College Bound: The One Big Beautiful Bill and Financial Aid

Audio By Carbonatix

Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

We-Ha.com will be publishing a series of essays/blogs/reflections on the issue of going to college – primarily a set of thoughts and musings, along with some practical advice, intended to support students and parents as they embark on this journey. While many of our readers are experts in this topic, many others are less knowledgeable and have little outside support. We hope this is helpful to all readers as they go through the various stages of getting into and getting something out of college.

Adrienne Leinwand Maslin. Courtesy photo

By Adrienne Leinwand Maslin

The One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) Act, which was signed into law by President Trump on July 4, 2025, contains many provisions that will affect higher education and that have an impact on college financial aid. Here are some highlights of the bill that both directly and indirectly affect higher education and what you can expect regarding financial aid for your own college education.

Depending on where you are in the college process – undergrad, graduate student, or still in high school – you will be impacted differently. Most changes to financial aid will occur on July 1, 2026 although some are being implemented immediately. It is always important to check with your own college’s financial aid office to understand how you will be impacted.

Pell Grants, one of the mainstays of financial aid, are still available but with some new regulations and eligibility conditions. The maximum Pell Grant will remain the same at $7,395 per year. But, under the new bill, “only students who have unmet financial need after grant aid from non-federal sources, such as states and higher education institutions, will be eligible for Pell grant funding.

Pell Grants can only be applied to direct costs like tuition, fees, and room and board – costs that are billed directly by a college. Other costs such as commuting costs, books, rent or food if living off-campus are no longer covered by Pell funding. There will also be a new Workforce Pell Grant program that will allow students attending short, career-oriented programs to be eligible for Pell Grants. This will allow a whole new group of students to be recipients of Pell funding and should be helpful to community colleges that offer these shorter certificate programs.

Another area of change to financial aid deals with Grad PLUS loans. These loans currently have no limit on the amount of money a graduate or professional student can borrow which allows such students to fully fund their education. Under the OBBB Act, Grad PLUS loans as well as Parent PLUS loans (which allow the parents of undergrad students to borrow unlimited amounts) will be capped. This may affect a student’s ability to pay for their entire academic program. Students in programs leading to professional degrees such as medicine or law may borrow up to $50,000 per year or $200,000 over their lifetimes. Grad students in non-professional programs may borrow up to $20,500 per year with a lifetime cap of $100,000.

According to Lending Tree, in 2018 tuition and fees at 70% of U.S. colleges and universities already exceeded borrowing caps for undergraduate students. This percentage has likely increased over the last seven years and given the OBBB, it will surely increase further. For many graduate and professional programs as well, these loan caps will not cover the cost of the full program and will require students to take out private loans or fund the remaining portion of their education via other means. Although it sounds crazy, another possibility is that colleges will lower tuition as they examine the ramifications of all aspects of the OBBB.

To further comply with the new law, college and university offices of institutional research will have to sharpen their pencils and conduct research on the earnings of their alumni. This is because, under the new law, colleges will have to determine whether the median salary of their alumni who graduated with degrees in particular subject areas are making more money than a working high school graduate who has not attended college. If program grads do not make more than a high school graduate in two out of three years, students in the program will not be eligible for federal student loans. For graduate programs, colleges will have to compare student earnings four years after enrollment with the earnings of working adults who only hold a bachelor’s degree and who are not enrolled in higher education.

Provisions of the OBBB also affect loan repayment plans. There are currently about seven repayment options but the new bill plans to eliminate most of them. As of July 1, 2026 students can opt for one of only two plans—a standard plan and an income driven plan.

The standard repayment plan will allow student loan borrowers to make fixed payments over the course of 10 to 25 years. … The Repayment Assistance Plan will allow borrowers to pay 1% to 10% of their income on a monthly basis, for up to 30 years. …

This exceeds the 20 or 25 year limit of current income-driven plans by five years and requires loan borrowers to be in repayment longer. As is currently the case, the student loan borrower’s remaining loan balance will be canceled after the repayment window ends.

The OBBB has changed the taxation formula on college endowments which will also have a bearing on financial aid for students. The current endowment tax law was enacted in 2018 and according to the law, private colleges with endowments that amount to $500,000 or more per full-time equivalent (FTE)* student should have their annual investment incomes taxed at a rate of 1.4 percent. Colleges with 500 students or fewer are exempt, as are institutions that educate most of their students outside the United States.

The new bill expands the tax based on the size of private institutions’ endowments and enrollment. Colleges whose endowments amount to between $500,000 and $750,000 per student will still be assessed a 1.4% tax. Colleges with endowments of $750,000 to $2 million per student will face a 4% tax, and those with endowments above $2 million per student will be taxed at 8%.

However, more small colleges are exempt from the tax, specifically wealthy institutions. Previously, only those colleges with enrollments of 500 students or less were exempt; now colleges with up to 3,000 students will be exempt.

The reason this affects financial aid is that many colleges use endowment funds to provide aid to students or to engage in tuition discounting. The endowment tax will obviously eat into an institution’s available funds and there will be fewer financial aid dollars to go around. Some students will receive less than they would have gotten in previous years and some may receive none at all. Each institution will determine how to spend the money it has.

Even aspects of the bill that are not directed towards higher education will impact higher education and the students who attend. For example, cuts to Medicaid, which will most likely come from state budgets, will result in a recalculation of those budgets as states attempt to deal with the shortfall. This could quite possibly mean less for higher education. And, as previously discussed, less money will be available for either need-based aid or merit-based aid as colleges use their funds in different ways, such as paying a higher endowment tax. Another possible outcome is that colleges may consider admitting more students who have the financial ability to pay their way. And, in an attempt to stay competitive, colleges and universities will likely try to develop new strategies for pricing.

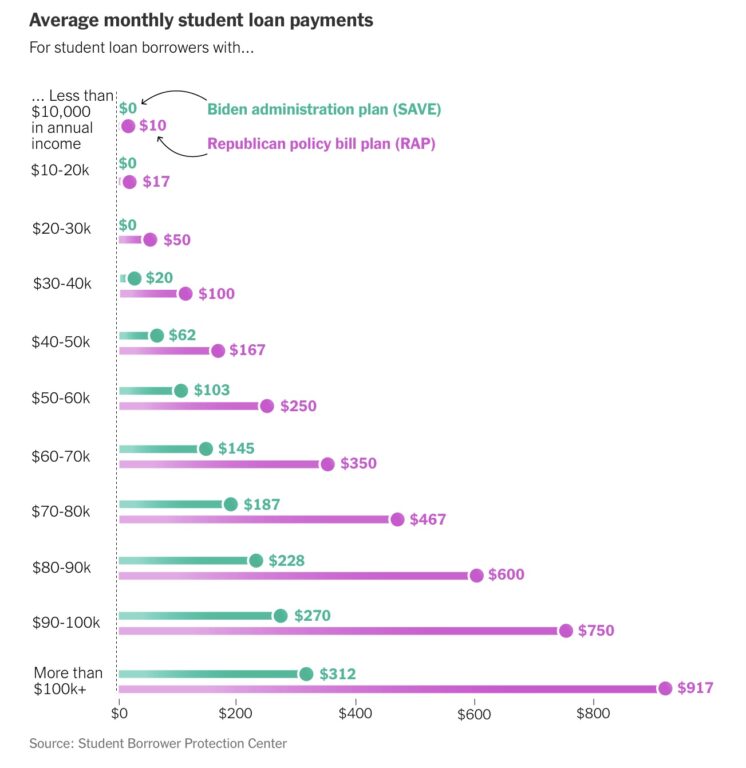

The changing college landscape, which to me feels like an avalanche, will also result in students reconsidering their options. The chart below from The New York Times shows how monthly loan repayments will balloon given a student’s income.

Screenshot

One final note: As you know, the Supreme Court recently approved the Trump administration’s plan to pursue mass layoffs at the Department of Education. This will certainly impact implementation of the new requirements of the OBBB Act. Remember the rollout of the new FAFSA two years ago? And that was with a fully staffed DOE! Higher education is clearly in a state of disruption on many fronts. I will keep you informed as I learn – and understand – more.

Adrienne Leinwand Maslin recently retired from a 45-year career in higher education administration. She has worked at public and private institutions, urban and rural, large and small, and two-year and four-year, and is Dean Emerita at CT State-Middlesex. She has held positions in admissions, affirmative action, president’s office, human resources, academic affairs, and student affairs. Adrienne has a BA from the University of Vermont, an MEd from Boston University, and a PhD from the University of Oregon. She is presently writing a series of graphic novels on life skills and social issues for 8-12 year olds believing that the more familiar youngsters are with important social issues the easier their transition to college and adulthood will be. Information about this series as well as contact information can be found at www.adrienneleinwandmaslin.com.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Good stuff. What a disaster Repubs are to eduction.