From the West Hartford Archives: A&P Store and Elmwood Hardware, Newington Road

Audio By Carbonatix

A&P and Elmwood Hardware at the corner of New Britain Avenue and Newington Road. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

When the Sears home was torn down at the southeast corner of Newington Road and New Britain Avenue, it was replaced by a corner store occupied by the A&P Company and the Elmwood Hardware Company in 1948, built by the Kamson Company of White Plains, New York.

The first notice of this store was the liquor permit applied for by James J. Hadley of Bonner Street in Hartford, who was designated the permittee and owner. The A&P opened its doors here on June 24, 1948 as the “Store of Tomorrow,” one of the first modern supermarkets to hit the streets of Elmwood.

There had been an Italian meat market further west along New Britain Avenue and the village had a general grocery market in an old house east of Woodlawn Street, but at the A&P at 1099 New Britain Avenue, more than 3,000 different food items were displayed in 8 departments: the Jane Parker Bakery, Holly Carter Candy, grocery, coffee, dairy, fresh produce, frozen produce, and meat, including a self-service section. Cutting and packaging of picnic meats and cheeses were done in glass rooms visible from the floor.

Employed at the store were 50 men and women, common for large stores like this. Advertisements from the opening week showcase 37-cent pint jars of salad dressing, 17-cent pint bottles of grape juice, and 32-ounce jars of pickles for just a quarter (I had to disregard the mention of a one-pound can of Hershey’s chocolate syrup for just 15 cents to avoid a quick ice cream of my own).

It’s no surprise that this store opened in the years after World War II, a time of significant economic growth where small towns and villages saw the widespread destruction of old corner homes and the rise of commercial chain stores that are more typical of 2025 than of 1900. Unlike the wartime rationing years, the late 1940s saw increased consumer demand, spending, and supply that could absolutely accommodate thousands of food items like the A&P. American families, even in working-class Elmwood, had more disposable income, and stores expanded their offerings to cater to a growing middle-class eager to use their dollars.

Small, specialized stores, like the meat market on New Britain Avenue and Princeton Street or Alfano’s grocery store on New Park Avenue, were replaced steadily by one-stop shops, with supermarkets like the A&P aiming to offer everything a household needed under one roof. Myron Burnham’s grocery store in West Hartford Center was the closest this town had to a supermarket (and it too became a casualty of Finast in the 1950s).

Jane Parker Bakery and Holly Carter Candy were A&P’s effort to create and promote their own in-house brands, normalizing the kind of mass-produced and standardized food products that would later become branded and pre-packaged items. The bakery offered blueberry muffins (you could get almost 20 for a dollar), apple pies, Danish filled rings, gold coconut bar layer cake, and chocolate brownies. Old-time stores in West Hartford often had clerks retrieving goods for customers, but self-service models were becoming more common, allowing shoppers to browse and select their own items. There’s something to be said for the rise of self-service at a time when the majority of the shoppers would have been women.

The A&P, though it was founded in 1859, was expanding quickly in West Hartford and Hartford in the late 1940s. Originally named the Great American Tea Company in New York City as a tea retailer, it was rebranded the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company in 1869, the same year the transcontinental railroad was completed, promoting a more expansive vision for tea distribution. By the late 1880s, they shifted from mail-order to brick-and-mortar stores, opening smaller storefronts that focused on tea, coffee, and spices.

In the 1920s, they expanded beyond tea and coffee into full-line grocery stores, introducing the economy store model that eliminated credit and delivery services to keep prices low. The company also utilized vertical integration, owning its own bakeries (Jane Parker), dairy farms, and food production facilities to compete with local competitors. It was, for all intents and purposes, the Walmart of its day. The introduction of a self-service supermarket model in the mid-1930s allowed it to steadily replace small corner stores with its own layout.

By 1949, boosted by the return of normal life to the United States after World War II, the A&P boasted several locations between West Hartford and Hartford. In Hartford, there were A&P stores at 304 Farmington Ave., 435 Franklin Ave., 740 Maple Ave., 1948 Park St., and 172 Washington St. In West Hartford, the Elmwood location had opened alongside 65 LaSalle Road. In 1949, the store at 674 Farmington Avenue at the corner of Prospect Avenue was opened.

By the early 1950s, the Elmwood store was restyled and included a self-service meat department. In 1958, the store was remodeled yet again with extra space to add new specialty departments, increase the width of shopping aisles, and add new checkouts and grocery shelving.

Unfortunately, what followed would carve away at the A&P until it finally closed. In the 1940s, the federal government had already targeted the company for anti-competitive behavior in a number of antitrust cases, which ultimately forced them to sell off some of its operations. The government viewed their business model as predatory and monopolistic, arguing that it was driving smaller grocery stores out of business and hurting suppliers. By the 1950s, the A&P was effectively operating more like a traditional grocery chain, relying on other suppliers rather than its own infrastructure, which it had been forced to abandon. They simply failed to modernize its stores or expand into new markets at the same pace as competitors, who were rapidly coming onto the scene.

A recession in 1958, followed by creeping inflation into the 1960s, made it more expensive to operate the Elmwood store. Larger operations like Finast on one end and discount stores like the Jupiter Discount Store on the other made it harder to compete, especially when these two were in the same exact plaza a block away from the A&P. By the 1970s, A&P was closing hundreds of stores nationwide. In 1975, the Elmwood location closed.

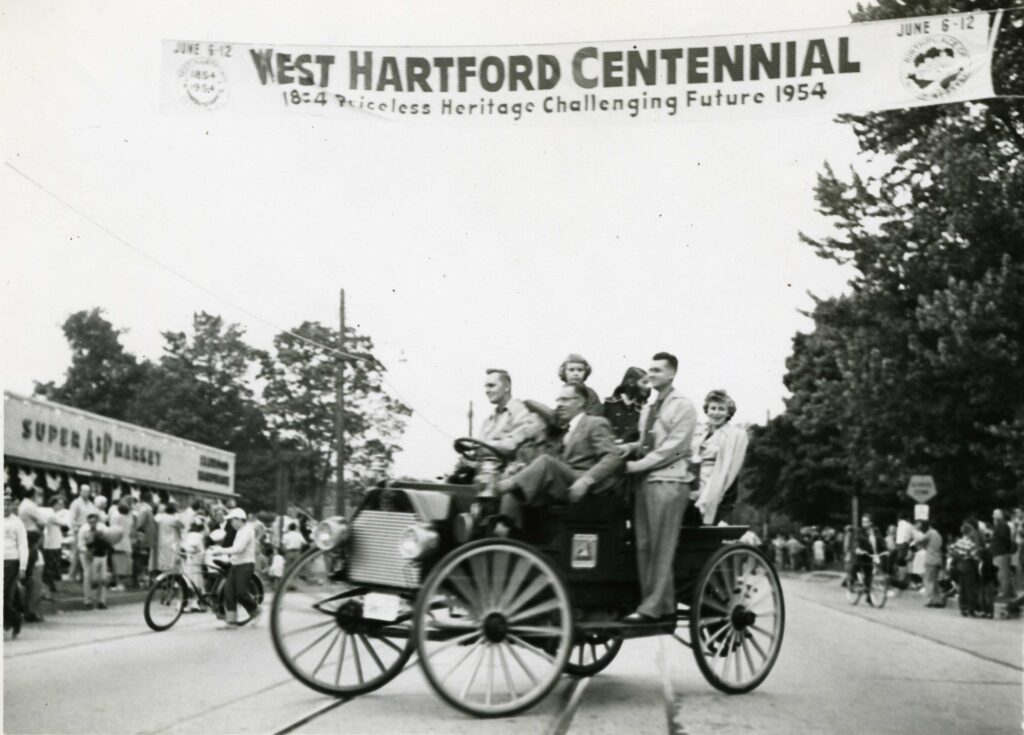

The Centennial parade in June 1954 outside the A&P store on New Britain Avenue. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Located inside the building at the corner though was the Elmwood Hardware Store, which can be seen in the featured photograph. The first mention of it I could find was in 1927 when it was broken into. It was originally located at the corner of New Park Avenue and New Britain Avenue with a number of other stores – a gas station, the Elmwood Drug Store, the West Center Meat Market, and the Elmwood Lunch Room. These stores overwhelmingly catered to the New Departure Company and its factory workers across the street.

In 1913, the New Departure Company hired hundreds of people, nearly half of them women, to do the grinding of ball bearings. New Departure was a leading manufacturer of ball bearings, essential components of bicycles, automobiles, and other industrial machinery.

The early 1900s saw rapid industrial expansion, particularly in precision manufacturing which needed more specialized labor. By 1913, the growing automobile industry made it necessary to expand quickly. This surge predated World War I, meaning it wasn’t just a wartime necessity. Women were traditionally excluded from factory jobs including metalwork or machine operations, but women were increasingly being seen as capable enough (and of course they had the added “benefit” of being paid less than men for the same work). The corner of New Park Avenue became the site of the company lunchroom. This corner was built up over the next 15 years to a two-story building with a variety of stores, often with a food or utilitarian focus.

Having the Elmwood Hardware Store in the same complex just made sense – factory workers were often skilled tradespeople (machinists, mechanists, and builders) who frequented hardware stores for personal projects or side work. Having it next to the company lunchroom meant that workers could stop by before or after shifts (and even during lunch). It was also just very normal for essential services to be clustered at corners like this, including the general store and gas station nearby. It was owned and operated by John Malcom Black, the son of Scottish immigrant John G. Black.

In 1948, when the A&P store building was constructed further west, Black moved the store there, occupying the western side of the building. The store handled hardware, paints, electrical supplies, and plumbing supplies. Ten years later, he retired from the business and the A&P took over his section of the building.

The Black family is almost legendary in Elmwood history (well, maybe just by my standards!). The elder John G. Black moved to Hartford in 1901 at the age of 22, the same year he began working for the Underwood Typewriter Company as a liner. Hartford became a hub for typewriter companies, like Royal or Underwood. In fact, of the 30,000 people in West Hartford who registered to become voters between 1920 and 1941, the second-most frequent occupation for both men and women was at one of the typewriter factories across the city line. Besides insurance companies, which absolutely dominated, typewriter companies were at the center of industrial production in Hartford and West Hartford.

In 1915, the Talcott family sold off land on the east side of South Quaker Lane to a real estate developer, who laid out Burgoyne Street. Black was one of the first lot owners and built the house at 16 Burgoyne Street the following year. This house remained in the family for 103 years and was only sold in the winter before the pandemic. After his death in 1971, his children lived there, including his three daughters.

When I began researching West Hartford history in 2011 at the insistence of my AP U.S. History teacher – Dr. Tracey Wilson – the Black family was one of the first I looked at when deciphering how Elmwood developed.

The eldest daughter Laura was born in 1902 and was a teenager when the family moved to this little village. According to her obituary in 2002, she “became a substitute mother for her brothers and sisters, through their mother’s illness, helping to raise them and care for them in their youth.” Their mother Maud died in 1936, an especially hard time in the depth of the Great Depression. Laura died at the age of 100 in 2002. I remember reading that she still had two sisters – Dorothy and Marianne – who still lived in the same house on Burgoyne Street. I was stunned by the fact that just a few blocks away from me was a family that could remember a time in Elmwood that is long gone today.

When the house on Burgoyne Street was built in 1916, it would be more than a decade for the Elmwood Elementary School to be built. Laura would have remembered vast farmland across from Burgoyne and she would have been in her 20s when Talcott Junior High School was built. The Blacks could see the Charter Oak racetrack from their backyard and the Talcott house from their front yard; it would be another 30 years for the Elm Theater to even be conceptualized.

In 2012, Dorothy Black passed at home at the age of 101. And finally, in 2018, the last sister Marianne passed away at the age of 102. She was predeceased by three brothers and her two sisters, neither of whom had children. There is a lot to be learned from families like this, especially the value of memories. Photographs like this provide us with a window into both the large stores and the lives of the individual people who shaped our town.

CVS is now located at the corner of New Britain Avenue and Newington Road. Google Street view

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.