From the West Hartford Archives: Elmwood Plaza

Audio By Carbonatix

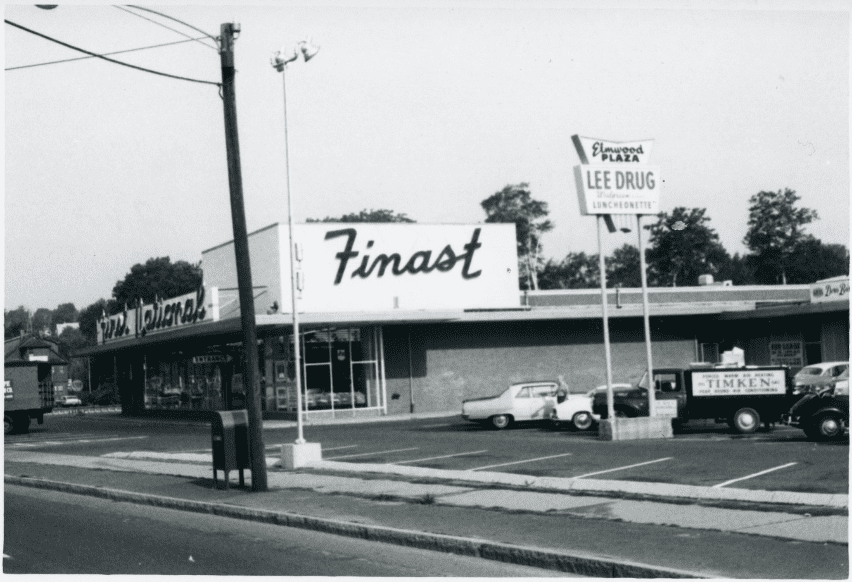

Elmwood Plaza, 1966. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

Historical photographs of any plaza in West Hartford seem to capture a selection of stores that either just appeared or were about to leave. Turnover in commercial establishments is common, making it especially important to take these snapshots almost every year just to keep up. This photograph shows the northwest corner of New Britain Avenue and South Quaker Lane – the Elmwood Plaza (or Epstein Plaza, depending on who you ask) – in 1966 to document a zoning violation.

As a recap of a previous article written almost a year and a half ago of an earlier era, this corner was the land and colonial house of the Talcott family. Samuel Talcott acquired the family home and surrounding land in 1789, taking over the woolen mill at Trout Brook back from the corner. His son Henry Talcott, who was born in this house in 1815, was instrumental in advancing the town’s education system, advocating for modern schools in the 1840s, playing a key role in establishing the first high school in 1872, and serving as one of the town’s first selectmen after its independence from Hartford in 1854. His dedication to education continued as he chaired the town school committee and taught adult Bible classes until his death in 1888.

Henry’s children, particularly his son Francis and daughters Eliza, Emeline, Elizabeth, and Sarah, continued to influence the development of Elmwood. Sarah Whiting Talcott, a Vassar College graduate and accomplished artist, lived in the family home until her death in 1936, using part of it as an art studio and antique shop. Her sisters played key roles in founding, with the help of a neighbor Julia Faxon, the Elmwood Literary Society, which later evolved into the branch public library (now the Faxon Library). Their brother Francis operated a poultry farm across from the family home, with his 1865 house still standing at the corner of Burgoyne Street.

It was through his family that the local real estate developer acquired the land and laid out Burgoyne Street (more land north was also sold during this time for the layout of streets just south of Talcott Road to a second developer). It was also through the family (a cousin, James Talcott) that the Town of West Hartford acquired land for the new junior high school in the early 1920s to handle an incredible growth in the population.

After World War II, the U.S. economy experienced a period of rapid expansion, which led to increased consumer spending, suburban growth, and a demand for modern retail spaces. Shopping centers became a new trend, offering convenience to suburban residents who relied more on automobiles and outgrew the old corner markets of the day. Shopping patterns changed – small, locally owned stores were removed for larger, centralized shopping plazas with parking lots, especially if they offered multiple stores in one location.

The postwar period was also a time when older buildings were frequently demolished to make way for modern infrastructure. I contend without any hard evidence but just observation that the 1950s was the most destructive decade for West Hartford, tearing down dozens of homes, stores, and farm buildings to usher in an era of “progress.” Historical preservation was not yet a widespread movement and colonial homes in West Hartford were removed for new developments without significant public resistance. But sometimes there was resistance and developer support for preservation and it paved the way for exceptions that still stand today.

In the fall of 1952, work on Elmwood’s new shopping center at this corner went forward. At the east side of the corner was the Talcott house; on the west side was Pasquale Torizzo’s nursery across from Princeton Street. Once Torizzo sold his place, he started his second nursery up the hill off Knollwood as a result, where most people remember it. Real estate developer Irving Stich of the Realty Development Corporation bought up the property that fall. Stich, a prominent member of the Hartford Jewish Federation, was instrumental in many of the residential developments in this area of Elmwood through the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1950, his construction company started 60 houses on Manchester Circle behind Beachland Park. In the late 1950s, Stich was approached by the town council to sell a lot that extended into the rear of Beachland Park for a walkway for school children who were technically trespassing every time they took this path. There was a bit of opposition that this sale was not necessary, but eventually Stich decided to donate the land for the right of way and help cover the expenses for a plaque along the walkway dedicated to Rabbi Abraham Feldman. Stich’s real estate company helped fill in the gaps between the parks, schools, and WWII-era housing along Mayflower Street.

The Elmwood shopping center was designed by Kane and Fairchild and was set to include a supermarket Mott’s (who originally signed the lease), a large drug store, and about 10 smaller shops, with off-street parking space for 300 cars. Torizzo’s nursery fell, but removing the Talcott house would be harder, especially for the occupant at the time, Harold DeGroff, an interior decorator.

Once Stich bought it, he offered the home free of charge to anybody who was willing to remove it from the lot. DeGroff appealed to nascent historical societies, who “turned a deaf ear.” The state historical society refused to bother with the effort since it wasn’t considered architecturally rare or unique enough to save. DeGroff took a personal interest in preserving the interior, but the exterior was just not special enough. He thought about having it moved next to the Talcott Junior High School to turn it into a clubhouse for the local historical society, but that didn’t pan out either. He set a target of $25,000 as an estimate to buy new land, lay a foundation, and move the house, and within a few weeks, he had raised some money from volunteers. Construction was delayed for two years and in that time, DeGroff continued working to set up the move.

In the spring of 1954, he went to the Zoning Board of Appeals to ask for approval to move the house to 1168 New Britain Avenue, nearly across from Somerset Street on the north side. The petition was granted. With a week left before construction was set to begin, the house was propped up onto rollers and moved west to 1168 New Britain Avenue, where it still stands. The shopping center was completed in 1957.

If any two-year defines Elmwood’s change, it is absolutely 1954-1955. The difference before and after is stark. Stores and businesses opened along the entire stretch of New Britain Avenue from Hollywood Avenue to South Quaker Lane. A new Hartford Federal Savings & Loan Association building had been built at Newington Road. The massive Puritan Furniture factory and showroom went up on the former Lord house grounds and South Street was seeing more and more commercial buildings constructed around the houses. The Elmwood Elementary School had just been knocked down and replaced by the brand new Faxon Library.

The block between Newington Road and Grove Street was expanded and parking provided for the Fernwood, Deluxe Package Store, and Mayfair 5 & 10. West of Elmwood Center was the brand new plaza under construction at the northwest corner, which included a photo studio, barber shop, paint store, laundromat, children’s clothing store, florist shop, aquarium, jewelry store, drug store, and supermarket. Several building blocks were put up on the south side from Grove Street to Colonial Street.

At the heart of this growth was the Elmwood Business Association, formed in 1951 by a handful of businessmen meeting in the basement of a store. The EBA was active in holiday events, sponsored sports teams, and promoted a summertime retail event known as Elmwood Days, when dozens of stores collaborated to slash prices on goods as much as 50%.

West end of the Elmwood Plaza in 1966. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

The Elmwood Plaza was completed in 1957 and six stores, including the First National supermarket, opened on May 1 with an official dedication. The other stores included Modern Hardware & Supply Company, Dressler Men’s Wear, Peter Bobjohn music store, Lee Drug, and Elmwood Pastry Shop, which had been in business for almost 10 years in the Elm Theater plaza.

Peter Bobjohn sold Hi-Fi accessories, phonograph records, and Hallmark greeting cards. Lee Drug occupied 3,000 square feet of shopping space and advertised “self-service merchandising counters” with a cosmetic bar, luncheonette, and prescription counter. At the east end of the plaza was the impending opening of a S. S. Kresge store, which featured electrical appliances, lawn furniture, and garden equipment. During Elmwood Days promotions, sleeveless blouses were two for a dollar and shorts for 53 cents.

In the early 1960s, the Elmwood Business Association petitioned the zoning board for approval to run a festival with amusement rides in the Kresge’s parking lot, but it was denied. In 1961, an addition to the east of the Elmwood plaza was built and occupied by the Elmwood office of Mechanics Savings Bank, next to Kresge’s. It operated at this location, now Zaytoon Mediterranean, until the early 2000s. Mechanics Savings Bank was also blamed for promoting adjustable-rate home loans in the 1990s that led to a number of foreclosures in the Spice Glen housing tract just north of Talcott Road. Adjustable-rate mortgages, low down payments, and allegedly loose lending standards, concentrated into the Spice Glen debacle in 2000, all laid the foundation for the housing bubble that burst in 2007.

In 1961, many underperforming Kresge’s locations were rebranded as Jupiter Discount Stores, a division of the company that focused on “no-frills” shopping and budget-conscious consumers. Soon after, S. S. Kresge opened their first Kmart store in the United States. Both stores were attempts to penetrate the discount retail market, which had become increasingly important.

By the late 1950s, higher wages and inflation increased the cost of living and a recession pushed many families to look for ways to save money. Families through the early 1960s were drawn to discount stores that embraced a “self-service” shopping model inspired by the 1950s grocery stores. Improvements in supply chain management, like trucking and warehouse logistics, allowed large stores to stock items more efficiently and sell them for less.

These stores were designed to offer a variety of goods under one roof, often in bulk and at reduced prices. It’s part of the reason that many of our discount retailers started in the early 1960s – Kmart, Target, and Walmart all opened their first stores in 1962! The Kmart brand won out (until its last mainland store in 2024), but in 1966, Elmwood’s Kresge’s took on the Jupiter Discount Store name. That probably explains why it went out of business in a year – at the end of 1967, it closed down and was auctioned off. In 1968, the Epstein Brothers used the former Jupiter space as their showroom (and it is still there today).

This zoning photograph tells a lot. It is a representation of the maturing economy after the incredible growth West Hartford and Elmwood witnessed during the late 1940s and 1950s after World War II, when discount stores began to creep onto the national scene. The relocation of the Talcott house raises a recurring theme: the tug-of-war between historical preservation and modernization (and the people who push both forward). It also can provide us a lesson for how local stories can provide a lens to national trends and their impact on everyday life.

These photographs, even to capture zoning violations, remind us that places and their histories can disappear quickly without efforts to document them. Every building, store, and street corner carries with it the forces that molded it.

Elmwood Plaza, January 2025. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

The Hungry Crab is now in the space that was formerly Finest at 1144 New Britain Ave. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.