From the West Hartford Archives: Construction of the Pratt & Whitney Factory

Audio By Carbonatix

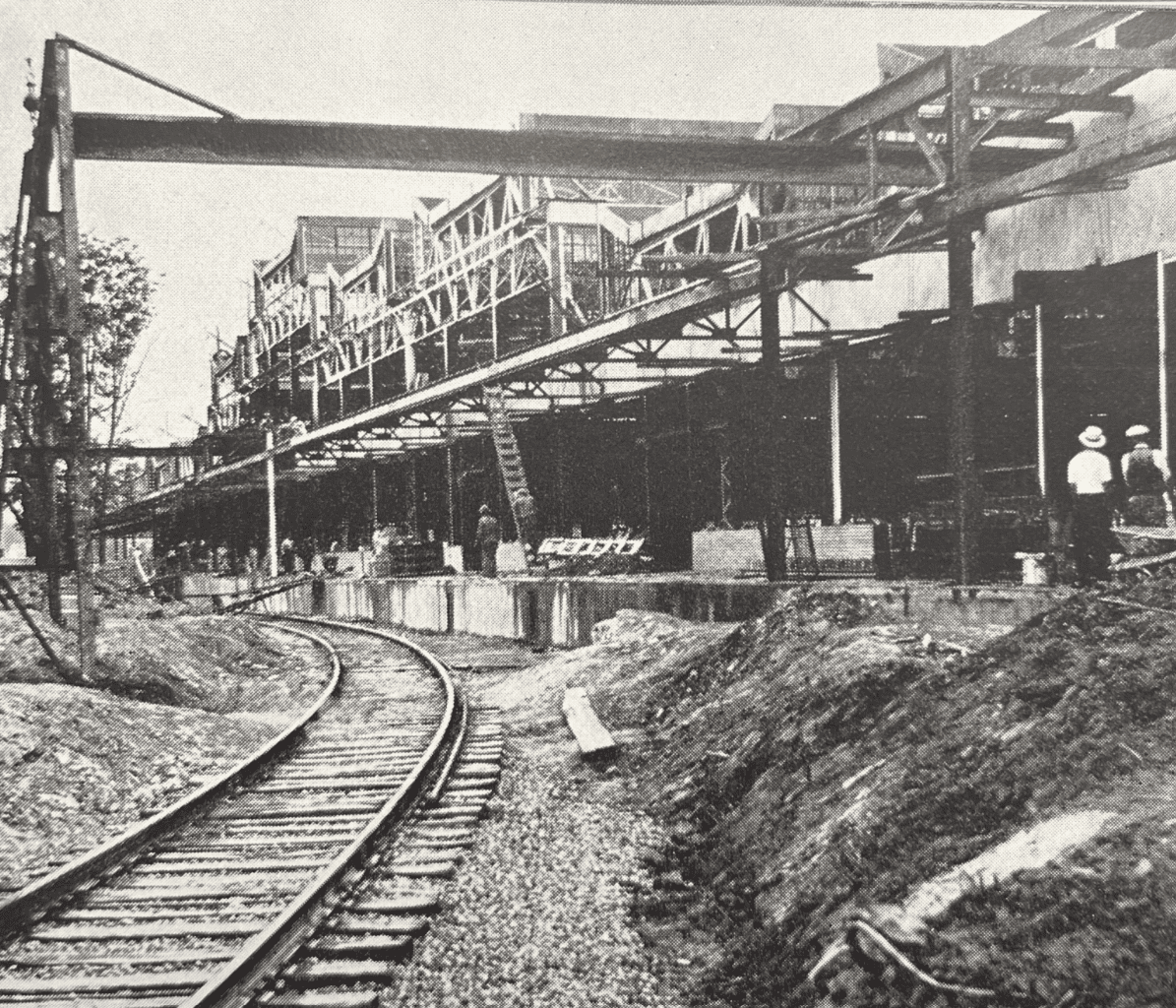

The shipping platform at the rear of the Pratt & Whitney factory in West Hartford. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

In 1940, Pratt & Whitney moved from its old plant in Hartford to a new factory in West Hartford, the current site of Home Depot.

Francis Pratt and Amos Whitney, its founders, teamed up in 1860 to manufacture machine tools in Hartford. The timing could not have been better: the Civil War broke out the following year and created a massive demand for weapons, which opened up a niche for toolmakers.

Traditional craft-based manufacturing was too slow and inconsistent, but speed and scale required accuracy. Their solution to this problem was in better machine tools that relied on better measurement. Interchangeable parts only work if every component is made to the same standard, a luxury we may not think about in the current world. Before the era of industrial progress, measurements varied by workshop, region, or even individual. Once measurements were standardized, parts could be made anywhere and fit together everywhere.

Pratt and Whitney backed research into this new standard system of measurement, which would allow for mechanization and skilled machine design. Over the years, they expanded their factory on Flower Street in Hartford south from the railroad tracks to Capitol Avenue (some of these buildings remain standing at that corner). Pratt & Whitney Tool’s Gage Department manufactured precision gages that verified size and tolerance and ensure parts met exact standards. Their uses spread to railroads, electrical equipment, and automobiles, and they played a direct role in a management theory known as Taylorism: by scientifically studying work, breaking tasks into simple motions, and standardizing processes, factories could significantly increase productivity, efficiency, and profits. Industrial capitalism was expanded greatly at the expense of skilled artisans and working-class employees, who were treated like machines themselves. Labor unions responded with strikes and reforms. Reformers spoke out about the deepening inequalities.

In 1901, the company was purchased by the Niles-Bement-Pond Company, which made Pratt & Whitney one of its divisions. They focused on the automotive industry and then tools and gages for large gun production during World War I.

Once the war was over, the technologies that were developed during it were applied to civilian uses, like metallurgy and production planning. Standards of performance were improved through the 1920s for automobiles, radios, and mechanical refrigerators.

During the early half of the decade, the factory on Capitol Avenue hosted Frederick Rentschler and his team, who were working on building the aviation industry. The 1922 Washington Naval Treaty limited the construction of warships, so the U.S. Navy converted gunships into aircraft carriers and therefore needed aircraft. Rentschler struck a deal with his friend, the president of Niles-Bement-Pond, to create the Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company to develop the next-generation engine, with the support of the Navy. The Wasp engine was designed at the Pratt & Whitney tool campus.

During the Great Depression, the company invested in research and development. They absorbed specialized firms and centralized technologies under a broader trend of corporate concentration. One of the consequences of this consolidation was that it brought Pratt & Whitney to West Hartford by the expansion of its Hartford plant.

In February 1937, Pratt & Whitney purchased the site of the former Charter Oak Park from Chase National Bank for $100,000. I wrote a little over a year ago about the end of Charter Oak Park, the famed horseracing track and grandstand at the corner of Flatbush Avenue and Oakwood Avenue. It had closed in 1931 due to declining revenue and anti-betting laws and fell into disrepair. It became the perfect staging ground for a brand new factory (and just in time for World War II).

The main reason for the move though was to accommodate the modern machine-making process. The old plant in Hartford had production spread vertically across many floors across two dozen buildings. By 1940, machines and parts were larger, heavier, and more complex. Moving heavy castings up and down floors was dangerous and slow. In other words, modern toolmaking was demanding a single, massive horizontal structure for continuous workflow and large machinery. In fact, many current factories follow this sort of flow.

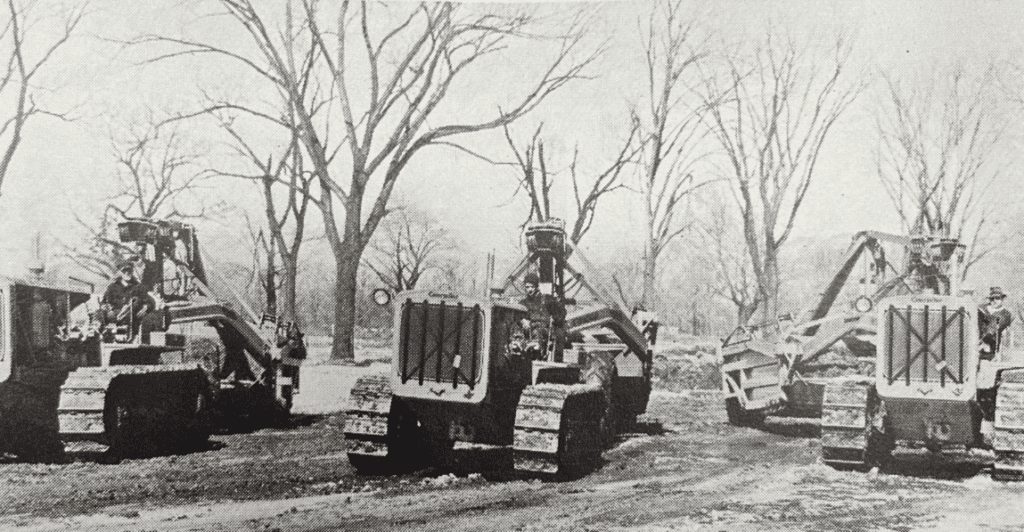

The excavators begin work on the site at the corner of Flatbush Avenue and Oakwood Avenue in March 1939. Courtesy Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

The design of the new factory in West Hartford was done by Albert Kahn, Inc. out of Detroit. They designed hundreds of factories for automobiles (like the Ford River Rouge complex), machine tools, aircraft, and military production. Kahn’s involvement in Pratt & Whitney’s factory is a product of the principles of so-called Fordism: linear movement of parts, minimal wasted motion, and spatial efficiency. Architecture is as much about function as it is about form.

Designing factories around these principles in the first half of the 20th century helped make the U.S. the world leader in mass production. It also reinforced corporate consolidation and widened economic inequality, allowing large firms with modern plants and the capital to sustain them to destroy smaller firms.

Labor responded with the rise of industrial unions, strikes, and demands for collective bargaining and job protections. With the help of Roosevelt’s New Deal, labor won real gains but did not reverse consolidation. It was in this world that Pratt & Whitney removed the last traces of Charter Oak Park and started construction on the new factory in West Hartford.

Work on the new factory started in March 1939 when tractors arrived to remove dirt for the foundations. The general contract for the construction went to the James Stewart Company of New York. Before the development of machinery like this, earthmoving was done entirely by human hands (and shovels, of course). The West Hartford reservoirs decades before were dug out (again and again) by gangs of men, mainly immigrants. Now, during the Great Depression, several of these big “cats” like the ones photographed were used at once on a tight schedule to meet production deadlines.

The timing, although not perfect, is eerie. World War II had not started yet, but Germany had already remilitarized, annexed Austria, and were now occupying Czechoslovakia (that happened the same month excavation started). Many companies, whether they knew it or not, were preemptively mobilizing and expanding their capacity.

Clayton Burt, president of Niles-Bement-Pond, was simply waiting for the winter weather to let up before breaking ground. Once work went forward, work went ahead quite rapidly. In parallel with the excavation, New Park Avenue was shut down to lay railroad track across the road from the main railroad on the east side to the site of the shipping room. Rail was the dominant freight system, with raw materials arriving and finished goods heading back to the main line to be distributed. Even in a highly mechanized system, this kind of work still relied on manual labor. Employees used picks, bars, and hand tools in a labor-intensive back-breaking piece of work.

Workers lay spur track across New Park Avenue from the railroad on the east side to the future Pratt & Whitney site. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

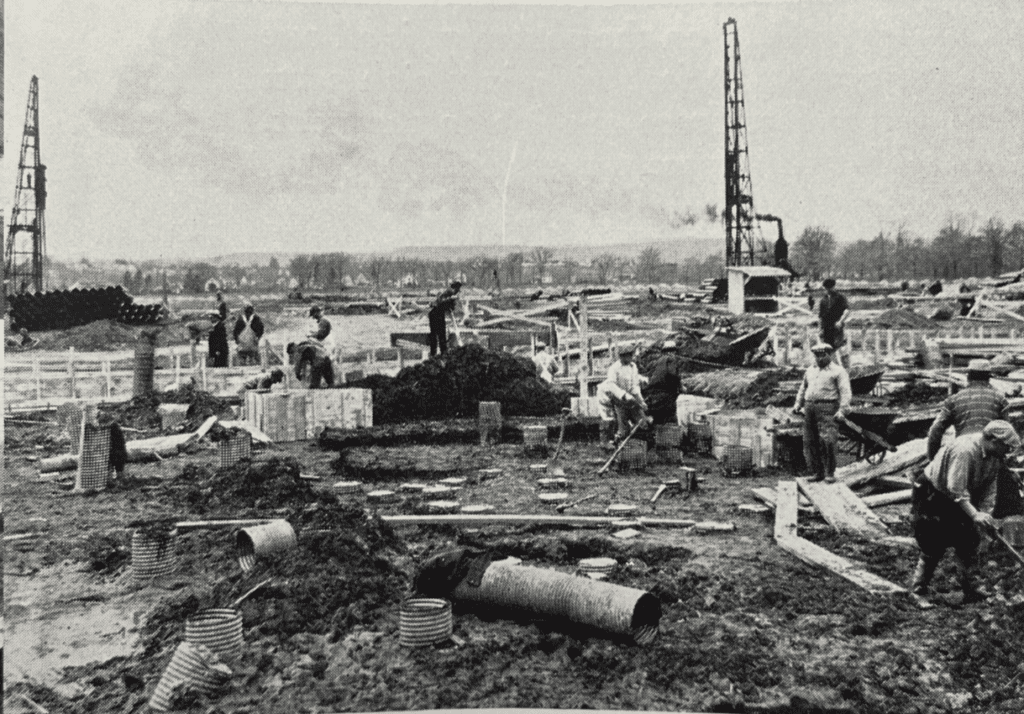

Once excavation work was done and the rail line was installed, the foundation was ready to be established. The entire factory would be supported by 1,628 timber columns (called piles), each nearly 100 feet long. The timber came from 70-year-old trees originating from Oregon and shipped across the rail spur to the plant. This type of foundation was designed for extreme loads and vibration and therefore these piles had to be driven deep into the ground, where they would rest against dense soil and bedrock.

You can’t just dig a hundred foot hole and drop a pile into it though; it had to be forced into the ground by a steam pile driver. A boiler on site attached to the pile driver generated high-pressure steam, which lifted the steel hammer up a frame. This would then drop onto the top of the pile hundreds of times until it was forced deeper into the ground. The piling work was done by the Raymond Concrete Pile Company of New York (it went bankrupt after 90 years of business in 1989 and only its Middle East operations in Bahrain remain).

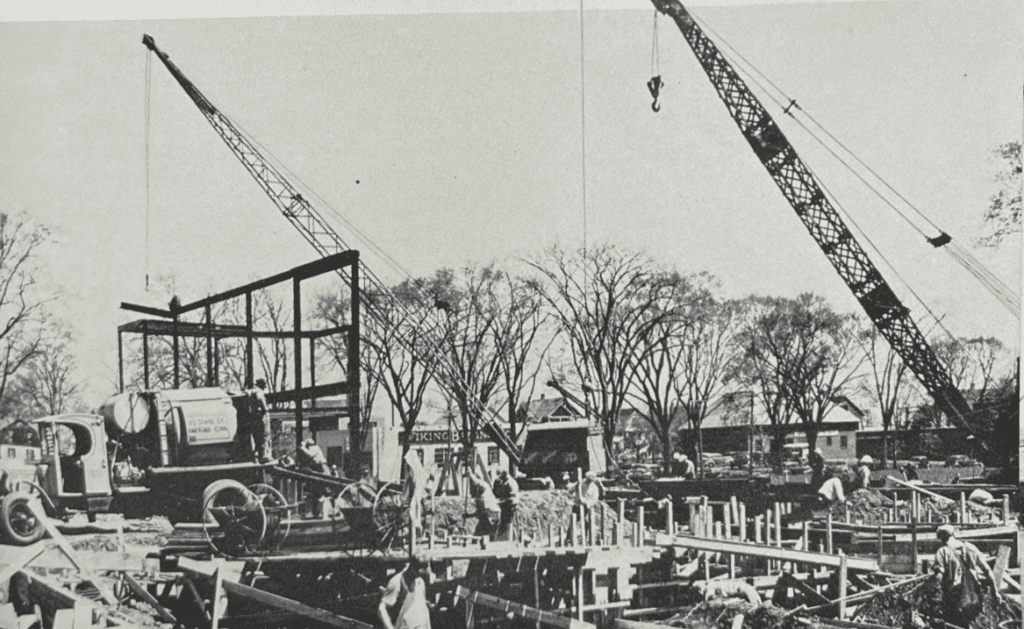

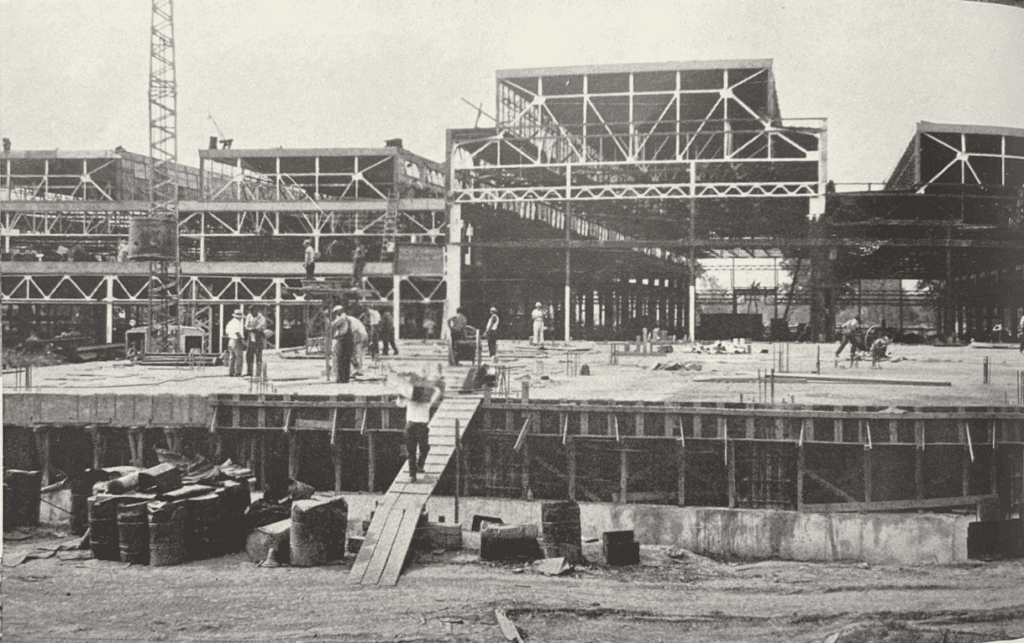

After the piles were driven into the ground, workers built wooden foundation molds (called forms) around the pile tops, which would shape the concrete to be poured. Concrete capped these piles and turned many into one stable system allowed to settle. Once the concrete cured, the wooden molds were removed and the construction of the steel frame could begin.

The first foundation was for the pattern shop of Pratt & Whitney, the place where patterns were made for casting metal parts. The pattern was the master copy from which all metal parts originated; their work before had been based around the castings for lathes, milling machines, grinders, and precision measuring equipment. They had to be more accurate than the parts they produced and therefore the pattern shop sits at the very start of the chain. In total, 57 million pounds of concrete were used in the construction of the plant.

The steel frames were manufactured by the Bethlehem Steel Company of New York, one of the largest steel producers in the world. By the late 1930s, they were central to skyscraper construction (like the Empire State Building), railroads, bridges, and ships. They supplied naval and military contracts even before World War II.

Once the steel went up, it was followed by glass and brick in quick succession. The shop was finished and occupied on July 1, 1939. It took a few more months to complete building of the administration building, the powerhouse, and the shipping platform at the rear of the complex, but moving from the Hartford plant turned out to be just as demanding, taking two months. 950 machines were moved from the Machinery Department and 1,350 from the Small Tool and Gage Departments, weighing 23,000 tons in total.

Over a year of development, the new plant required the work of 2,000 men full time and doubtless hundreds of women who worked as clerks for the companies that manufactured and shipped the steel, concrete, and brick. 110,000 panes of glass over 5 acres allowed for near-perfect lighting conditions; General Electric supplied the lighting. Factories using GE lighting were deeply embedded in New Deal and later wartime infrastructure.

Workers constructing the foundation forms that molded the concrete that capped the timber piles of the foundation; one of the pile drivers is seen in the background. This is likely looking west to South Quaker Lane. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Workers backfill soil and leveling the ground after the concrete pour during the foundation of the pattern shop. Oakwood Avenue (and the Viking Baking Company) can be seen in the background right. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

In 1940, hundreds of West Hartford residents worked for Pratt & Whitney at this plant. Some were old-time employees, like William J. Walch. Born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Walch came to Connecticut in the 1895 and worked at Pratt & Whitney (first at the Hartford location and then in West Hartford) for over 40 years as a toolmaker. His home was at 185 South Highland Street.

Edward Cady also had over 40 years of experience at the company. He was employed as a foreman when the company moved operations. Originally living in Hartford, he moved to West Hartford in 1937 and took residence at 57 Oakwood Avenue, at the other end of the road from where the factory would be built. Maybe his move was prompted by Pratt & Whitney buying up the old Charter Oak Park.

May Cutler, wife of Kenneth A. Woodford, worked at Pratt & Whitney for 21 years when the plant was built in 1939. Born in Missouri, she moved to Hartford in 1918 to work there as a secretary. She moved to West Hartford before construction and lived at 152 Whiting Lane until her death in 1951. The records are filled with West Hartford residents who worked there as patternmakers, gauge makers, secretaries and clerks, engineers, designers, and managers in 1940.

Steel work begins on the new factory in the spring of 1939. Note the Viking Baking Company building in the center background! It opened at Oakwood Avenue in this location less than six months before construction. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Construction of the main building is almost done and the first floor of the administrative building (foreground) on Flatbush Avenue is poured.. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Less than two years later, the United States entered World War II and those same employees (and more) turbocharged their work in support of the homeland. 4,600 workers congregated in the main building a week after the attack on Pearl Harbor and pledged to break records in production to “smash the enemy on the battlefield.” This defense production rally was led by Governor Hurley, a Captain of the U.S. Navy, the deputy chief of the Hartford Ordnance District, and the union president.

A month later, U.S. Army leadership visited major industrial plants in the area, including Colt Firearms and Pratt & Whitney in West Hartford. The workers were framed as soldiers and output speed was considered decisive to victory over the Axis. “If you fail us, we become an Army without arms,” said Lt. Col. A. Robert Ginsburgh. “If we fail you, you become workers in chains.”

Pratt & Whitney was responsible for making the precision machine tools that enabled Colt to make firearms, aircraft plants to make engines, shipyards to make machine components, and arsenal factories to scale output. West Hartford workers became soldiers and Oakwood Avenue become their battlefield. The plant worked almost continually since then until the end of the war.

When news of the Japanese surrender reached Hartford, second shift workers had just punched in. The whistle sounded and all war plants turned to a day of rest.

The construction of the Pratt & Whitney plant in 1939 was emblematic of American industry on the eve of World War II and the operations that took place inside its walls made possible the postwar industrial dominance that followed. These construction photographs truly embody the spirit of a country on the precipice of the economic miracle.

The completed plant in 1940, looking from the corner of Oakwood Avenue and Flatbush Avenue. The administration building is at the right. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Hello Jeff:

Keep up your outstanding work. I am very familiar with Pratt & Whitney. You educated me and other readers with detailed information.

Sincerely,

Jimmy Johnson, Conard alum.

http://www.JamesAJohnsonEsq.com