Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This is quite an early view of the front entrance to 240 South Main Street at the southeast corner of Crestwood Road, looking south across the hill that still exists at the edge of the property.

It was built in 1915 by the local construction firm McIntyre & Ahern for William S. Brockway from the plans of Smith & Bassette. When he purchased the property that year (about 30 acres), it had an unobstructed view of Hartford and the surrounding area. Interestingly, he had made the move with his family from their old house on the top of a much wealthier Prospect Hill to the farmland of South Main Street at a time when most of the wealthy were sticking to the avenue and in the West End of Hartford. In fact, the Brockways had already built on the hill (999 Prospect Avenue), but seven years was all they needed and 240 South Main Street became the new frontier.

Brockway worked in the real estate office of his father Edward Payson Brockway, who in his early years had been a pioneer and settler in Wisconsin in the 1840s. It seems that Edward was quite the entrepreneur there – he manufactured flour and lumber, then opened one of the first banking offices in the state, and then conducted a stock farm until he came to West Hartford in 1908 to live with his son on Prospect Avenue.

The land that Brockway bought on South Main Street extended from what would become Crestwood Road (at that time, it was simply the northern boundary of the property) south to what would become Rockledge Drive. This was formerly the farm of John Millard, a longtime West Hartford resident whose family had deep ties to the beginnings of the town. His brother Theron lost his life in the American Civil War. His sister Electa married Benedict Hamilton, who laid out Hamilton Avenue between Farmington Avenue and Fern Street. His niece Ellen married William Hall, the first principal of the high school in town and longtime superintendent of schools. Another niece Elizabeth married Henry Day, a prolific builder and the brother of Louise Day Duffy.

These connections among the townspeople were quite common and reflected just how much impact individual families could have on the trajectory of the town’s development, just by a single marriage. Millard himself was born in the 1830s and represented the town in the State Legislature in 1880. His market business was run on the farm for many years until his health declined. In 1913, he sold the property and moved in with his daughter to live out his last years.

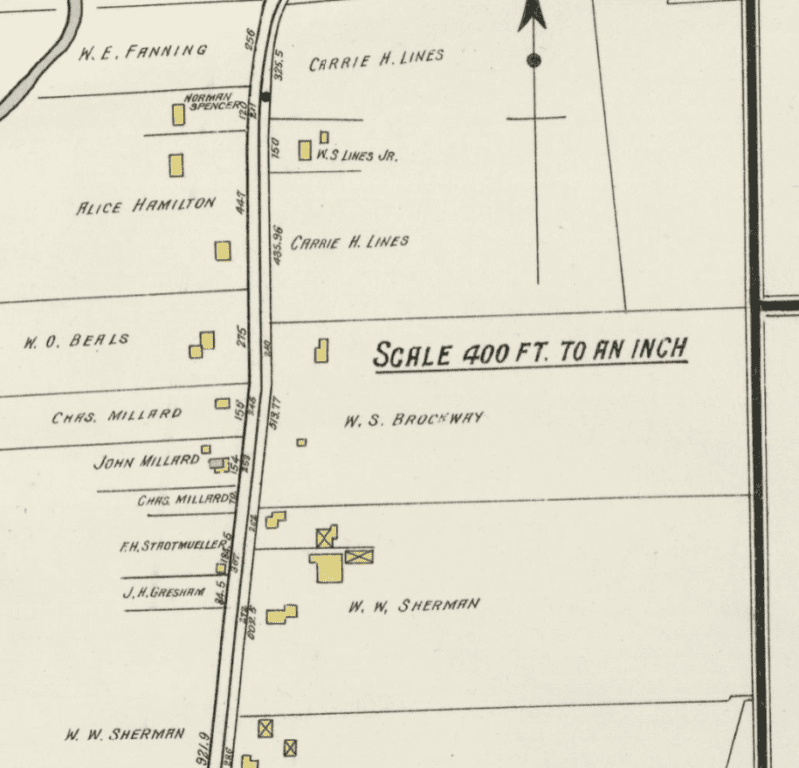

Map of the area on South Main Street in 1917, including the Brockway house at 240 South Main Street

With all the buildup, one would think the Brockways lived at 240 South Main Street for a generation or two, but in fact they moved in during the spring of 1916 after it was built and sold it just four years later to Irving Ingraham and moved to Massachusetts. Ingraham was president of the Hartford Tube Products Company, which had just been founded less than six months prior. The company built a factory in the industrial section of Elmwood in the rear of Newington Road along the railroad and manufactured iron and steel pipe and copper tube coils for refrigerating and heating. The company went bankrupt just five years after it was established, but the building remained and is still off of Brook Street.

Soon after, the South Main Street house was purchased by Stanley P. Rockwell and his wife Ruth Gowdy. Rockwell owned his own metallurgical business and lived there through the 1930s. It was, however, during their occupation that the area changed drastically.

The land to the south of 240 South Main Street all the way to the path that cuts through to Webster Hill School was the farm of John D. Browne, president of the Connecticut Fire Insurance Company. He had purchased 85 acres of land from the old Coffing estate in 1901 and managed a hay farm there while he lived in the city. He consolidated the surrounding land from other families by 1908, bringing the land total to 110 acres. This farm for a period of time became a sandbox for testing new trucks that could perform better than horses.

Browne himself went out to the farm and spent five days away from insurance work to get his hands dirty again that summer (the Hartford Courant absolutely could not resist the moniker of “Farmer Browne” and neither would I). Across the street were the ruins of the old West Hartford rock quarry.

When roads began to be paved in the 1890s with crushed stone, the town operated a stone crushing plant in the area that is now Rockledge Golf Course. Thousands of pounds of dynamite were shipped in and used by a dozen or so Italian laborers over the course of ten years to blast rock out of the ledge, transforming the landscape. In the summer of 1900, the whole plant burned down in a tremendous fire that started in the engine room. It completely shut down operations and the town moved it elsewhere, abandoning it for more than a decade. They were therefore happy to sell the land to John Browne in 1912.

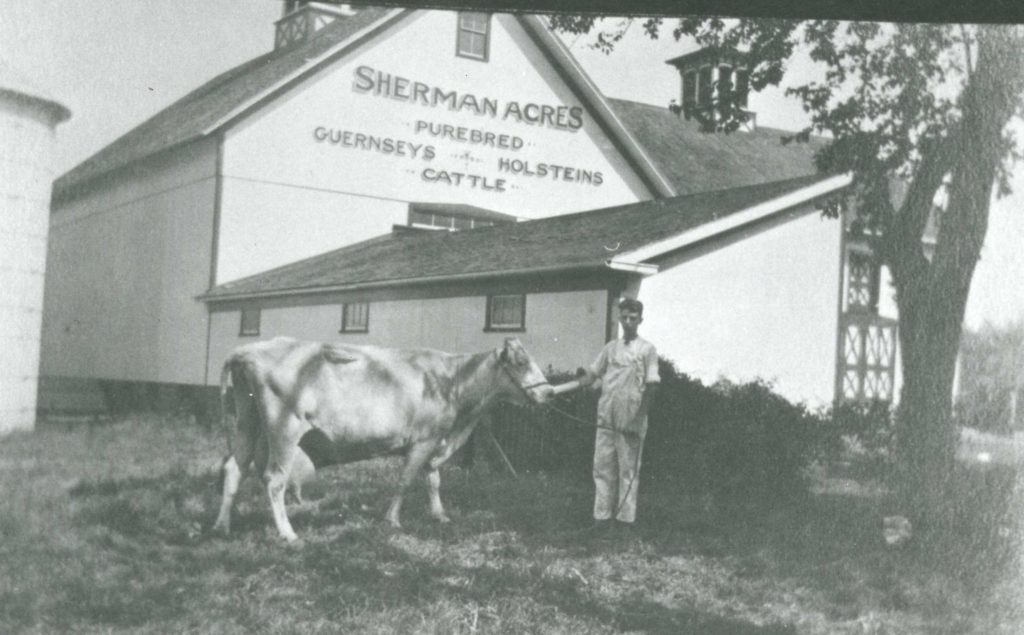

Browne died soon after, however, and within six months in 1913, his entire estate was bought by Wilton “Mike” Sherman. Now in possession of land on both sides of the road, as well as two houses, Sherman conducted a dairy farm known as Sherman Acres. Around World War I, Sherman was introduced to a group of businessmen with the idea of a golf course on the west side of South Main Street, but he was advised against it. However, he stuck with the idea and about a decade later, he organized the Rockledge Country Club with a golf course that was laid out in 1924. It was expanded soon after and purchased by the town more than three decades later.

Sherman Acres farm on South Main Street. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

The land to the north, from Crestwood Road to 202 South Main Street, where the road curves to the right, was owned for more than two decades by Carrie Lines. She, along with her son, had an immense number of real estate holdings in town, including 30 acres at the northeast corner of Farmington Avenue and Mountain Road; several blocks radiating from North Quaker Lane and Fern Street; and a chunk of land on Farmington Ave between Arlington Road and Stanley Street. In the spring of 1927, she was approached by James F. Ryan, a real estate developer, to sell 17 acres of the land she owned on South Main Street.

Directly across from the Noah Webster House and a short distance from the new Rockledge Country Club property, the land was definitely valuable, but it was even more valuable if it had streets and houses for prospective new buyers. Lines agreed and Ryan bought the land, laying out Webster Hill Boulevard as the first street in this tract known as Webster Heights. He also laid out Crestwood Road, which was known originally as Westview Avenue. The newspaper reported that on Webster Hill, one could actually see Fairfield Avenue in Hartford.

A few months later, Ryan bought the Sherman Acres farm on the east side of South Main Street from Mike Sherman and called it the Webster Heights Addition, creating Rockledge Drive in honor of the country club across the street. Therefore, in the summer of 1927, James F. Ryan had carved out streets all around the house that Stanley P. Rockwell lived in. Of course, that meant that Rockwell had to get in on the fun. He laid out Rumford Street right through the middle of his land and subdivided the land along the south side of Crestwood Road and Rumford for new houses in a tract he called “Rockwell Terrace.” The grand plan was actually to extend the roads all the way across Trout Brook to connect with South Quaker Lane, but that never went forward.

Further south, Ledgewood Road and Bentwood Road were laid out much later and included racially restrictive covenants that will be the subject of a future article. These new developments in just the late 1920s were the product of newfound suburbia, but it also essentially set the foundation for the massive population growth in the 1940s and 1950s that would prompt the construction of Webster Hill School right in the middle. It also meant that 240 South Main Street, pictured in this article before all of these massive changes, was one of the few constants in the neighborhood.

Some owners sold the land for new streets and some, like Rockwell, capitalized on the rush themselves. The streets grew in the area like vines – to one person, the growth that sacrificed all of that farmland may have felt like impending doom; to another, it was the tasty fruit of seeds planted generations before. It just depends on who you ask.

Current view of 240 South Main Street. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

So informative, once again. It seems that there were a number of shrewd, lady, landowners in early West Hartford, interesting.

An additional question: What was the status of the Noah Webster house during this time? Was it lived in? Was it a ‘landmark’? The emerging street names clearly indicate an awareness of it’s heritage. I can’t imagine it sat in mothballs for over a century. What is the history of its restoration?