From the West Hartford Archives: Boulevard and Prospect

Audio By Carbonatix

Mott’s ShopRite at the northwest corner of Boulevard and Prospect Avenue in 1966. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This photograph was taken in 1966 at the Mott’s ShopRite at the northwest corner of Boulevard and Prospect Avenue.

Going back 70 years shows a corner with a single brick house, owned and occupied by the family of Frederick C. Rockwell, notable real estate developer. Throughout 1895, he purchased a significant strip of land in West Hartford and laid out the Boulevard. He created streets that he named after his three daughters – Jessamine, Vera, and Doris [which later became Trout Brook Drive when it was extended north and south]. Born in Missouri, his father had been a California prospector in the 1849 gold rush. Frederick spent much of his early life in St. Louis and Chicago before coming to the Hartford area.

Rockwell is known for his ambitious Boulevard project, but what is less known is that his connection to West Hartford (and why the Boulevard is where it is) was actually through his wife.

Jennie Lockwood married Frederick Rockwell in October 1879 in Hartford. She grew up on the west side of Prospect Avenue in the house that would become the northwest corner of the Boulevard when her future husband would buy up the land and lay it out. Her father, James Lockwood, was a Hartford printer and a partner in the prominent printing firm Case, Lockwood & Brainard in the 1860s.

When he died in 1888, he left the house to Jennie, who had been married for almost a decade. Seven years later, her husband ran a street to the south of the house across the town. The original project subdivided lots in West Hartford Center, particularly at Raymond Road, Meadowbrook Road, and Burr Street.

The Rockwells then embarked on the second subdivided tract in 1910, this time on the east end of town. This development, known as Columbia Heights, opened up 87 lots all along the Boulevard from Prospect Avenue to Whiting Lane, as well as several lots on portions of South Highland Street, Fairview Street, Lockwood Terrace, Lexington Road, and Beverly Road.

Ironically, for a couple that helped develop West Hartford in such a significant way, the Rockwells favored annexing the town to the City of Hartford. A few months after opening the Columbia Heights tract, Frederick Rockwell started gathering people interested in the matter to call for a special town meeting. Those in favor of annexation argued that the town could use the city’s fire and police protection, without any noticeable increase in taxes, while those opposed cited higher tax assessments on their land and a desire to make improvements within the town.

Just like in 1895 when it was first tried, the annexation movement failed. Of course, some of the proponents of annexation dug their heels in and attempted yet again to push the matter in 1912. By that point, however, the Rockwells were no longer residents of West Hartford. They had sold the brick house and a considerable part of the former Lockwood estate in June 1912. They moved to Hartford and only a few years later, they headed to California for good.

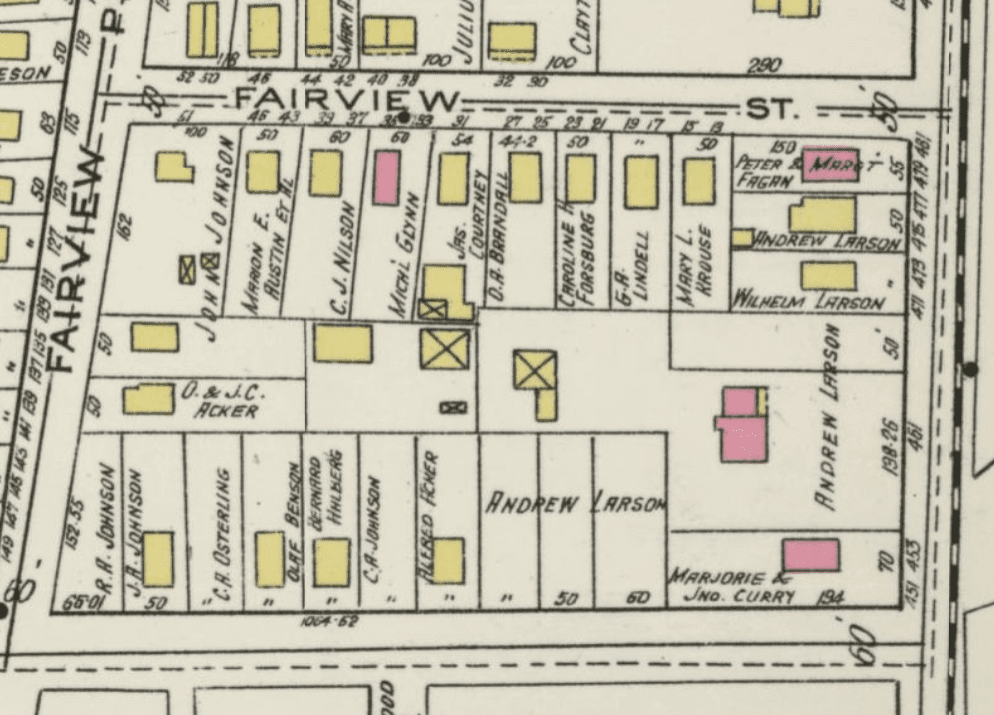

In 1916, the house at the corner was bought by Andrew G. Larson, the town’s building inspector. Larson was a builder who had lived on Richard Street since 1909 and was appointed the building inspector by the selectmen in the spring of 1915 to succeed Frank Stadtmueller.

Through the building surge of the 1910s, the role of the building inspector became increasingly powerful. He was responsible for electrical, furnace, and fire inspections, structural integrity of park and commercial infrastructure, and granting new permits for construction. Larson pushed for the creation of a stringent building code and drafted the first one. At the same time, he built houses and subdivided further lots next to his home on Prospect Avenue and the Boulevard.

When zoning was introduced in the early 1920s, he was given another tool for determining the development of the town. In one situation, he denied a permit for the construction of a market at the corner of Farmington Avenue and Ardmore Road in 1923, prompting a legal case against him to show why. Multiple injunctions would be filed against him in future years anytime an unpopular decision was made, especially when it was subjectively enforcing a town ordinance.

After 25 years as inspector, he died at his summer home in August 1940. The building code he had drafted remained virtually unchanged by the time he died, cementing his legacy as an important yet controversial figure in the development of West Hartford’s real estate.

1917 map of Boulevard, South Highland Street, Prospect Avenue, and Fairview Street. Andrew Larson oversaw the development of neighboring lots.

Between 1920 and 1941, the country with the most immigrants registering to vote in West Hartford was Sweden. Even England, Ireland, and Italy had significantly fewer registrants. The volume of Swedish residents is evident in the names this town has seen – Johnson, Anderson, Carlson, Gustafson, Larson (Andrew being a Swedish immigrant himself), and Nelson. Swedish migrants were pushed from their home country over religious dissent, consistent crop failures, and they were pulled to the U.S. by what they perceived as religious tolerance and better opportunities.

Swedish settlement in West Hartford was a product of how quickly and smoothly West Hartford integrated them. Swedish girls were preferred as domestic housekeepers and maids for wealthy homeowners who often lived on the east side of West Hartford. Their families found a close home along Park Road in the 1890s. Rapid growth of the Boulevard and Park Road area, especially South Highland Street, brought the Swedish population together in a dense neighborhood of two- and three-family houses. This allowed them to develop a better sense of community and establish their own Sunday school and Methodist Church at the corner of Boulevard and Lockwood Terrace.

Following close in number behind were immigrants from Denmark (like Andrew Petersen, founder of A. C. Petersen’s) and then Norway.

By 1960, the northwest corner of Boulevard and Prospect Avenue included an apartment building, two 1920s houses, and the old Lockwood home set back from the street. That would soon change.

The first five months of 1961 were perhaps the most purposely destructive in town history: 46 single-family homes and four two-family homes were demolished to make way for the “East-West Highway,” with several others being moved out of town and to other streets.

As if to follow the pattern, the town approved the construction of a Food Fair store building at the northwest corner, which required the tearing down of the four houses that were on the property. Food Fair, the nation’s sixth largest supermarket chain, had quickly expanded in the Hartford area and looked to West Hartford for a new site. The 22,000 square foot plaza that still stands today went up during 1961 and Food Fair opened its store at 1044 Boulevard on Feb. 14, 1962.

A quick entrance to town was met with a quick exit in March 1963 when Mott’s bought the plaza from Food Fair. Mott’s added an appetizer bar, deli, courtesy counter, salad bar, and bakery. Joseph Mott had looked to buy the corner in the late 1950s for a supermarket, but it was too expensive at the time; now, the ideal spot was theirs. The ShopRite was a commercial landmark for decades but was scaled down in 1987 and ultimately replaced in the early 1990s by a CVS Pharmacy. A number of different stores and practices are there today in the footprint of the old Lockwood house.

Current view of the northwest corner of Boulevard and Prospect. Google Street view

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.