From the West Hartford Archives: Annexation Special Election

Audio By Carbonatix

Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

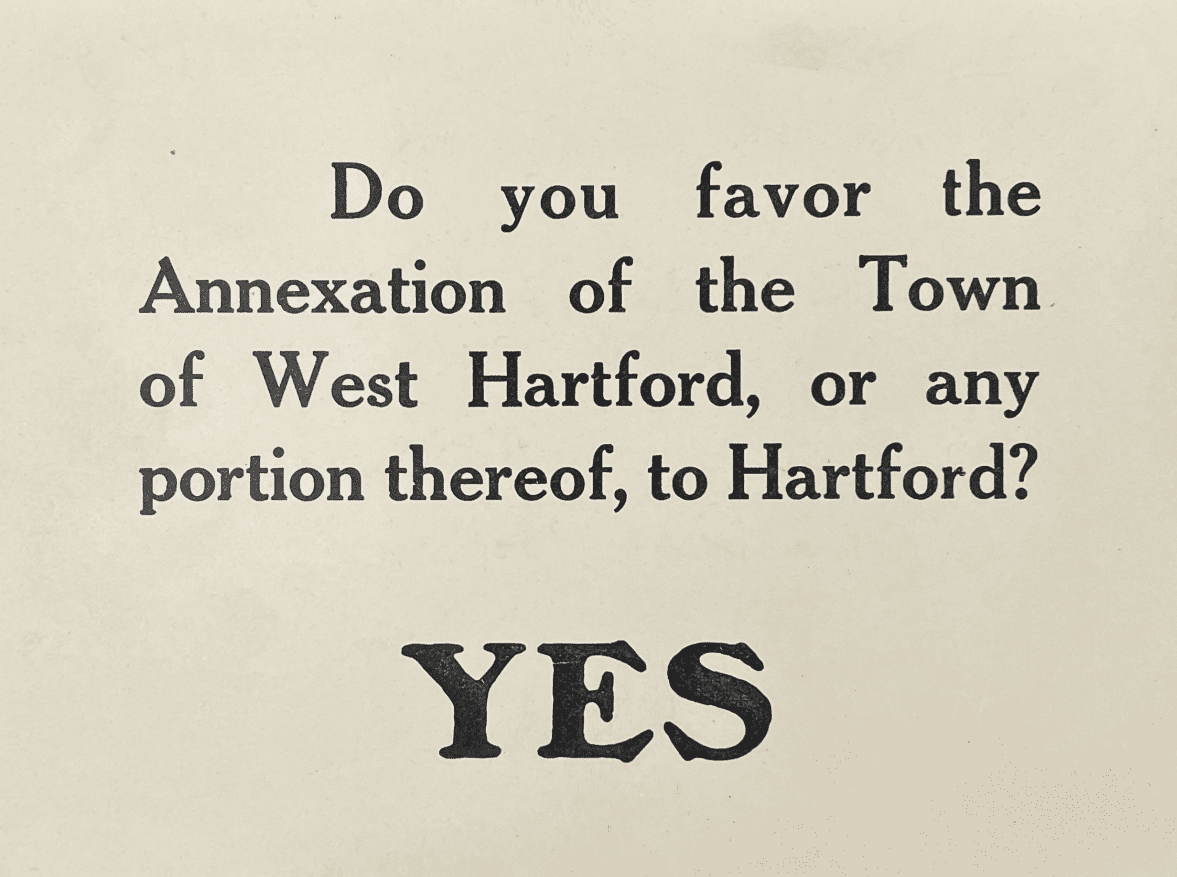

This may seem like a ridiculous question at an election, but this is a ballot found recently in the archives of the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society, dating back to the 1924 annexation vote.

Since West Hartford became independent from the City of Hartford in 1854, there have been multiple efforts to form a movement to reunite the two into a “Greater Hartford.”

The first serious effort in 1895 was driven by political complaints by some residents in the wealthy east end that they were paying the majority of the taxes for the town without the advantages of a city. The petition to annex the east end of West Hartford failed to garner enough signatures that year, but in a way, it was the furthest the movement came to gaining enough steam.

After that, the dream of a Greater Hartford metropolitan area continued. In 1904, East Hartford residents pushed for annexation after the Bulkeley Bridge was started across the Connecticut River, sparking fears that the same agitation would arise over here. A few years later, the Mayor of Hartford gave an interview, plainly stating that the expansion of the city meant that there could be a serious effort to pursue the annexation of the surrounding towns, like West Hartford, Wethersfield, and Windsor.

By 1910, influential residents were pushing for the towns to be merged in order to synergize business interests. Frederick Rockwell, who developed the Boulevard fifteen years prior, began organizing for a special town meeting to consider petitioning the General Assembly the annex the entire town to Hartford. The Hartford Courant reported on Dec. 10, 1910 though: “From inquiries made in West Hartford yesterday, it seemed that the sentiment is against such wholesale fusion at present, although it is far from unanimously so.”

Some of the same residents who had opposed annexation in 1895, arguing that it was a bogus political movement by whiny taxpayers upset that they were living in the country without the benefits of city life, argued in 1910 that the town had grown in a way that made annexation inevitable. In fact, ironically, the arguments made by the “East Enders” in 1895 were made obsolete with the growth of the town: the lack of police and fire protection, unsuitable water provisions, and inadequate schools of the past were replaced by an improved system of governmental organization.

Now, Fred Rockwell was focusing on the alignment in business interests, especially carfare and regulations for tradesmen. Other wealthy residents in town, like Stewart Dunning, simply stated that as much as Hartford wanted to consume the surrounding towns, they would not want to actually take responsibility for maintenance of the 75 miles of streets and the school system to accommodate the thousands of new residents. The selectmen met a few days later to appease the burgeoning movement, but they were categorically opposed.

When the special town meeting convened on Dec. 16, 1910, the Courant reported the anger and condescension in the opinions of those recorded. Adolph Sternberg said, “When I saw it in the paper, I thought I was having a bad dream.” Charles Hall remarked that it was “an insult to the town to say that they were on the lower rung of the ladder.” Frederick Duffy, who had moved to West Hartford when he considered it “God’s country,” called for three cheers for the “town of West Hartford”, which was seconded. Rockwell was advised to “be quiet. Go home. Think about it.”

The sentiment for annexation continued through 1911 and 1912 across central Connecticut, but it was not seriously considered by the town. Any new mention of it brought mentions of the “debate” roaring back, but it was all fodder for tax arguments, complaints about dwindling real estate and infrastructure, and ugly discussions about the relationship between the town and the city. People like Sternberg shot back that Hartford was full of “bad influences” and that if anything, West Hartford should annex the city!

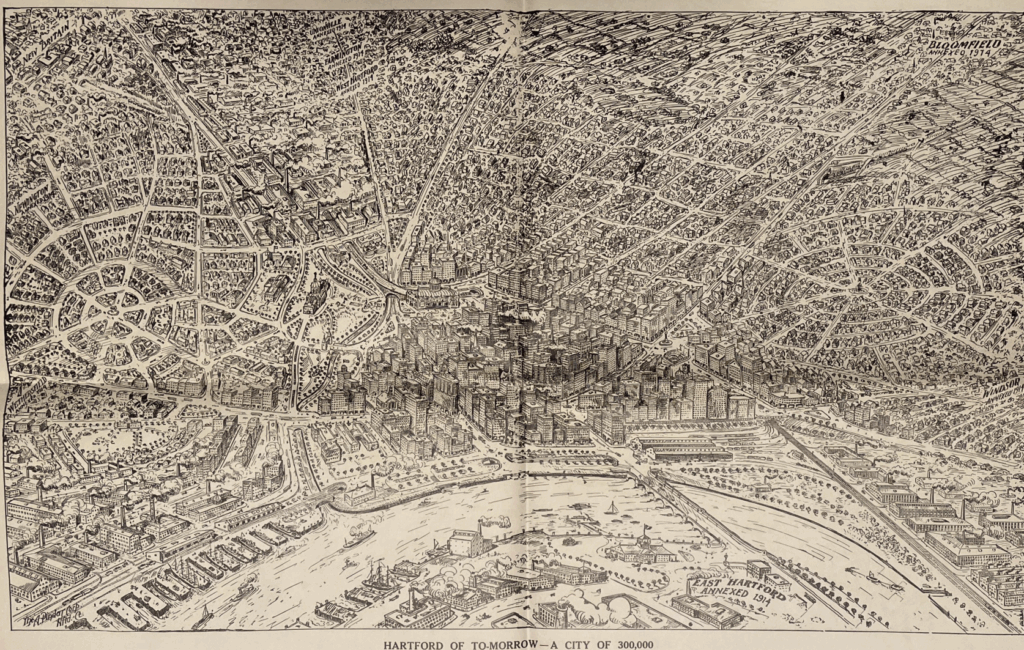

Greater Hartford map showing West Hartford’s eventual annexation (top center-left). From the 12th annual banquet of the Hartford Business Men’s Association at the Allyn House.

Another decade went by without much chatter. World War I took over the conversation and when the boys came back home from Europe in 1918 and 1919, labor instability and social unrest made headlines for months. As things settled down after the war and West Hartford transitioned its town government to the modern form we use today (Council-Manager), this town became fertile ground for yet another attempt at annexation to the city.

In the early 1920s, the idea of a “Greater Hartford” was revived and began appearing in numerous newspaper ads and political speeches. In mid-June 1922, Secretary William L. Mead of the Hartford Chamber of Commerce was quoted: “The Greater Hartford should be the next achievement of our organization and the first step ought to be the annexation … the reclamation of that part of West Hartford located between Prospect Avenue and the crest of Vanderbilt Hill.” He cited Hartford business officials who lived in town: the president of Travelers, the chairman of the board of Hartford Fire Insurance, vice president of the Aetna, numerous banking officials, officers at the Colt factory and typewriter companies, and retired merchants. They “live just over the line, but [their] interests and efforts are all Hartford’s.” The perception was that these businessmen (and the appeal to authority almost always trended male) were simply living in West Hartford but considered themselves to belong to the city.

The effort in the early 1920s was a more formalized version of the events that took place a decade before and was the product of the era that came before it.

By the early 20th century, many American cities were experimenting with reforms aimed at improving efficiency, reducing corruption, and modernizing governance. West Hartford moved to a Council-Manager form from the old selectmen model in 1919. For larger cities, one major idea for reform to accomplish this modern form of government was simply municipal consolidation: the absorption of smaller towns or suburbs into a central city to streamline services and strengthen central planning.

Hartford was a wealthy insurance and manufacturing hub for decades by this point, but by the 1920s, suburban growth was spilling over into nearby towns. Some city officials feared “tax base flight” as wealthier residents moved beyond Hartford’s jurisdiction to carry the costs of services and infrastructure to what they considered a “poorer” town, both in economics and in people. Consolidation was a way to retain economic strength and political influence.

The Greater Hartford model, to people like William Mead, was inevitable and natural. “The local pride of the smaller communities should not stand in the way of what would be a natural growth,” he said that summer. He argued that Hartford had grown its population 40% for three decades and was trapped by the Connecticut River, so it now needed to acquire territory. “Hartford must soon take steps to acquire what already is for all practical purposes a part of the city.”

Notably, the city of Berlin, Germany had done the same thing just a few years before, passing their Greater Berlin Act to annex dozens of surrounding towns and rural areas into the new metropolitan Berlin. Flavors of modern governance played out across the world in the 1920s. Prussian nation-building and the rise of Italian fascism emphasized central control and efficiency by consolidating smaller towns. Authoritarian regimes broken by World War I used state power and ideology to accomplish this organization; across the pond, the push for a modern urban Hartford came from local elites and business interests looking to align. In a way, the push for reform masked another layer of this movement: to reshape government to make democracy more business-friendly.

Like the annexation debate before it, some of the residents who opposed it in 1910 considered it in 1922. Charles Hall, who called Rockwell’s annexation plan an “insult,” turned around and called for it to be worth considering; of course, by that point, he was chairman of the town’s tax assessment commission.

The town council was still relatively new and the different boards bickered and tattled on each other constantly. Some residents were consistent: William Hall, who had been viciously opposed in 1895 and 1910, immediately looked to explain the root cause and hopefully shut it down. Economic problems, to him, were the root issue: overpopulation, lack of adequate middle and high schools, and a fresh form of government had agitated the people in the wealthy east side of town to push for annexation. Real estate developers tapped into the sentiment too, capitalizing on the debate.

In the fall of 1922, John Linskey, who had laid out the streets off Brace Road in the Center, advertised his Westlawn tract as “planned for one of the finest residential suburbs in Greater Hartford.” The language oozes with hints of annexation, even if it’s just to drum up hype: “Westward the great tide of Hartford’s tremendous growth takes its way.” West Hartford was an independent town for almost 70 years by that point, but it made sense to capitalize on the idea that people were just happening to spill over into our little community.

By the start of 1924, the Hartford Chamber of Commerce approved a report on annexing West Hartford, endorsing the idea of petitioning the General Assembly. Unfortunately, they did this without first consulting with the City of Hartford, which angered both Hartford Mayor Kinsella and the townspeople in West Hartford. Kinsella emphatically rejected the idea, leaning on the fact that West Hartford was slowly solving the economic problems that had perhaps fueled the flames of annexation talk a few years before.

Politicians in West Hartford argued that the annexation talk was all about gerrymandering and unfair political maneuvering. Candidates in the 1924 election branded themselves as pro- or anti-annexation. A special election was called within West Hartford for the end of 1924, with a mass meeting (and a raucous one) hosted by the Chamber of Commerce on the eve of the vote. “Not a word was spoken in favor of annexation” at the meeting.

In town, political parties lobbed annexation accusations at each other, meaning that no one felt particularly interested in throwing their weight behind something so divisive. Despite all the debate, when the election was held on Dec. 16, 1924, less than half of the registered voters showed up. By a vote of 2,119 to 631, the proposal of annexation to Hartford was swiftly defeated.

Efforts continued behind the scenes to drum up energy for a petition to the General Assembly in 1925 (and some in Hartford argued that West Hartford’s special election was “hurried and irregular”), but overwhelming opposition silenced any new members to the cause by 1926. Suburban resistance hardened and the Great Depression a few years later further killed momentum as cities and towns looked inward. More than a century later, could this debate ever return?

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.