USJ Program Celebrates 100th Anniversary of Women’s Suffrage

Audio By Carbonatix

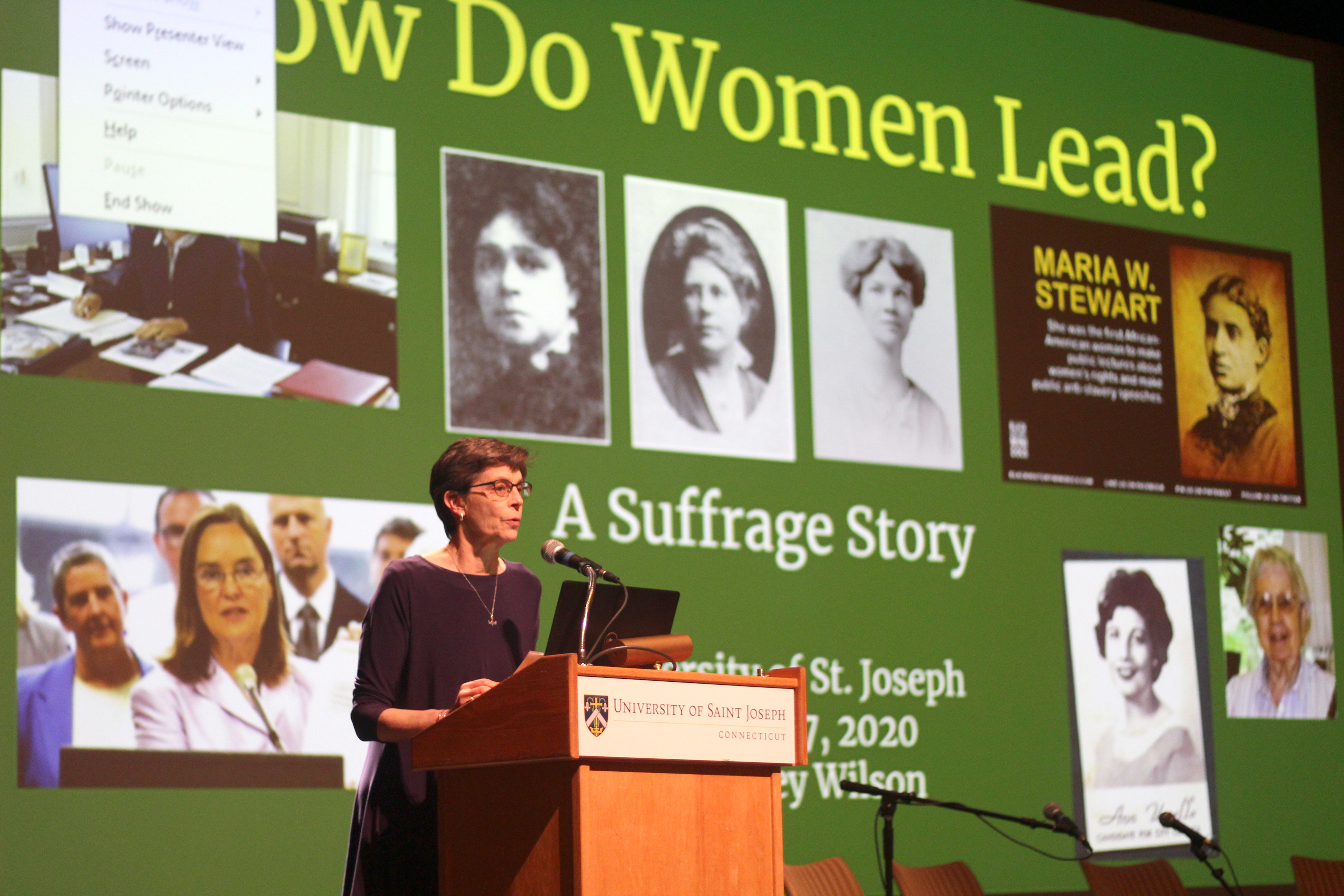

West Hartford town historian Tracey Wilson presented “How Do Women Lead?” an overview of some of the well known and lesser know figures in the suffrage movement. Photo credit: John Fitts (we-ha.com file photo)

A panel discussion at the University of Saint Joseph in West Hartford, that included Secretary of State Denise Merrill and historian Tracey Wilson, explored the complicated history of voting rights in the state and the U.S.

Participating in a post-speaker panel are from left, Secretary of State Denise Merill; USJ undergraduate and Obama Leadership Corps member Aya Cruz, moderator Molly Griffin, who is assistant director, government affairs for The Hartford, a sponsor of the program;

Brittney Yancy, Assistant professor of the Humanities, Goodwin College and West Hartford Town Historian Tracey Wilson. Photo credit: John Fitts

By John Fitts

While a recent program at the University of Saint Joseph celebrated the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, a roster of experts noted that the history of voting rights is a complicated one.

“What we really talking about here is the push and pull of history around voting rights in this county,” Denise Merrill, Connecticut’s Secretary of State, said at a Jan. 27 program on Voices of Women in CT Leadership: A Celebration of the Centennial Anniversary of Women’s Suffrage. “It’s all been incredibly tangled up with race and class and all kinds of things.”

Women, at least some of them, secured the right to vote on Aug. 18, 1920, when Tennessee became the last state needed to ratify the 19th, or “Susan B. Anthony” Amendment, passed on June 4, 1919.

But the historic victory did not end racial discrimination and other barriers many would-be voters experienced.

“The actual right to vote for millions of people, African Americans in particular, but also Native Americans, lots of groups, were not really actualized as voters until the voting rights act of 1965,” Merrill said.

And even before 1920, the effort was a long one, with just as many complexities.

While the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association was founded by Isabella Beecher Hooker in 1869, speakers noted that the movement actually began much earlier.

“The Connecticut Women’s Suffrage movement begin as formal organization in 1869 though people had been talking about women’s right way before that,” said Tracey Wilson, West Hartford town historian, who presented “How Do Women Lead,” a brief overview of suffrage history in the state and around the country.

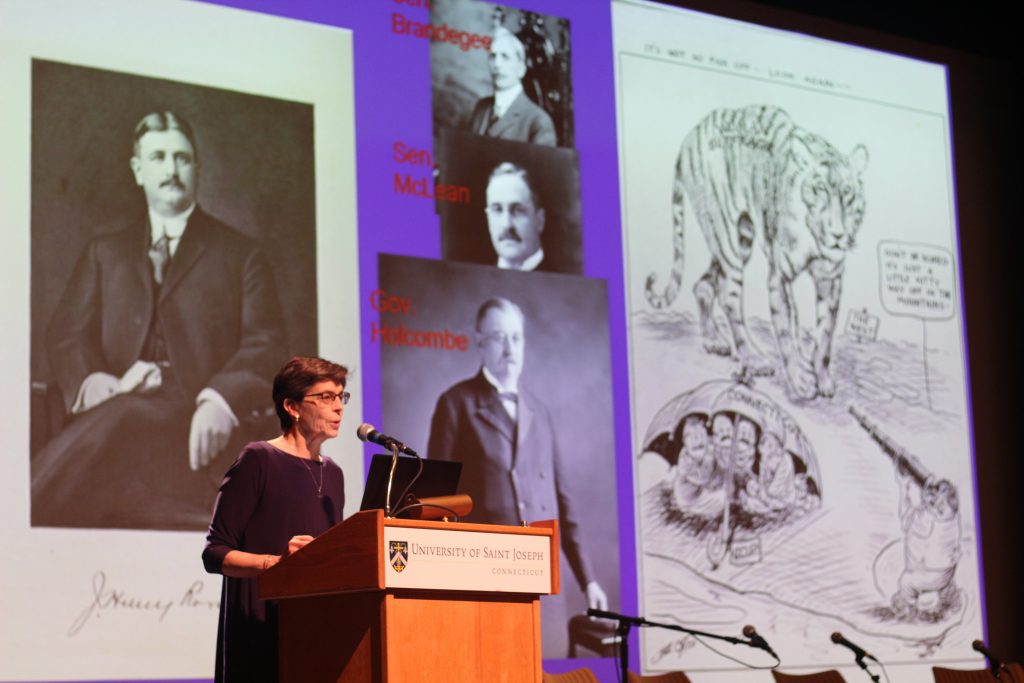

West Hartford town historian Tracey Wilson stands in front of a newspaper cartoon that mocked the resistance to women’s suffrage of prominent Connecticut politicians. Photo credit: John Fitts

Two years earlier, Frances Ellen Burr had petitioned enough signatures for the state to take up the issue of women’s suffrage, with the state legislature defeating it 111 to 93.

And as early as 1832, Maria Miller W. Stewart, born in Hartford, was speaking publicly about the issue, primarily in Boston, something rare for an African American woman of the time.

There were other early organizers in Connecticut as well, but it wasn’t until circa 1910 that the movement really moved more into the public spotlight, Wilson noted.

Wilson talked about some of the well-known leaders in the movement, such as Josephine Bennett and Katharine Houghton Hepburn, who were initially key players in the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association, which pushed a conservative, state-by-state approach, but later joined the National Women’s Party, which was in favor of more radical techniques such as getting arrested over the issue.

The movement had many unsung heroes as well, Wilson said. One was Emily Pierson, an English teacher who became active in the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association and used organizing skills, effective tactics, and automobiles to help bring the message to small towns, working with speakers of various languages and with both working men and women.

Another lesser known player was Edna Purtell, who at age 19 went to a Washington, D.C., National Women’s Party demonstration in a trip funded by Hepburn. Purtell got herself arrested and even injured, in standing her ground.

Wilson also told of Mary Townsend Seymour, an African American woman from Hartford was one of the founders of that Hartford chapter of the NAACP and worked on issues such as segregation, lynching, immigration, and political organizing for tobacco workers.

“For Seymour, racial equality and women’s suffrage were not two separate issues,” Wilson said, adding that it was generally that way for African American women.

Seymour also stood up to National Women’s Party leaders, including the well-known Alice Paul, when they failed to fight for black women’s rights in the suffrage question. Many of those national leaders felt inclusion would further deter southern politicians from backing the effort.

“Racists arguments in the suffrage battle surfaced often,” Wilson said.

Seymour was one of the many African American women who have not been adequately recognized in the struggle, said Wilson, who noted that Seymour, Purtell, and Stewart are absent from a plaque in the state capital honoring Suffragettes.

“Do you think we need a new plaque as we discover more about this history of this movement, 100 years later?” Wilson asked the audience.

Along with those who fought for women’s suffrage in the state, there was opposition, even among women.

Circa 1910, the Connecticut Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage formed, asserting the role of the woman should be non-political.

Powerful politicians, sometimes arguing that the issue was a state’s rights one, also fought the movement. Connecticut Senators Frank B. Brandegee and George P. McLean, for example, both voted against the 19th amendment.

And Connecticut missed the chance to be the crucial 36th state needed for ratification.

“In Connecticut a special session of the General Assembly needed to be called but Gov. [Marcus] Holcomb refused to see this as an emergency,” Wilson said.

But while Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, Connecticut would do so later in 1920.

But despite the resistance in those years, the issue in Connecticut, and elsewhere, was more complicated yet. Women had gained some voting rights in the early 20th century.

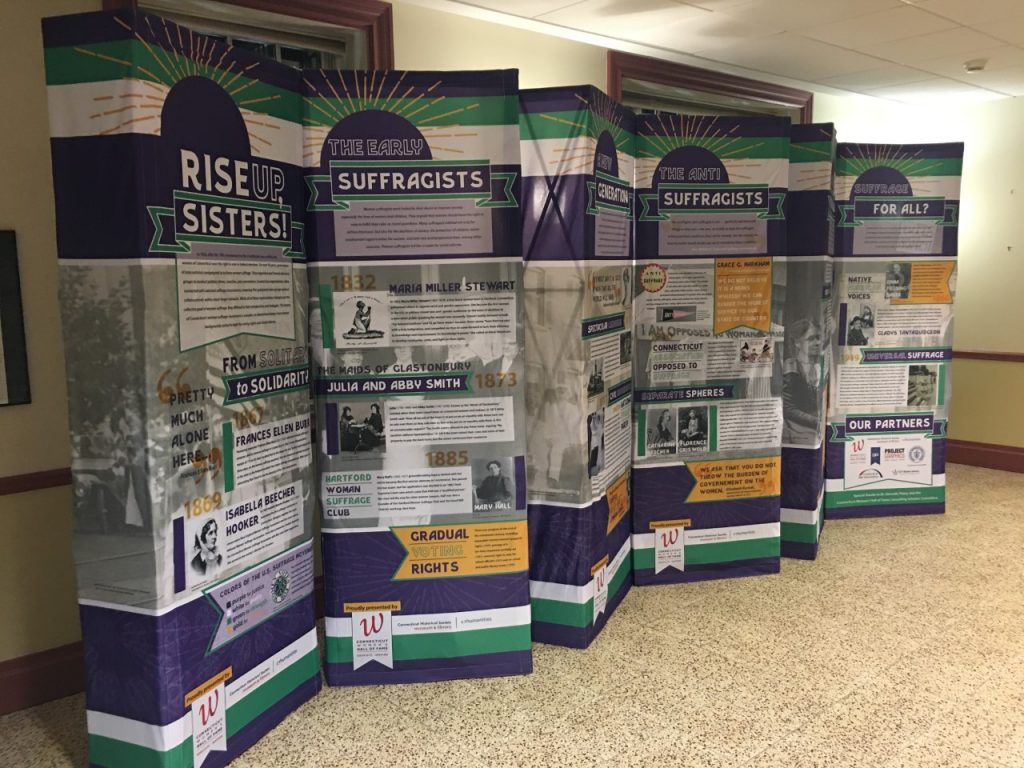

The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame loaned banners for the evening. Photo credit: John Fitts

“The 1914 map of suffrage in the United States was complicated,” Wilson said. “Men in Western states voted for suffrage, men in the South blocked it, and in the Midwest and the Northeast, women had what was called partial suffrage,” she said noting that women could often vote in municipal elections, and in library boards and for school issues.

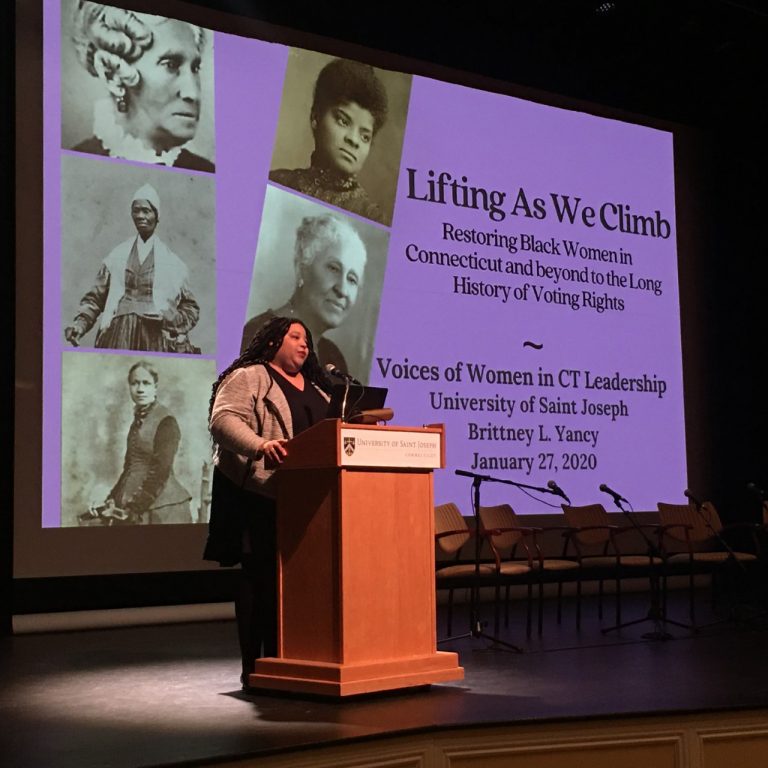

But honoring the women who fought for the more universal right to vote was certainly a key focus of the USJ event. Picking up on the theme of those who have not been properly recognized was Brittney Yancy, Assistant Professor of the Humanities at Goodwin College, who presented “Lifting as We Climb: Restoring Black Women in Connecticut and Beyond to the Long History of Voting Rights.”

“What I hope to do is to offer a narrative that doesn’t often get told about the way African women and indigenous women, and women of color shaped the conversation of suffrage and overall advanced the idea of the right to vote and really influenced the struggle for that,” she said.

Yancy actually started with a woman who is well known and was even the subject of a recent film, Harriet Tubman, known for her track in life from slave to famous abolitionist.

But the film and many other accounts say little about her work as a suffragette.

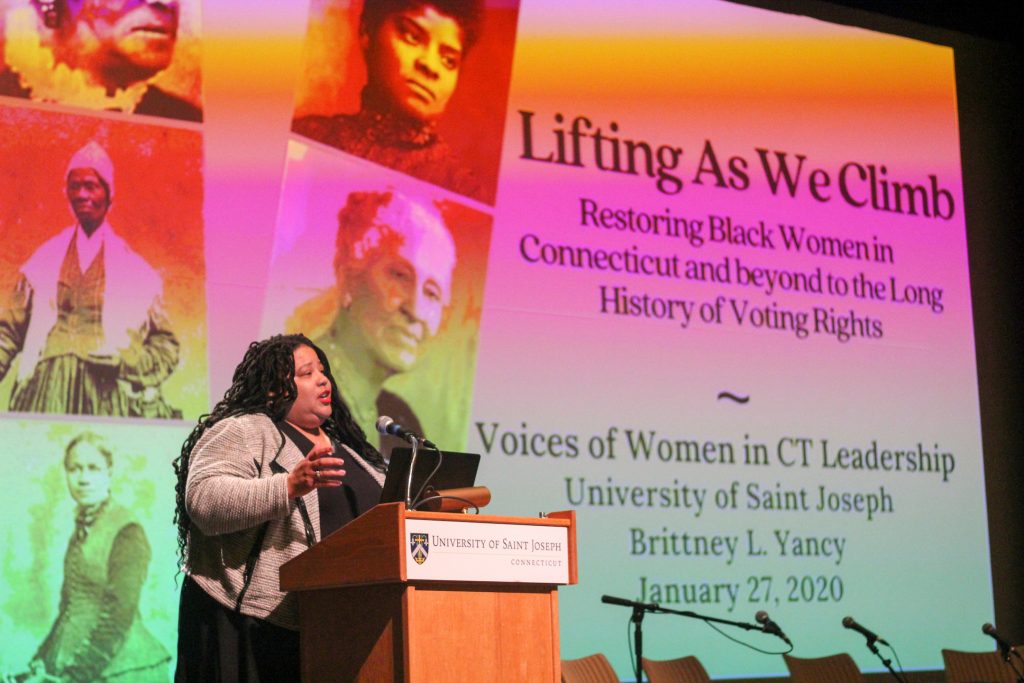

Brittney Yancy, Assistant Professor of the Humanities, Goodwin College who presented “Lifting as We Climb: Restoring Black Women in Connecticut and Beyond to the Long History of Voting Rights.” Photo credit: John Fitts

“The mere flash of a mention that she was involved in the suffrage movement left me puzzled,” Yancy said about the film. “It would have been awesome to understand the friendship and tension between Harriet Tubman and her friend Susan B. Anthony. Wouldn’t that have been interesting to understand?”

She noted other highlights, such as an 1896 national association for colored women club that met in Washington, D.C. and picked Tubman as its speaker.

“Sure enough they’re looking for inspiration to inspire black women to carry on this charge of not just suffrage but overall equality and democracy. Surely Harriet Tubman is the person they select, and they refer to her as ‘Mother Tubman’ when she arrives,” she said. “Can you imagine coming to a convening and Harriet Tubman is the keynote speaker? What an amazing feeling that must have been.”

“I use Harriet Tubman as an example of how when we talk about black women’s contribution in American History, there is a minimalist approach. We get very comfortable with half-truths and convenient omissions …

“What I hope to do as a historian is to paint a longer history and restore black women to American history and think about this cohort at the turn of the 20th century is not random black women coming together.”

Yancy noted another important moment of the women’s suffrage movement, the Seneca Falls Convention in July of 1848. While the convention included famed abolitionist, activist, orator, and writer Frederick Douglass, it lacks another dimension.

“There is no record of women of color that were invited to Seneca Falls that is supposed to be a national convention and convening of women talking about suffrage,” she said.

That, along with a famous statue from the convention, might give the impression that African American women were not involved, and nothing could be further from the truth, Yancy said.

Like Wilson, Yancy acknowledged the work of Stewart, who started speaking publicly in 1832.

“She is actually our nation’s first American born woman, regardless of race, to speak out on political issues, in front of a mixed crowd, which was not welcomed at the time,” she said. “It is important to understand that Maria Stewart is critical to this state’s history and I join my sister historian in the fact that we do need something that honors her in a much more powerful way in this state.”

She also noted other Connecticut women such as Mary Townsend Seymour, a charter member of the Harford Branch of the NAACP in 1917.

“She really becomes the model of how to build cross racial alliances in the suffrage movement,” she said. “Her relationship with Josephine Bennett is critical to her own work.”

Seymour in fact ran for state representative for the Farmer-Labor Party ticket in 1920, ran two years later for secretary of state and ran for the Board of Education in Hartford, Yancy said.

“Mary Seymour is the first African woman to run for state office here in Connecticut. That is critical. That needs to be part of the conversation. …. How can we not know her? How can we not celebrate her in this moment? … We are missing critical elements in this history. There are plenty of African Americans, plenty of indigenous groups, plenty of women of color, Chinese women. …. We don’t even acknowledge that or include that in the narrative.”

And Yancy said there are so many more that have not yet been written into history at all.

In the struggle for equality, many groups met in clubs or churches, she said. Some, like the Northeastern Federation of National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, have been documented but others have not.

That evening she announced that a CT Humanities grant awarded to the Connecticut Historical Society will give her and others the chance to work with institutions such as museums, churches, and historical societies to uncover some of the others who were meetings in clubs and churches. The $4,500 grant will include six presentations in the state about the research, according to the CT Humanities website.

“I think once we learn more about these narratives and who these women are in these clubs that it’s going to unlock a history that has yet to be told,” Yancy said.

Brittney Yancy, Assistant Professor of the Humanities, Goodwin College who presented “Lifting as We Climb: Restoring Black Women in Connecticut and Beyond to the Long History of Voting Rights.” Photo credit: John Fitts

Yancy and other speakers of the evening also noted another forum that had been used for activism – sororities like Alpha Kappa Alpha, of which she is a member, which started at Howard University in 1908.

Another was Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, which began in 1913, and importantly was part of the Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C. on March 3 Suffrage of that year – although they were relegated to the back of the parade.

At the USJ event, several alumnae of the Hartford chapter of Delta Sigma Theta were present and received enthusiastic applause.

“When we talk about the role of the sororities, we kind of take it for granted and really haven’t unpacked the contribution they made to the struggle for voting rights then and now,” Yancy said.

The final speaker of the evening, before a panel discussion, was Merrill. She not only noted the complicated history and the fact that it took until 1965 for true equality in voting rights but also mentioned several other factors of the suffrage movement.

Women suffragisits, she said, were first lobbyists and brought aspects such as color and pageantry and parades into the movement.

“They laid a great foundation for the civil rights movement and other non-violent acts that came later,” she said.

She also recounted the story of how Tennessee became the deciding state, due to one young man who was an anti but was persuaded by his mother, also originally an anti, who had changed her perspective. He went with his mother’s wishes despite intense pressure from fellow politicians.

Merrill suggested that the crowd consider reading “The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote” by Elaine Weiss.

“As the speaker of the house sat there with his arm on his shoulder this guy voted yes and turned the tide of American history. That’s why I love American history. It’s so full of moments like that.”

Merrill also touched on some other reasons many men finally came around.

“They all started realizing that this was a huge new block of voters all across the country and in every state that played out,” she said.

Merrill also touched on several other factors, such as that women never quite became the “voting” block many expected, and that progress has sometimes been slow, or even rolled back.

She said the crucial voting act of 1965 has been weakened somewhat after a Supreme Court decision that allowed states to make changes to voting rolls without federal approval. That has led, she said, to moves such as purging of rolls right before the election.

“Today there is a fairly organized effort to roll back some of those things so here we go again with the push and pull of history,” she said.

One example Merrill cited is voter photo identification laws. While she said the idea sounds very rational, she argued that it’s the type of identification that is selected that sometimes targets people of color, young people, older folks, and the poor. In Texas for example, a gun license is acceptable but not a college identification card.

“That’s an example of the kind of subtly your seeing in some of the things going on,” she said.

So, the fight is not over, Merrill said.

“The struggle continues … this is something that this country and others I’m sure will always fight because voting is power and that’s what these women had figured out – and Dr. Martin Luther King as well.”

But Merrill also said she is incredibly grateful for the women who fought so hard for this issue.

“People died. They were tortured, they were sent to prison I’m just so humbled by that. I don’t know if I would have had the fortitude for that. … I hope I would that’s something I really think about? Where are we today. That block of voters did not materialize but we definitely lean on each other I would say. … I rely so much on my female colleagues to talk to run ideas past. Women are still very powerful advocates and especially children and families and healthcare and all the things all of us care about.”

She also mentioned the recent wave in female candidates, something that came after a long period of stagnation in the numbers of women serving.

“The struggles continues, and the place of women is still not secure. These things can be rolled back at any moment, we actually lost ground in terms of women running for office, until 2016 and 2017 and all of sudden I feel like we have found our voice and there’s a lot of reasons for that. We have the whole #MeToo movement, and people are speaking out, and it’s really making a difference we are passing legislation we never could have passed without those voices right now – not only here but across the country. We continue to need those powerful voices and we do stand on the shoulders of these people, and we’re implementing all the techniques they used and then some.”

And there’s still much to contemplate, Merrill said.

“We have a lot to learn but there’s a lot of questions still in my mind about what this all meant and where we’re going from here.”

Voices of Women in CT Leadership: A Celebration of the Centennial Anniversary of Women’s Suffrage was a program of the USJ Women’s Leadership Center.

Upcoming programs include Global Changemakers: International Women’s Day Celebration from 5 to 7 p.m. on Tuesday, March 3, in the Bruyette Athenaeum, Hoffman Auditorium, and Where are the Women? Rediscovering the Origins of Connecticut Women Artists from 5 to 7:30 p.m,. June 25, in the Bruyette Athenaeum Art Museum.

See more at usj.edu/wlc.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!