Bristow and Ambo, Local Veterans

Audio By Carbonatix

A headstone commemorating Bristow is next to the Witness Stones that have been installated at Old Center Cemetery in West Hartford. June 19, 2021. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

Until recently, the record of Bristow and Ambo, who had been enslaved men, was not known.

By Tracey Wilson

More than 250 years ago, Bristow and Ambo, both enslaved men, served in the French and Indian Wars. When their service ended, they lived as veterans for many years in Farmington and then Hartford’s West Division – now West Hartford.

This recent discovery of their service from 1755 to 1761, through research done by the Stanley Whitman House in Farmington, and then incorporated into the research on slavery in West Hartford, helps us understand the power of their military service.

While some people of color were forced into military service, others took advantage of opportunities in the military. Armies needed soldiers, especially when quotas were established; men like Ambo and Bristow joined provincial regiments. Some served as volunteers and others as substitutes.

Bristow and Ambo’s service in this war was not about some big idea of freedom or equality, which could be argued about the American Revolution which soon followed. This war was over controlling land. For Ambo and Bristow, their participation was more about how it helped their own self-interest.

In their military service, Bristow and Amboy had the chance to travel, develop skills, and earn money. These types of opportunities were rare for enslaved men forced to live with those who enslaved them. A soldier’s life was not free, but it may have provided a positive change from the life of being enslaved in the West Division of Hartford.

Courtesy Tracey Wilson

At the same time, these men were not spared the horrors of war. The French and their Native allies fought hard against the British and the colonists. Ambo was injured at Fort Ticonderoga. Others were captured and enslaved by the French. Some were taken captive by the Indians.

When Bristow (1731-1814) entered the war, he was 25 years old. The first West Hartford record of Bristow is his 1775 manumission from slavery when he paid Thomas Hart Hooker for his freedom. The war records record his service 20 years earlier than his manumission. We can only speculate about where Bristow was born in Africa (noted on his gravestone), the age of his capture, his experience on the middle passage, and his probable stop in the West Indies. Perhaps he was trafficked by merchant Roger Hooker who took 11 trips to the West Indies before the Revolution. Roger Hooker was a step brother to Thomas Hart Hooker.

This military service predates his enslavement by Thomas Hart Hooker, who would have been just 10 years old when Bristow first marched with the militia.

Ambo (1714-1801) served in the war when he was in his 40s, alongside Bristow according to the muster rolls. He may have been born in Africa as well. He was enslaved by Josiah Hart in Farmington, the grandfather of Thomas Hart Hooker and Roger Hooker.

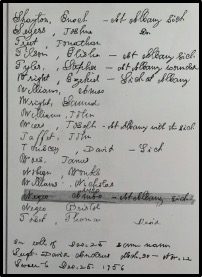

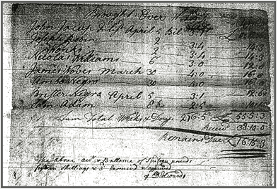

African American men like Bristow and Ambo were listed in the military ranks right next to white enlistees. They were not segregated like they were in the Civil War, World War I and World War II. They received the same pay as the white men of £4 per month. This pay helps explain how Bristow bought his freedom.

Courtesy Tracey Wilson

In 1756, Ambo is listed on a roll which shows that he was sick and in Albany. He recovered and remained in the service until 1761. Because he was older, he may have served more in a service capacity, perhaps cooking or taking care of supplies.

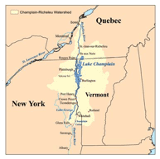

Both Bristow and Ambo served under Col. Phineas Lyman in the First Connecticut Regiment, mustered in 1757 for the war against the French and Indians in upstate New York and New France (Canada). Lyman hailed from Suffield and commanded a militia of 1,000 men. They participated in an expedition against Crown Point, at the south end of Lake Champlain, to push out the French. Though this expedition failed to wrest the port from the French, Lyman’s troops went on to win the Battle of Lake George and turn back the French and Indians.

Ambo and Bristow would have been part of the loss at Ticonderoga in 1758, also on Lake Champlain in the frontier between the British colony of New York and the French colony of New France. There were over 3,000 casualties in this battle, with the British and American colonial forces taking the brunt of this.

Bristow and Ambo were both enslaved men during their military service. They may have seen an opportunity for travel, for learning skills, and for being away from their enslavers.

Courtesy Tracey Wilson

Bristow bought his freedom from Thomas Hart Hooker in 1775, 17 years after his military service ended. Josiah Hart promised Ambo his freedom in his will. Hart died in January, 1758 while Ambo was still serving. Evidence from Farmington records shows Ambo getting two acres of land in Indian Neck along the Farmington River in 1758, probably through Josiah Hart’s will. In 1763, Ambo sold this land to Elijah Cowles, the uncle of Thomas Hart Hooker, signaling Ambo’s freedom.

Both men might have been promised freedom if they fought, and both might have gotten bonuses for serving. For these two men, the service seemed to provide them with experiences which helped them live as more autonomous and independent men in their later years. They were both freed, yet each stayed near those who enslaved them. The recognition of their deaths in the church records reinforces the concept that these were free men of some consequence, in part because of their military service.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Sources

- “Ambo Folder” Farmington Public Library, Local History Room

- https://sites.google.com/view/virtuallearningwitnessstones/home

- https://www.fortticonderoga.org/news/promise-and-prejudice-ticonderoga-and-the-unfinished-revolution/

- http://frenchandindianwar.info/lakegeorge.htm