Commemorating Jude’s Declaration of Freedom 250 Years Later

Audio By Carbonatix

Jude was one of the formerly enslaved people who lived in West Hartford and is now memorialized with a Witness Stone. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

It’s been 250 years since Jude, formerly enslaved in West Hartford, declared his freedom, writes Town Historian Tracey Wilson as she looks to engage the community in local history along with looking ahead to the ‘Semiquincentennial – America250.’

By Tracey Wilson

On Aug. 6, 1774, Jude (1753–?) declared his freedom. He escaped from his enslavers Stephen Sedgwick, Jr. (1731–1792) and wife Lucy Woodford Sedgwick (1735–1787) on a Saturday night 250 years ago.

What did this declaration of freedom mean to Jude? To the Sedgwicks? To the community in which he was forced to live? And what does this mean for the beginnings of West Hartford’s commemoration of the semiquincentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1776? What stories can we tell of equality, freedom, and individual rights?

Slavery supported Connecticut’s economy in the 18th century, based on agriculture, maritime trades, and skilled crafts. Connecticut merchants like West Hartford’s John Whiting traded in networks in the Caribbean. They exported sheep, horses, wood, and onions produced by enslaved labor, and in return, imported sugar, molasses, and other commodities.

Within this complex economic landscape, the story of Jude, who declared his freedom from his enslavers Stephen and Lucy Sedgwick, Jr., emerges as a significant act of defiance. Jude’s escape was not just a personal quest for liberty but it also challenged the economic and social structures that benefited from slavery.

As we commemorate 250 years since Jude’s declaration, it is essential to recognize this broader economic context of slavery in Connecticut and its ties to the Caribbean trade. Jude’s actions and his pursuit of freedom, make his story an essential part of our historical understanding.

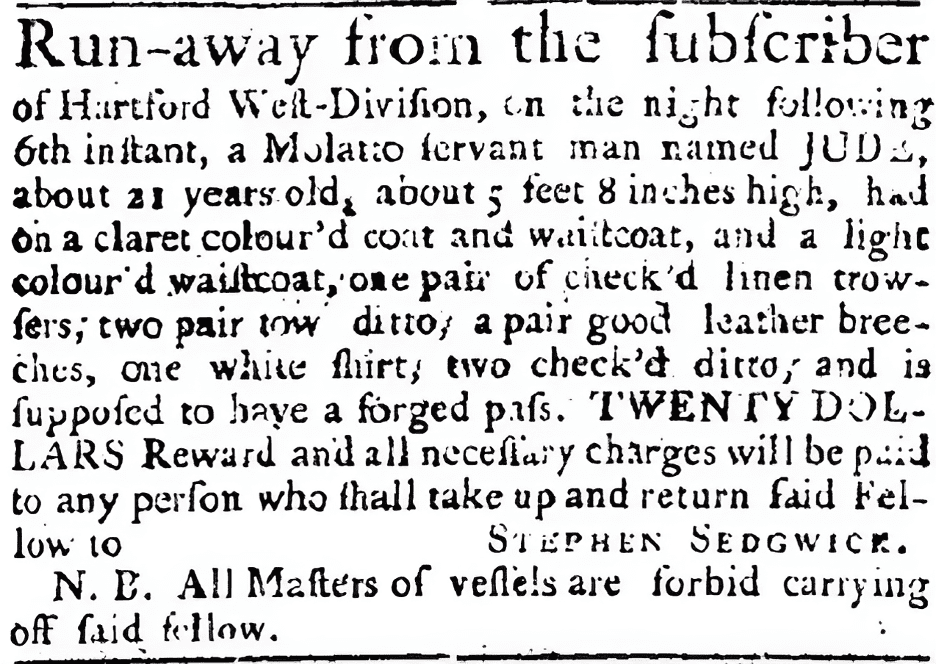

From the Connecticut Courant, Aug. 9, 1774. Courtesy of Tracey Wilson

The advertisement for Jude speaks of a man with a plan. This does not seem like some rash decision thought up on August 5, but more of a concerted effort planned for weeks – maybe months – maybe years, that he carried out on that Saturday night.

The first extant evidence of Jude exists because his enslaver, Stephen Sedgwick, Sr., died in 1766. Jude, at 13 years old, was appraised in Sedgwick’s inventory as “a negro boy 45 pounds,” listed next to “part of a cyder mill 7.” The inventory also lists a “negro bed and furniture.”

Sedgwick, Sr. willed Jude to Stephen Sedgwick, Jr., his 35-year-old farmer son who inherited 140 acres of farmland, meadow, orchard, and woodland in the area from today’s Cornerstone Pool to Spicebush Swamp, west of Mountain Road. At that time, this land was within the border of Farmington.

Jude most likely would have known his new enslaver, his wife, and their two young children. He probably carried on with much the same work as he was forced to do before. And, as he grew into adulthood, surely he took on new tasks. The same inventory gives us a clue to what that work might have been. The appraisers listed two yokes of oxen, 51 sheep, 12 cows, a bull, 12 loads of hay, a plow, a cart, a dung shovel, pitchforks, 11 yards of worsted yarn, and a dyeing tub. The appraisers, Noah Webster, Sr., the Rev. Benjamin Colton (also an enslaver), and Charles Seymour were complicit in the institution of slavery when they set a value to this 13-year-old boy.

Eight years later, Jude declared his freedom. The Connecticut Courant’s advertisement read that Jude was “mulatto” – today we would use the term biracial. We can only speculate on who his parents were, knowing that he had a Black mother and a white father. Slavery was determined by the mother by custom and law. Who was Jude’s father? Did Stephen Sedgwick, Sr. enslave his mother?

Being biracial was not unusual. In that same year of 1753, Lemuel Haynes was born in the West Division to a white mother and a Black father who was enslaved. At five months, Haynes was indentured until he was 21 to a minister’s family in Granville, Massachusetts. At age 21, when Jude escaped slavery, Lemuel Haynes became a free man, released from his indenture. He was the first Black man to be ordained a minister in the United States and has a historical marker in front of the First Church in the center of town.

It is likely that Jude knew Bristow, born in Africa in 1731 and enslaved by Thomas Hart and Sarah Whitman Hooker in 1774. He may have known the couple Coffy (c. 1690–1778) and Sarah Coffee (1686–1783), probably born in Africa, and enslaved by Dr. Daniel and Mary Sedgwick Hooker – an aunt to Stephen Sedgwick. When Jude was 13, Sarah was 80. Sarah and Bristow would have held special status in the community because of their birthplace, their expertise, and their longevity

Bristow bought his freedom, owned land, and had expertise as a farmer. Sarah may have been a midwife, working with Dr. Daniel Hooker, Jr., and Dr. Daniel Hooker III, who lived on North Main Street. Might they have encouraged Jude to seek his freedom?

Jude made a plan. He chose to run on a Saturday night, knowing that Sunday was a day of rest, knowing that night, when all were asleep, was a good time to get moving. He ran on the night of a new moon, reducing the amount of light in the night sky. He ran at harvest time, when crops in the field may have been available to him.

Jude took clothing with him – a red coat, two vests, three pairs of trousers, one pair of leather breeches, and three shirts. He thought his escape would be successful.

Jude had a plan. He carried a forged pass. According to law, any enslaved person who was traveling alone had to carry a pass. A person who was free also needed to carry papers to make the case that they were free. Where did Jude get his pass? Could he write? Did he have an accomplice? And how did Stephen Sedgwick, Jr. know that he had this pass? Did someone tell Sedgwick of Jude’s plan?

Stephen Sedgwick, Jr. offered a twenty-dollar reward for finding Jude. This turned every citizen in the area into an arm of the law who could enforce the system of slavery. Today that reward would be about $800, enough to motivate many people to look.

Finally, the N.B. (nota bene, meaning “note well”) relates that captains of ships were forbidden to take Jude onto their vessel. This statement is evidence that “masters of vessels” did take freedom seekers onto their ships. Captains always had a need for sailors, and Black sailors made up as much as a quarter of the workforce on these ships.

Jude’s forced work for Sedgwick may have taken him to the seaport in Hartford. He may have known when sailing ships arrived – and the six miles from Sedgwick’s property to the river could have been covered in one night.

Jude’s freedom-seeking ad appeared three times in the Connecticut Courant. Was he successful? No other documents about him have been found.

We do know, in the age of Revolution, that he had heard the words of liberty and freedom.

On May 19, 1774, a Farmington gathering of as many as 1,000 people, including Sons of Liberty, protested the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston to most trade as a result of the Boston Tea Party. A handbill in Farmington asked its citizens to “honor the immortal Goddess of Liberty.” They burned a copy of the Port Act. They resolved that “the present Ministry … has a design to take away our liberties and properties and to enslave us forever … Do thou great LIBERTY inspire our souls! And make our lives in thy possession happy!”

People who enslaved others supported these protests. Paradoxically, these protestors’ words would have resonated with Jude, and likely he would have heard men discussing these ideas, or possibly he even attended this protest.

Jude’s declaration of freedom came almost two years before the Declaration of Independence. His inspiration to seek freedom came from the unjust and cruel institution of slavery. And his motivation could have been enhanced by the growing rhetoric of freedom among colonists rejecting the control of the British. His story is an integral part of understanding what freedom means.

Jude’s declaration of freedom reminds us of the enduring struggle for liberty and justice … for all. Our community has the chance to reflect on our history and its implications for today as we approach the Semiquincentennial of the Declaration of Independence

Join us in a commemoration of diverse stories that shape our past. These narratives help to better understand the present and contribute to a future where freedom and equality may be realized for all. Raising up those whose names have been lost to history is an important aspect of this 2026 commemoration.

Our America250 commemoration strives to tell inclusive stories on a local level, engage the community in doing history, and encourage civic engagement. If you are interested in being involved in the town’s commemoration, contact Town Historian Tracey Wilson at [email protected].

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.