An Interdependent Colonial World

Audio By Carbonatix

The Whitman house at 208 North Main St. Courtesy of Tracey Wilson

This is the fourth in a series of history articles provided by West Hartford Town Historian Tracey Wilson, as we all make our way through the pandemic of 2020. Wilson hopes the articles can provide a diversion, and invites comments by those who remember or know something more about the topic. Many will be excerpts from her 2018 book “Life in West Hartford.”

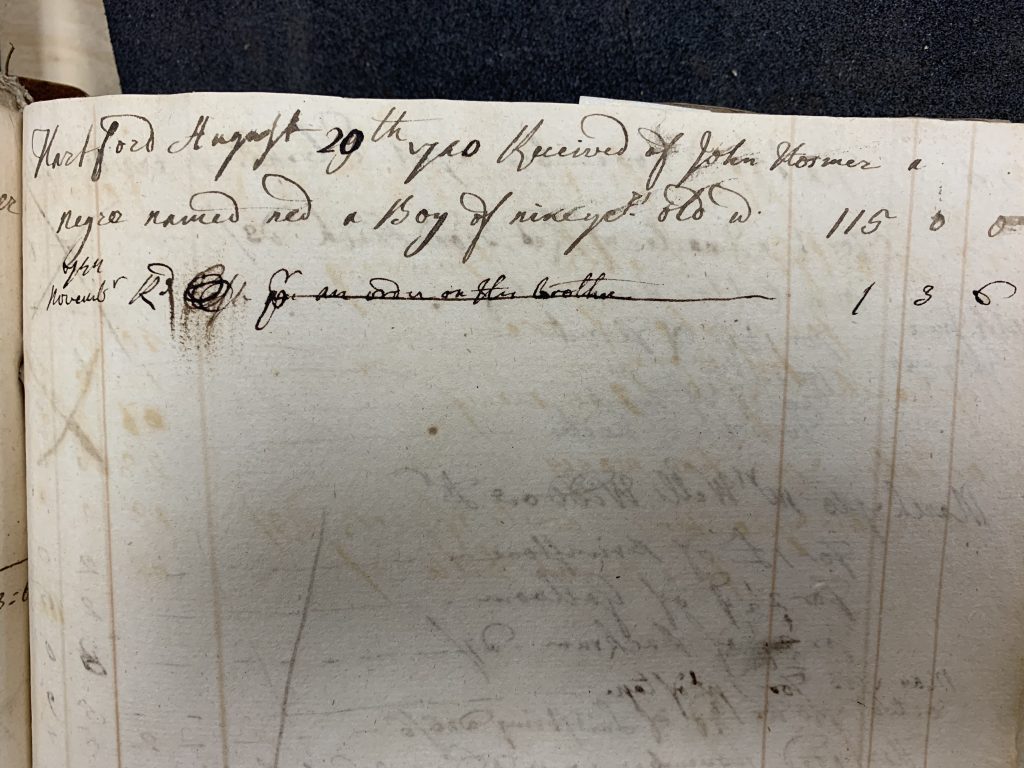

Entry showing the purchase of 9-year-old Ned. Courtesy of Tracey Wilson

By Tracey Wilson, Town Historian

Hunkered down in our homes during this pandemic, we are more acutely aware of our interdependence. Many of us are living in our bubbles at home, yet we still need that delivery of food, medicine, cleaning products, or seeds. We yearn for human connection which our technology allows at a level.

Today interdependence is a given.

Were we interdependent 270 years ago in the West Division of Hartford? Were families self-sufficient, a storyline that many of us came to believe from our education? Farm families took care of all of their needs by planting, husbandry, spinning, and weaving, our teachers told us.

Front cover of John Whitman’s account book. Courtesy of Tracey Wilson

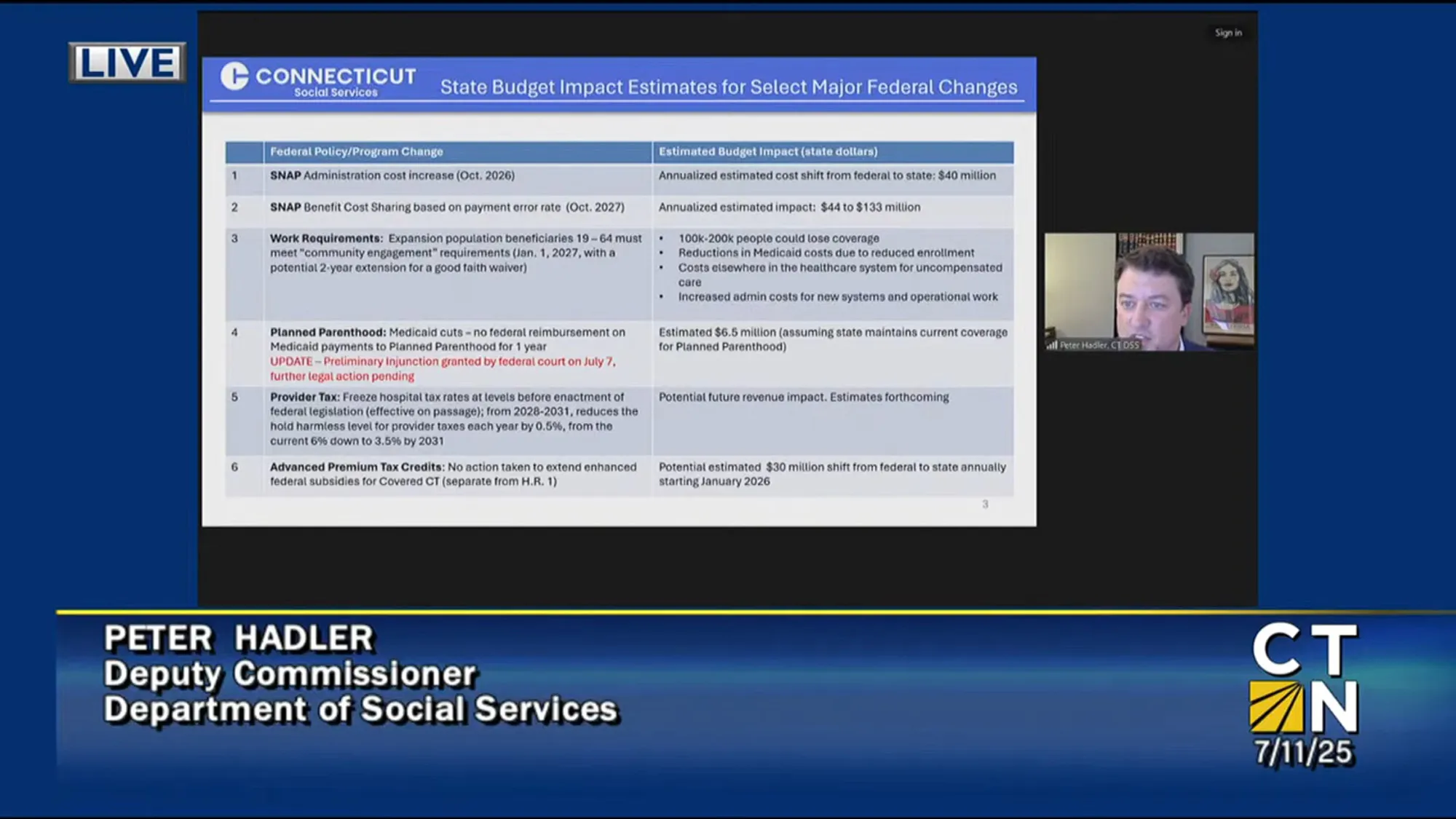

The account book of John Whitman (1712-1800), a local merchant, tells quite a different story, one of an interdependence and human connection that defined daily life and the local West Division community. This leather bound account book, held by the Connecticut Historical Society, is a puzzle and a treasure that helps us reconstitute this 18th century world through his transactions.

It tells a multicultural story, too. The account book can tell us stories of enslaved men born in Africa, the Caribbean, and America, the Wangunk and the Tunxis, women and men with whom Whitman traded. In the mid-18th century, colonial merchants kept track of every transaction and at certain intervals, reckoned with the person they traded with. Pages in this book help us to understand the connections among those who lived and worked here, and helps us to learn how interdependent this colonial economy was.

John Whitman grew up in Farmington where his father, Rev. Samuel Whitman (1676-1751) served as the minister of the Church of Christ. Rev. Whitman began a school for Indian youths and the church set aside a gallery for their use, according to Chris Bickford in his local history “Farmington in Connecticut” (1988). While two of his sons became ministers, John became a merchant and farmer in the West Division of Hartford.

John Whitman married Abigail Pantry in 1738, and between 1739 and 1753, they had six children. He built the house, still standing at 208 North Main St., in 1764, when he was 52 years old. His son John, Jr. (1741-1813) designed the house. Their property, house and barns, of about 60 acres ran from Main Street east to Trout Brook. As the brook went down the hill, the falls were named Whitman Falls. This property most likely came to Whitman through his wife Abigail Pantry whose father John was a landholder in the West Division and died in the early 18th century.

Whitman traded with his relatives. On Feb. 15, 1774, Thomas Hart Hooker bought cheese and butter from John Whitman. Hooker married John Whitman’s daughter Sarah Whitman and moved into the house, still standing at 1237 New Britain Ave., soon after they married in 1769.

It was Thomas Hart Hooker and Sarah Whitman Hooker who enslaved Bristow who bought his freedom from Hooker in May of 1775. Hooker went off to fight with Connecticut’s Second Regiment in Boston and died later that year. Who made the five trades listed in the account book after Thomas left for war? Did his wife travel down Main Street with her two young children? Did the enslaved man Amboy make the trade?

Whitman traded with people from Farmington. In October 1744, he traded with John Smith “for 1 Indian blanket to Thomas Indian.” Was John Smith a man John Whitman knew in his youth? Did Thomas attend Rev. Whitman’s Indian school?

Whitman traded with women. In March, 1761, John Whitman started a page for Widow Catharine Thomson. She bought 1 ½ yards of black Everlasting, a high grade woolen material. She bought two hanks of silk and a button jacket. Thomson would fashion the woolen and silk into clothing of some sort. By May she had balanced her account. In June 1762, Whitman traded with Widow Dinah Merry. She bought two quarts of brandy, and paid for Whitman pasturing her mare. Had either woman traded with Whitman before their husbands died?

Whitman traded with neighbors. In August 1740, he received an enslaved boy who John Hosmer traded to him. The entry reads: Hartford, August 19th 1740 Received of John Hosmer negro named Ned a Boy of nine years old worth 115 pounds.

Hosmer and Whitman valued Ned at 115 pounds, the equivalent of $28,000 today. How did this transaction happen? The Hosmers lived across the street from the Whitmans. Did John Hosmer walk across the street with this 9-year-old boy and, just like that, Ned became the property of John Whitman? In December 1740, Whitman got a coat for Ned, the entry reading: “December 1740 Received for Credit out a coat for Ned 10 shillings.” In November 1744, when Ned was 14, the local shoemaker John Seymour, brought shoes for Ned. The entry reads: “Received a pair of shoes for Ned 9 shillings.” Ned was a financial investment to Whitman and his neighbors were complicit in his enslavement.

Whitman traded with enslaved people. In February 1760, John Whitman traded with “Page negro.” Page bought Holland cloth, a hank of thread, and a pair of stockings. With “Dick, Negro,” he traded for a cup, 1 ½ dozen buttons, a hank of silk, and a ½ yard of buckram (a stiff cotton/linen cloth with a loose weave). To Caesar, he traded 1 ¼ yards of Brown Holland cloth, a string of beads, a pair of buckles, and a cotton hank all in 1749. Caesar was enslaved by John Whiting. Where did Page, Dick, and Caesar get their money? Did they use their skill of tailoring to make money on the side?

John Whitman traded with the Tunxis. In March 1765, Whitman traded with “Occusk an Indian belonging to Farmington.” Occusk bought Indian corn, cyder, pork, milk, brandy, a load of wood, cheese, sugar, lamb, penny nails, knife, and sugar. How did Occusk get to Whitman’s and how did he get his goods back to Farmington?

Whitman’s account book gives us a picture of his house being the hub of interdependence in this colonial town of about 800 people. He and other merchants set prices and gave as fair a trade as they were willing to those who came to them. Did family members get a break? Were townspeople upset that he traded with the Tunxis and enslaved Africans? Was it difficult for widows to learn how to do these transactions? Was Whitman “just” in his trade? He passed the account book down to his son when he died in 1800, and the house remained in his family until the Duffys bought it in 1897.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford, and click here to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.