girls are getting pushed to the sidelines and denied equal opportunities? Why aren’t they seriously looking at the scientific and legal issues?”

Glen Lungarini, executive director of the CIAC, said that when he consulted with the U.S. Department of Civil Rights – months before the June complaint was filed – he was told that Title IX refers to sex but does not define what sex or gender is. “It reverts to your local legislature in terms of defining [sex and gender],” he said.

And he said, the state law is clear that a transgender girl should be treated as a girl. “They’re not transgender, they are female,” Lungarini said.

A statement from the CIAC said it will “cooperate fully if OCR decides to investigate this complaint. We take such matters seriously, and we believe that the current CIAC policy is appropriate under both Connecticut law and Title IX.”

The policies on transgender high school athletes vary greatly across the country with some requiring birth certificates to prove their biological gender, while others require hormone therapy for transgender girls. Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have policies like Connecticut’s that allow transgender athletes to compete in athletics with the gender they assert, without medical interventions, according to the Gay Lesbian & Straight Education Network.

“This isn’t rocket science,” Lopiano said. “I think there is a failure on the part of the CIAC to really think hard about how they can make a [fair sport structure] for both females at birth and those who self-identify as trans-girls, who choose not to alter their bodies. I don’t have the answers but I know there are answers. There’s not just one way to do this.”

If a situation like the one that prevented Soule from going to postseason competition arises, extra slots for cisgender girls could be added, Lopiano said, to ensure that cisgender girls get to fully participate along with transgender girls. Or, she suggested, there could be classes for girls during post season competition as there are for wrestlers of different weights.

Coleman, the Duke University Law professor, said the Connecticut girls’ Title IX complaint has finally brought a thorny issue to the fore.

“You wouldn’t have called and asked me about this last year because it wasn’t politically correct even to have the conversation,” she said. “The cisgirls and their families and people who are aligned with their interests have really not had the space to speak because whenever they’ve tried, they’ve been attacked for being bad people. They are not bad people. They represent the traditional view of what Title IX is all about.”

Coleman said she sees the complaint as viable particularly because the Trump administration has withdrawn the Obama administration’s transgender friendly “guidance,” and has made clear its preference for traditional definitions – specifically that “sex means sex, it doesn’t mean gender identity.

“It also happens that the majority of Americans, Democrats and Republicans, probably agree with them on this and that’s dangerous for Democrats,” she said. “I hope that liberal policymakers don’t cede this issue to conservatives. You can believe, as I do, that equality for people who are transgender is important and that we need to find ways to make that a reality, while also acknowledging that it’s a real leap to say that sex and gender identity are the same thing or that it’s harmless to pretend that they are.”

When civil rights trump fairness

Kate Farrar. Courtesy of CTMirror.org

For some advocates, however, allowing accommodations is tantamount to saying a transgender girl is not really a girl.

Kate Farrar, executive director of the Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Fund, said she doesn’t see how a distinction can be made between the regular season and the post season “if we’re working from a framework of equal access.”

“The fundamental issues behind Title IX and a lot of our gender equity fights are in recognition of [the need for] equal access,” Farrar added. “When we actually acknowledge transgender girls as girls according to their gender identity, we cannot deny them access. This is the whole point of why we have Title IX. Why we fought for gender equity.”

“It really is a human rights issue at the heart of these opportunities for girls in our schools.”

Dan Barrett, legal director of the ACLU of Connecticut, which has worked with the transgender girls, said the only question at issue in the complaint is whether Title IX permits the CIAC to adopt the policy it did.

“It’s not whether there’s a mandate to dream up something else,” he said. Rather, he said it’s whether the CIAC’s policy is permissible under Title IX.

Asked about taking steps to accommodate cisgender girls, such as adding slots for cisgender girls in postseason competition or creating classes for women’s sports, Barrett said, “that’s not equal treatment and that’s not going to fly in athletics.”

Making such accommodations “seeks to get behind the person’s gender identity,” Barrett said, “and say whoever it may be, the athletic conference or school … has decided that even though you’re living your life as a woman and that’s how you identify, we’re going to mark you off as something different and place you somewhere else.”

“In this case, it’s pretty straightforward: These women were competing as women and that’s the ballgame.”

Barrett also compared the advantage transgender females have to the advantages that superior athletes of the same biological gender have in competition.

“I swam in high school. I was captain of the swim team …” Barrett said, “but put me against Michael Phelps and it would not have been a contest. He was born with just an unbelievable wingspan.”

Advantages in sports are not just limited to physical prowess or skill, he added, because some students have wealthy parents who pay for private coaching, strength training, or summer camps.

“No one is clamoring for a special league for those athletes,” he said. “To do that to trans-athletes is not a particularly well disguised way of trying to discredit their choices, their autonomy as trans people.”

High school coaches offer differing views of how the issue is playing out on the track.

Betty Remigino-Knapp, who coaches girls track and field at Hall High School in West Hartford and a former athletic director in the town, said her cisgender runners have sometimes felt demoralized after competing against transgender girls.

When one of her sprinters was “knocked out of the finals” by a transgender runner last year, Remigino-Knapp said, “she just walked away, pretty discouraged, wondering what the heck just happened.”

“I have empathy for all kids … but in regard to athletics, you know, we’ve always been given a fair and level playing field,” said Remigino-Knapp, also a former track and cross country coach at UConn. “The physiological differences that males have over females – that’s why we have female sports and male sports. Otherwise, we could really save the CIAC a lot of money and just have one coed championship.”

Brian Calhoun, one of Yearwood’s coaches at Cromwell High School, said there have been no conflicts since Yearwood joined the team, noting that one of Title IX’s purposes, as he sees it, is to create athletic opportunities for a marginalized group.

“At first glance some people think the situation is unfair, but as you look at it, my overarching goals in athletics are to teach life skills and to help teenage athletes gather the skills that they’ll need later on in life,” he said. “If your goal is to teach our kids and prepare them for adulthood and you remember that’s your goal, it really becomes a much more clear issue.”

Both Terry Miller and Andraya Yearwood declined to comment for this story, but Rashaan Yearwood, Andraya’s father, said he is not interested in “debating the biological features of men and women.”

“This is only about my daughter being able to do what she wants to do. I don’t really care about the athletic angle at all,” Yearwood said. “Whether she wins or loses, she still would be running track. There have been plenty of cisgender girls who have beaten Andraya that have proven that Andraya being born male does not give her absolute dominance over the sport.”

Robin McHaelen, executive director of True Colors, a non-profit group that advocates for LGBTQ youth, said that while she understands the issue of fairness raised by the cisgender girls, she ultimately sides with the transgender athletes, who “have already experienced so much oppression and hostility.

“The honest to God truth is I don’t know what’s fair, but I know that my role is to protect and care for the most marginalized of the kids we serve and I think that transgender girls, especially girls of color, fit that category,” McHaelen said. “The reality is when you are talking about a civil rights issue, one person’s discomfort does not override another person’s civil rights.”

Reprinted with permission of The Connecticut Mirror. The author can be reached at [email protected].

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!