From the West Hartford Archives: 1856 in West Hartford

Audio By Carbonatix

Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The featured photograph was apparently taken in 1856, according to William Hall’s “West Hartford,” showing the southwest corner of South Main Street and Farmington Avenue. In reality, this probably was taken in the 1870s. Leonard Buckland’s store was built previously, but this kind of architecture pictured would be very uncommon in the 1850s.

Nonetheless, we can travel back in time to 1856, a tumultuous year both in U.S. history and local history. It was a year that was deeply connected to pre-Civil War politics, the rise of agricultural modernization, and expansion of community identity. Two years after the town was granted independence from the City of Hartford, West Hartford’s history was shaped by the forces of religion, political hatred, and westward expansion.

On Saturday night, Jan. 5, 1856, a great snowstorm hit the Hartford area into the following Sunday morning. The trains were stopped completely (the railroad had been through Elmwood at New Britain Avenue to Newington a little over a decade ago) and the mail messengers traveling from Plainville spent almost three hours just getting from West Hartford to Hartford.

Ironically, despite the town’s independence in 1854, West Hartford was becoming more connected to the city it broke from. A year before, William H. Seymour took over Frederick Brace’s omnibus line, an early form of public transit. It was essentially a scheduled stagecoach service operating along Farmington Avenue, a direct ancestor of the modern city bus system. This large, horse-drawn enclosed coach was designed to carry 10-20 passengers along the route into and out of the city. When Brace opened the line in 1854, it left West Hartford Center at 6:15 a.m., 11:15 a.m., and 4 p.m., and back from Hartford at 9 a.m., 1 p.m., and 6:15 p.m.; of course, there were some late-night exceptions for some evening spectacles.

Not long after Seymour took over the omnibus line, a fellow farmer down the road from him, Joseph Davenport, penned a letter to the Hartford Courant office. He noted that while he did not originally support the independence of West Hartford, he had come around to the idea once it was set in motion. He cited Seymour’s omnibus line in the fall of 1855 as an example of West Hartford’s economic independence and actually encouraged city folks to move out to the country. He depicted Hartford as overcrowded, confining, and unnatural to live in, pushing people to move into a town he loved. The omnibus line was the infrastructure that proved that West Hartford could not only take care of itself but also advertise itself to the people moving out to distant farmland. After the Civil War, this movement would surge, especially in the east end of town. For now, West Hartford Center remained the beacon of hope for all those city dwellers longing to move somewhere quiet.

West Hartford was also a leader in the rural economy through its position in regional agriculture and horticulture. The town in 1856 was a highly organized agricultural community with deep ties to Hartford and a regional reputation for expertise in livestock, fruit, and dairy. The Hartford County Agricultural Society, which hosted the annual county fairs, listed West Hartford men on the judging committees: Morgan Goodwin, Benjamin Belden, Augustus Hamilton, Lyman Hotchkiss, Jr., Samuel Hurlbut, Emerson A. Whiting, John Whitman, and many more.

At these exhibitions, people like Charles S. Mason, who lived on South Main Street, would come with huge varieties of products to display. At a horticultural exhibition held by the county in August 1856, Mason brought eight varieties of seedling petunias, which the Courant referred to as “very fine.” But this was just the beginning. In October, the annual State Fair was held in New Haven over the course of several days. Allen S. Griswold, Benedict Hamilton, Lyman Hotchkiss, and others showed off their horses, their working oxen teams, bushels of oats, Durham calves, collections of apples, peaches, pears, turnips, grapes, and potatoes. Lyman Hotchkiss consistently won awards through the 1850s for his quality honey. Augustus Hamilton won second best at the plowing match. This type of event was competitive and involved farmers demonstrating their skills in guiding a plow and team (usually oxen) across a plot of ground, judged on their technique and team management. Speed was not the main goal; quality of work mattered far more.

By far, the State Fair was one of the most important social and economic occasions of the entire year, bringing together thousands of people in otherwise isolated towns. West Hartford was a center of nurseries (like Steele’s Nursery or Harvey Rice’s small operation), fruit-stock trade, and celebrated varieties like the Hartford Prolific Grape, grown on Albany Avenue. Orchards were plentiful and larger businesses, like Paphro Steele’s, could develop a deep scientific interest in horticulture.

Indeed, as cities like Hartford dove into early industrialization, farming towns like West Hartford could experiment with agricultural storage, preservation, and grafting. The annual state fairs could show off their progress in techniques. They were also a chance for the work of men and women to be shown together. In years past, Mrs. Samuel Hurlbut displayed a beautiful bedspread; Mrs. Joseph Davenport showed her sewing and raw silk; Sophia Whiting showed off her embroidery; and Mrs. William Storer brought three custard squashes and homemade blankets.

Women’s participation in the fairs was one of the few socially accepted public arenas in which women could outwardly show skill, gain recognition, and contribute visibly to the community prestige. Typical of standards in the 19th century, this did not erase gender inequality but created a sanctioned parallel sphere of accomplishment that could present a united front, especially for West Hartford as a whole. The women who participated in the 1850s were later organizers against alcohol, church society leaders, school board advocates, and early suffragists. 1856 was one of the years that would serve as subtle training for the post-Civil War social movements.

1856 was a big year for tobacco management and paved the way for future changes. Tobacco was a huge business in the Connecticut River Valley, but growers in West Hartford were struggling with price volatility, dependence on speculators, lack of storage, and disorganization. Before the 1840s, tobacco as a crop was sustainable because it was sold within the local community; by the 1850s though, it was an immense export to Europe, as the Connecticut Valley tobacco leaf was ideal for European cigar wrapping.

In the first two weeks of 1856, West Hartford residents Benjamin Gilbert and Walter Cadwell attended the Tobacco Growers’ Convention in Hartford and endorsed the concept of tobacco warehouses. It seems like common sense, but the tobacco warehouse centralized storage, forced middlemen to respond to publicly posted prices, and kept product in good condition over a longer period of time. The warehouse movement normalized the idea that farmers had shared interests and that they could collectively manage risk by joining forces against the speculators, who used to buy the raw product cheaply right after harvest and then profit from the price swings.

More importantly, West Hartford’s involvement in this movement anticipated the rise of farmer cooperatives that would go on to change U.S. history. The Grange was founded 10 years later and the Populist movement of the 1890s helped spur many of the reforms that still exist today. West Hartford was at the forefront of larger American agricultural trends that can be found in any textbook.

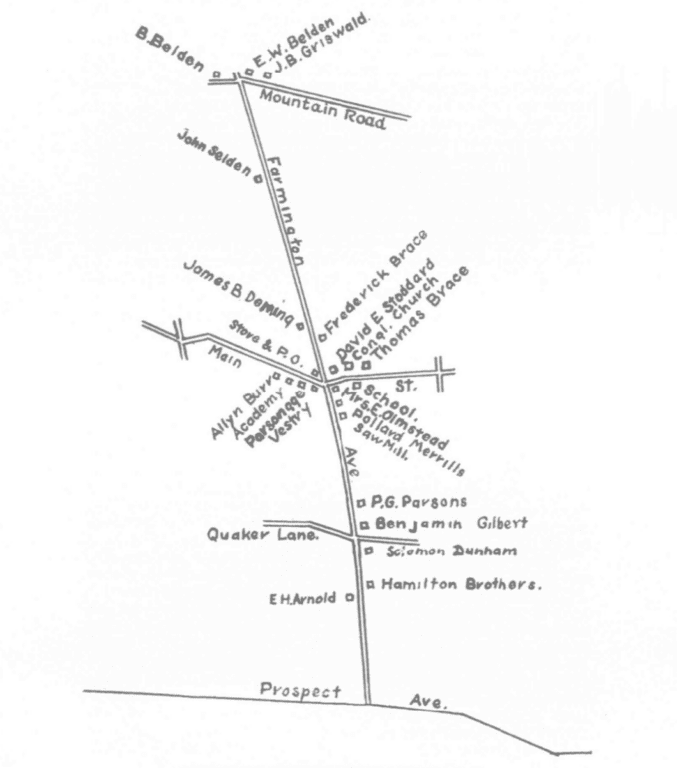

Farmington Avenue in 1854, including influential citizens mentioned here. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

1856 is also exciting for another reason beyond the farmland and burgeoning labor movement. West Hartford dove headfirst into the political crises of the years before the Civil War and it was ugly. In the early 1840s, the U.S. still worked under two parties: the Democratic Party (strongest in the South and generally sympathetic to slaveholding interests and anti-bank sentiment) and the Whig Party (strongest in New England and favored economic modernization). This system worked as long as slavery seemed containable. But several national events destabilized the political system.

The annexation of Texas in 1845 and the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848 reopened the central question of whether new territories to the U.S. would be free or slave states. The Compromise of 1850 attempted to stabilize the situation by admitting California as a free state, letting Utah and New Mexico vote on the slavery question, abolishing the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and passing the Fugitive Slave Act. The idea that free states in the North would have to return escaped slaves to the South helped fracture the Whig party into those in the North against slavery and those in the South in favor of it.

By the early 1850s, the Whig party effectively collapsed and was replaced by smaller parties that collaborated against the Democratic Party. In 1855, Edward Stanley was elected as the first independent Representative from West Hartford (just 10 months after independence); he was under the banner of the former Whigs and the so-called Know-Nothing Party, which was heavily anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic. This wasn’t too surprising considering Irish immigration to Hartford was surging. The political fragmentation of 1854-1855 set the stage for the 1856 presidential election and in West Hartford, it was an ugly one.

On March 10, 1856, an informal convention was held at the West Hartford meetinghouse by all those who were “opposed to the present National Administration,” meaning the Democratic President Franklin Pierce. West Hartford Whigs believed the president was a willing tool of the so-called “Slave Power,” a conspiracy of Southern slaveholding elites who dominated Washington politics. As president from 1853 onward, he pressured into existence the act that would singlehandedly radicalize West Hartford: the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act. It repealed the Missouri Compromise line (which had restricted slavery’s expansion since 1820) and introduced popular sovereignty, meaning settlers of western territories could vote slavery up or down without the federal government getting involved.

To West Hartford, this made him one of the chief political villains of the decade and it shows in their response to the crisis brewing in Kansas. Since the act meant that residents of a territory like Kansas could decide by vote whether to allow slavery, both sides of the debate rushed supporters into the territory to influence the outcome, leading to fraudulent elections, rival governments, and brutal violence. Raids, arson, guerrilla warfare, and retaliatory killings became common in Kansas in the years following 1854.

As news of the so-called “Bleeding Kansas” crisis reached Connecticut, some West Hartford residents jumped into action. Harvey Rice, who owned a 26-acre farm near South Main Street and New Britain Avenue, sold all of his belongings in the spring of 1856 and moved to Kansas to settle the territory and represent the Free Soil movement against the expansion of slavery. When he came back in the summer to officially bring his family out west with him, he had many stories to tell of the “oppressions” he saw. The Hartford Courant reported in June: “Even Hartford, including West Hartford, have quite a strong representation in that beautiful but now barbarous land.” Families entered the national conflict as a result and opinions hardened against the Democratic administration that supported the “Slaveocracy.”

The Whig Party had been replaced by an opposition split between the Know-Nothings and the newfound Republican Party, which had formed nationally in 1854 in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. When Connecticut elections were held in April 1856, West Hartford votes were split among the different opposition groups that had not yet united and therefore William Sedgwick, a Democrat, won the legislative seat from West Hartford. In a town that voted majority anti-Democrat, they had let the united Democratic candidate Sedgwick take power. People were furious and vowed never to let that happen again.

As the 1856 presidential election campaign heated up, the so-called opposition movement in West Hartford took clear steps to unite the different parties. In the late summer, residents organized a Fremont Club in support of John C. Fremont, the Republican presidential candidate. On Aug. 14, 1856, the Courant noted: “The people of West Hartford are getting somewhat aroused to the political condition of the country, and are putting on their armor for the fight for freedom … The sober and substantial electors of this agricultural community are determined to lay aside and forget all their former political differences, in view of the importance of the present struggle.”

Weekly meetings were held by the Fremont Club, supplied by late-night trips on the omnibus and speeches by major political figures in the Hartford area. The tone was increasingly unified and militant, defining the upcoming election as a battle for freedom, a struggle against slavery, a defense of Kansas, and a total rejection of the “Shamocratic” administration.

Politics in West Hartford shifted from economic concerns to moral radicalism. Residents increasingly understood themselves not as voters but as participants in a moral crisis surrounding the expansion of slavery and the administration they hated with a passion. The members of the Fremont Club organized a Kansas Relief Association in September 1856 to solicit contributions for activism out west. Anti-slavery meetings were held weekly into October until 11 p.m., ignoring the church bells and apparently “converting” former Democrats. The rhetoric was fiery and accusatory. H. Clay Trumbull of Hartford addressed the crowd in West Hartford and the Hartford Courant wrote: “We cannot conceive how it is possible for any member of the Democratic party to listen to his remarks, and continue to act with those who have been instrumental in selling the party to the Slaveocracy, with as little ceremony as one slaveholder transfers his human chattel to another.”

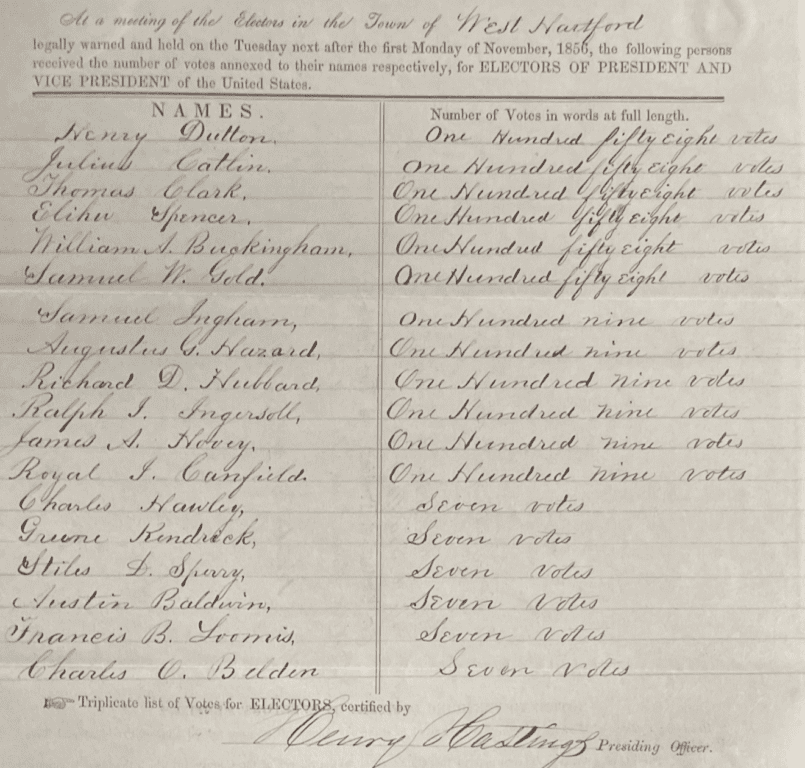

On Oct. 6, 1856, West Hartford held its town elections and voted in the entire Fremont ticket. The town had a disorganized opposition in April, but in six months, the anti-slavery coalition consolidated completely under the Republican umbrella. When the presidential election was held on Nov. 4, West Hartford voted 158-109 for Fremont over James Buchanan. An additional 7 voted for Fillmore of the American Party. Of course, anyone who knows their history knows that the Democratic candidate James Buchanan won the election nationwide and went down as the administration that accelerated the crisis that led to the Civil War. Less than six months later, the Buchanan administration lobbied the Supreme Court to issue the Dred Scott decision, which declared that black people were not citizens and destroyed any hope for compromise.

West Hartford would begin preparing the local political movement that would ultimately elect Abraham Lincoln into office.

List of electors and their pledged votes in the 1856 presidential election, from the archives of the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Behind the political, moral, and economic crises of the day, West Hartford had a highly organized Protestant civic-religious culture with strong engagement in education and reform. The 1830s had seen the last wave of religious revivals, part of the broader Second Great Awakening. West Hartford held huge revival meetings before and after their longtime pastor Rev. Nathan Perkins (who had served the Congregational Church since 1772!) died in 1838. By the 1840s, an evangelical consensus dominated American public life, especially in the Northeast, and it fostered multiple movements that would evolve through the years: women’s rights, abolitionism, temperance (anti-alcohol), and utopian ideology.

By 1856, religion had become thoroughly entangled with moral reform and politics, focusing on slavery, the nation’s moral degradation, fear of Catholic immigration (the Irish settlements in the west end of Hartford did not help sentiment), and biblically informed citizenship. At a Fourth of July celebration in our town, the parents congregated at the vestry and marched into the meetinghouse, where the Declaration of Independence was read and the choir sang songs. The concluding address by Rev. George Wood made it clear that the next battlefield was morality and civic responsibility. The audience was told to “give themselves to the contest” in the coming moral battles. Teachers, families, and later college graduates (like George Talcott, who graduated from Yale in 1855) were fully cognizant that America was on the edge of violent conflict over slavery, nativism, militant religious movements, party and mob violence, and the looming political strife.

Talcott, as a senior from Yale, gave the concluding oration at the graduation exercises on the topic of the moral crisis with respect to religion. Questions of slavery, personal virtue, duty, and social decay were everywhere, and educated elites, even from the farms of West Hartford, believed that moral failure would lead to national collapse.

The Second Great Awakening strengthened other denominations, which allowed the Episcopal Church (St. James’s) and the Baptist Church to build communities in West Hartford Center from 1853 to 1858. West Hartford’s proximity to Hartford, a growing urban center, was key to the flourishing of different religious movements and the idea that they could coexist within the same space.

It is easy to see a year like 1856 and envision a farm town like West Hartford trudging along, day by day, without appreciating the richness of this era. Two years after the independence from Hartford, this town was no longer culturally uniform and was participating in regional and national conversations with an intense energy. It was transitioning from an old Puritan community into a more diverse, mobile, and suburbanizing one. Agriculture remained the backbone of this town, but the community was experimenting and training in collective action at a grander scale than previously contemplated. The political consolidation would be felt for the next hundred years and civic participation surged. If West Hartford was a quiet farming village before independence, it was clear that after 1856, it would never be the same.

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Thank you, Jeff Murphy – what a great article. Highly interesting, provocative and so well researched. Love learning about West Hartford’s ancestors.