Ben Cooper is Nearly 100, and Has Served His Country for Nearly 80 Years

Audio By Carbonatix

World War II veteran Ben Cooper, 99, outside his West Hartford home. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

World War II veteran Ben Cooper of West Hartford shares his story.

By Ronni Newton

Ben Cooper still fits into his Eisenhower jacket with the thunderbird logo, and he still speaks about the importance of freedom, and loyalty, and sacrifice.

And despite having witnessed horror and unspeakable tragedy, he remains positive and optimistic, handing out his signature card to everyone he meets, a card which states: “Save humanity Stop hatred and bullying by practicing my life saving motto – ‘No act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted.’ You can do it! Never give up! Always remember we all belong to the same race … the human race.”

Cooper will turn 100 this December 24th.

“I wanted to serve my country,” Cooper, a World War II veteran, said during a recent interview.

Just shy of his 20th birthday when Pearl Harbor took place, Cooper wasn’t sure which branch of the service he wanted to join, so he waited until he was drafted, which happened in 1942.

A lifelong West Hartford resident – other than his time in the military service – Cooper, who grew up at the corner of Prospect and New Park avenues, had worked at Colt testing machine guns before he was drafted. He even had a letter saying he was a weapons expert, but when he reported for service with the U.S. Army at Fort Devens in Massachusetts, they looked at the letter – and then assigned him to be a medic and sent him to Fort Barkeley in Texas.

“I knew how to put on a band-aid,” he said.

Although he readily accepted the challenges the Army threw his way, Cooper was strong-willed about other facets of his life.

First comes love, then comes marriage

On his first furlough from Texas Cooper returned to visit his family in West Hartford. A friend asked him if he’d like to meet “a nice tomato” – a term at the time for a pretty girl, and describing a cousin who was visiting from Maine.

“There was this beautiful girl – ironing,” Cooper said, laughing as he recalled a scene that happened nearly 80 years ago when he met Dorothy, who was getting her dress ready for a date that night with someone else.

Immediately smitten, and undeterred, they started writing letters. GIs could use the U.S. Mail for free at the time, he said.

On his next furlough, Cooper went to visit Dorothy in Maine.

They went to the movies with another couple – and by the time the movie ended they were engaged.

Cooper promised Dorothy’s father that they would wait until after the war to get married, but in 1944 he was notified that he would be sent overseas. He had seven days before being shipped out.

Phone calls were complicated back then, and it took five or six hours to connect a call from Texas to Maine. When the call to “Coppy” – his nickname for Dorothy, who had beautiful red hair – went through, “I asked her, ‘Do you want to get married?’ Cooper said. She said, ‘Sure.’”

His parents picked him up at the train station in Hartford, and they traveled to Old Orchard Beach, Maine, where on July 14, 1944, Ben and Dorothy were married in small synagogue. The day was steaming hot, and the windows were wide open, allowing tourists to watch the ceremony. “It was like a show going on,” he said.

Soldiers weren’t supposed to get married to women they hadn’t known for a specified period of time, Cooper said, and his brief relationship with Dorothy wouldn’t have qualified them to get married. Her mother’s cousin’s ex-boyfriend was a judge, however, and agreed to vouch for their relationship.

The newlyweds had a brief honeymoon in Ogunquit before he left for Europe, and his new wife stayed with her parents in Maine.

Cooper and Dorothy were married for 65 years, until her death on Aug. 25, 2009. They had four children. His daughter, Sharon Lingenheld, and his son, Rick, along with Rick’s wife, Theresa, joined Cooper for this interview. Lingenheld, who was widowed in 2019, now lives with her father in the same West Hartford home where she grew up. Cooper is still very independent, but he does walk with a cane and has stayed close to home for the past 20 months due to COVID-19. Sharon, Rick, and Theresa help with many day-to-day tasks.

Cooper’s daughter Nancy lives in Maine, while another daughter and son-in-law, Cindy and Mike Donoghue, and their son, Tyler, live in Elmwood.

The war

“We boarded a Liberty ship,” said Cooper, who was serving with the U.S. Army’s 45th Infantry Division. They headed across the Atlantic Ocean.

Cooper has a collection of artifacts from World War II, including a helmet. But it’s not the one he was first issued.

While on watch, and headed through the Mediterranean, Cooper bent over the edge of the ship to look at the phosphorescence in the water. “My helmet slipped off,” he said. He briefly considered jumping in to retrieve it, but decided to instead risk the reprimand he knew he would receive from his commander at roll call the next day.

Cooper went to Naples, and then Marseilles, where they had to take a duck boat to reach the shore because the port had been bombed out.

The freight train the soldiers took to get closer to the front lines was called a “40 or 8,” Cooper recalled, meaning each car was intended to transport 40 men, or eight horses.

Arriving at night in a rural area, his unit was told to sleep in the loft of a barn.

When they awoke the next morning, “We got the shock of our life,” Cooper said.

They were suddenly face-to-face with the tragedy of war. They had been sent to sleep in the loft because the floor of the barn was where overnight the bodies of the soldiers who had been killed the previous day were brought to be tagged, their deaths officially registered by the Army.

“My dad was a medic. He didn’t carry a gun,” Sharon said. But that didn’t mean he faced less danger, or tragedy.

Artifacts from World War II include a helmet, leather medic’s bag that had belonged to a German soldier, a “Juif” Start of David given to Cooper by a man in France, and his letter to Dorothy sent at the end of the war. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Cooper still has stories he shares, some that he can laugh about decades later, like the time he was transporting a soldier with a broken leg back to an aid station when he heard a voice. It was coming from another solder, camouflaged atop a Sherman tank, who informed Cooper that he was heading in the wrong direction – toward the front lines, rather than the aid station.

During a brief furlough he visited Lunéville, France, where he found a synagogue. Outside was a father with three children. “I took French at Hall High,” said Cooper, and he struck up a conversation.

They took a photo together, and the man gave Cooper the Jewish star that he had been forced to wear on his clothing when the Nazis occupied the area. “Juif,” it said, French for “Jew.” Cooper still has it.

In a twist of fate, decades later, after giving a presentation to a class in Simsbury, a teacher was determined to find out who was in the photo. Cooper was reconnected with Arlette Solomon, now in her 80s, one of the children he met that day in France.

He also recalled a visit to a high school in France, where he was on the second floor listening to someone play a piano, when suddenly there was a face in the window. “It was the tallest guy in the world,” Cooper said, a man who he said was more than 8 feet tall and could look in a second-story window.

In France they liberated towns, but then his unit headed to Germany, where they “captured towns,” Cooper said. As a medic, he was focused on taking care of the wounded soldiers, and he had become a good cook. Having learned Yiddish growing up he also could get by with some German.

“I’d knock on the doors and said, ‘Haben sie frisch Eier heute?’” (Do you have any fresh eggs today?)

In one town, the shelves in a store were empty, but Cooper said he found a crate around back, labeled “300 Eire.” Every solder got a dozen eggs that day.

Cooper carried scissors, bandages, and sulfa powder – “miracle powder” to treat wounds – in his medic’s kit. His own bag was damaged by gunshots, but he has a replica, and he also still has a leather medic’s bag that he kept for the rest of the war after confiscating it from a German soldier who surrendered to the Americans.

In July 2019, Ben Cooper of West Hartford receives the Knight of the Legion of Honor Medal from French Consul General Anne-Claire Legendre. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

The worst war story

In late April 1945, Cooper left on a transport from Munich, heading to Dachau. The 45th had fought its way into Dachau he said, and had begun to liberate the concentration camp.

As the transport neared, “There was a terrific odor in the air, of burning flesh,” Cooper recalled.

Eisenhower sent as many soldiers as possible to Dachau when it was being liberated, to witness the atrocities that were found there.

“What I saw was unbearable. It was unbelievable,” Cooper said.

There were plywood barracks, built to house 400 people, but 1,400 had been forced to live in each one, people who were so emaciated you couldn’t tell if they were men or women. If they weighed 60 or 70 pounds it was a lot, said Cooper.

They were starving, but Cooper said the soldiers were told not to give them food or drink, because they wouldn’t be able to swallow it much less keep it down.

Home, at last

After Dachau, Cooper headed to Munich.

“Then Dad wrote the one and only letter to my mother,” Rick said.

Cooper said he had watched too many soldiers write to their loved ones, letters that ended up being the last ones they ever wrote. He decided if he didn’t write, he would stay safe.

In Munich he penned a four-page poem to Dorothy (which can be read in the sidebar).

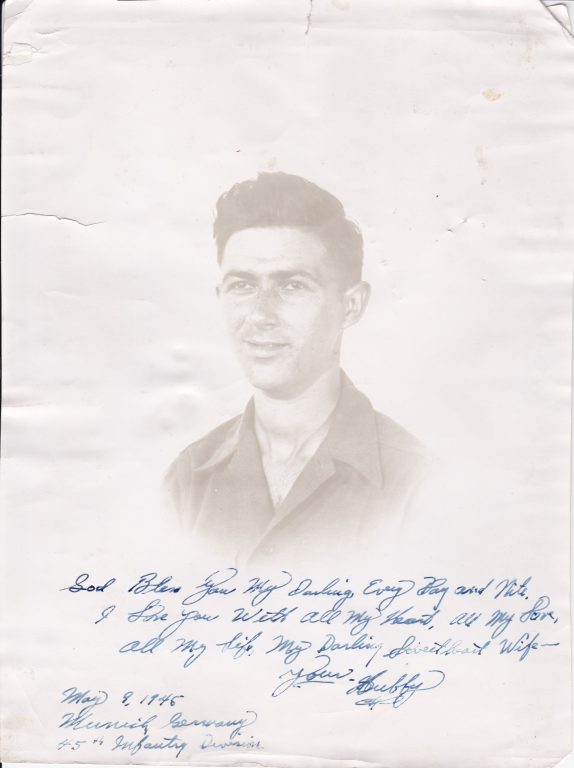

Along with the letter, which was dated May 8, 1945, Cooper sent Dorothy an inscribed photograph of himself.

Cooper read the letter aloud to his family one Passover, unable to get through it without tears.

“My dad never talked about the war when we were growing up,” Sharon said. “It’s unbearable for me to think of him being there. He’s the most gentle man.”

In 1990 a local social studies teacher asked Cooper if he would participate in a videotaped interview about World War II. That began his new mission, and since then he’s spoken to countless groups of students, civic leaders, and other veterans about the Holocaust and his service in the war. He would read the letter at the end of his talks, eventually getting through it without tears.

“It was healing for him,” Sharon said.

Rick said it was healing for his children as well.

Cooper went to England, and sailed back to New York aboard the Aquitania. As they entered the harbor late in the summer of 1945, the ship listed heavily to one side because all the soldiers were standing there to catch sight of the skyline and the Statue of Liberty.

Fire boats shot streams of water from their cannons into the air to welcome the soldiers home.

Cooper had a brief reunion with Dorothy in New York, but then she went back to her parents’ home in Maine while the Army kept Cooper in Fort Dix for a while longer, checking the blood pressure of returning soldiers, before he boarded a train to Hartford and then the Charter Oak Park trolley down New Park Avenue to his parents’ home.

He and Dorothy lived on New Park Avenue, and then bought a house on Griswold Drive.

The house where Cooper still lives, on East Maxwell Drive – in a neighborhood called Hunter Park – was new when he and Dorothy bought it in 1957.

Ben Cooper outside his West Hartford home with his daughter Sharon Lingenheld (left), son, Rick Cooper, and Rick’s wife, Theresa. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

More love to share

A few years after Dorothy died Cooper’s friends from the Jewish War Veterans wanted to set ho up with a widower they knew. Henny Simon, a few years his junior, had been sharing her own Holocaust experiences to school and civic groups.

The first time he was supposed to meet Henny, he had fallen asleep and didn’t make it to the event, but he made up for it by going to visit her at her Colchester home.

She told Cooper her story.

“She’s a tough cookie,” he told his children when he returned to West Hartford. While Henny was sitting and talking with Cooper, he had spotted a knife strapped to the side of her calf.

Turns out it was an epi-pen.

While he and Henny never married, they were very much a couple until her tragic death in a car crash in 2017. “He had a second chance at true love,” Sharon said.

Rick said they did their talks together, the “Benny and Henny show,” he said, which is the subject of a documentary now in production.

Cooper’s love, and loyalty, and his positive attitude, have stayed with him. And he has always had a way with words. “You never lose the one you love if you love the one you lose,” he said.

Cooper has an iPhone, and while Sharon lives with him, he checks in daily with his other family members, and FaceTimes his daughter Nancy in Maine.

He still hands out his card to everyone he meets, including reporters.

Cooper’s activities were curtailed greatly by COVID-19, but until then he regularly attended Roll Call, a community discussion for veterans from all branches of the armed service that he had established years ago.

Cooper was inducted into the Connecticut Veterans Hall of Fame in 2017, and in June 2019 received a Connecticut Wartime Service Medal and a Certificate of Special Recognition. Also in 2019, he received the “Légion d’Honneur” from the French Consul General in a ceremony at the Connecticut State Capitol, an honor awarded to living veterans who risked their lives during World War II while fighting on French territory.

“I speak from my heart. It’s right here,” Cooper said, putting his hand on his heart.

“We all saved humanity at that time.”

The following poem was written by Combat Medic Ben Cooper at the end of WWII to his wife, Dorothy.

A photo that Ben Cooper sent to his wife, Dorothy, with a letter, when World War II had just ended. Courtesy of Cooper family

WHAT CAN I SAY MY DARLING

WHEN WORDS I CAN NOT FIND,

TO EXPRESS MY LOVE FOR YOU

MY BELOVED DARLING WIFE

AND THO WE’RE MILES APART,

YOU ARE AND HAVE ALWAYS BEEN,

RIGHT HERE INSIDE MY LONELY ACHING HEART,

AS I SAILED ACROSS THE OCEAN BLUE,

AND THRU THE STRAITS ON A LIBERTY TO ITALY,

AND THERE RECEIVED WITH SO MUCH GLEE, YOUR INSPRIRATIONAL LETTERS,

WHICH MEANT SO MUCH TO ME….

AND THEN TO FRANCE WHERE I WAS GIVEN A JOB, FAR DIFFERENT FROM THE ONE I THOUGHT I WOULD HAVE FOUND,

ANOTHER FELLOW WAS DOING HIS PART

‘TILL THE FICKLE FINGER OF FATE HAD FOUND HIS HEART.

AND NOW I WAS TO CARRY ON.

I PRAYED MY DARLING THAT I MAY LIVE,

TO SEE MOTHER AND DAD AND YOU MY DARLING SWEET.

I PRAYED THAT YOU AND I MAY BE ONE AND HAVE OUR OWN IN OUR OWN HOME,

I PRAYED EACH DAY IN MY OWN WAY,

SOMETIMES IN FOXHOLES IN THE RAIN,

OR COVERED WITH SNOW—OOH SOOO COLD.

OR IN A HOUSE WHERE I WOULD FEEL A

LITTLE SAFER FROM THE SNOW AND THE

RAIN AN THE COLD,

BUT MOST OF ALL, THE HOT SCHRAPNEL OF

BURSTING SHELLS THAT KNEW NO MAN

FATHER, UNCLE, BROTHER, COUSIN,

AN ONLY SON, ONE OF A DOZEN,

CATHOLIC, JEW, PROTESTANT, BLACK, WHITE, GOOD, BAD, CARRIED A GUN OR A RED CROSS ARMBAND.

G’D WILL THIS WAR EVER END?

ATTACK AND ATTACK DID THE INFANTRY,

RIGHT ON INTO GERMANY-

BUT NEVER KNOWING FROM WHERE OR WHEN

THE ENEMY MAY TRY TO STRIKE

BACK AGAIN AND DO THE THINGS THAT WAR

IS HATED FOR.

THERE WERE BIG TOWNS AND SMALL TOWNS,

RIVERS AND STREAMS, ROAD BLOCKS AND TREES, AND SO MANY THINGS.

THE PEOPLE SEEMED FRIENDLY AT LEAST SO IT SEEMED.

WHAT WAS HAPPENING TO HITLER’S DREAM?

WE TRAVELED IN CONVOYS FOR MILES AT A STRETCH,

DUSTY AND DIRTY OR TIRED AND WET,

SEARCHING FOR JERRIES AND SNIPERS-

THOSE RATS!!!!!!!!!!!!!

HOUSES WERE BURNING, AND CATTLE LIE DEAD

—OOPS BE CAREFUL—THEY SAY

THERE’S MINES UP AHEAD.

HOW COULD YOU HATE SUCH PEOPLE AS

THESE—WHO GAVE YOU THEIR EGGS AND

BEER FROM THE KEGS—-

EVERY MINUTE OF THE DAY –YOU COULD

HEAR THEM SAY—NIX NAZI.

OH SUCH NICE PEOPLE I DARE SAY,

BUT THEN CAME THE HORROR AND

CRUELTY BEYOND ONE’S IMAGINATION

COULD PONDER UPON—THERE WAS

DACHAU, BUCHENWALD AND MORE CAMPS ABOUT

WHERE CIVILIZATION WAS SIMPLY

WIPED OUT.

THIS WAS OUR ANSWER TO WHY WE FOUGHT ON

—AND HOW OUR HATRED FOR THE GERMANS WAS FOUND.

AND AS TODAY I REMINISCE

OF ALL THE BOYS WE SURE DO MISS,

I CANNOT HELP BUT SAY A PRAYER FOR THOSE WHO FELL—

MAY THEY REST IN PEACE:

COHEA, KELLER, KANE AND SAYLES—AND A

PRAYER FOR THOSE WHO LIVE.

OH DARLING, I DON’T FEEL ANY SMARTER

FOR AL THE THINGS I’VE SEEN AND DONE.

I JUST FEEL, OH, SO LONESOME FOR YOU MY

DEAREST ONE AND ONLY ONE.

AND I HOPE AND PRAY THAT SOME DAY,

I’LL BE SAILING BACK ACROSS THE OCEAN BLUE

TO YOU.

TO LIVE AND LOVE AS TIME GOES BY

IN OUR HOME FOR 2 OR WAS IT 4? OR MORE?

AND VANISH THE LONESOMENESS

THAT’S IN MY HEART—FOR YOU

MY SWEETHEART, MY DARLING WIFE.

TIL THEN, G’D BLESS YOU EVERY DAY AND

NIGHT—-SWEET DREAMS, SWEETHEART—

I LOVE YOU WITH ALL MY HEART.

YOUR HUBBY,

BEN

MAY 8, 1945, MUNICH, GERMANY

179TH– INFANTRY, 45TH INFANTRY DIVISION

A version of this article originally appeared in the November issue of West Hartford LIFE

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

An outstanding story about an outstanding person, Ben Cooper.

Happy Birthday to Ben Cooper from a West Hartford Sedgwick & Conard alum.

Sincerely,

Jim Johnson

http://www.JamesAJohnsonEsq.com