From the West Hartford Archives: Local YMCA Rooms

Audio By Carbonatix

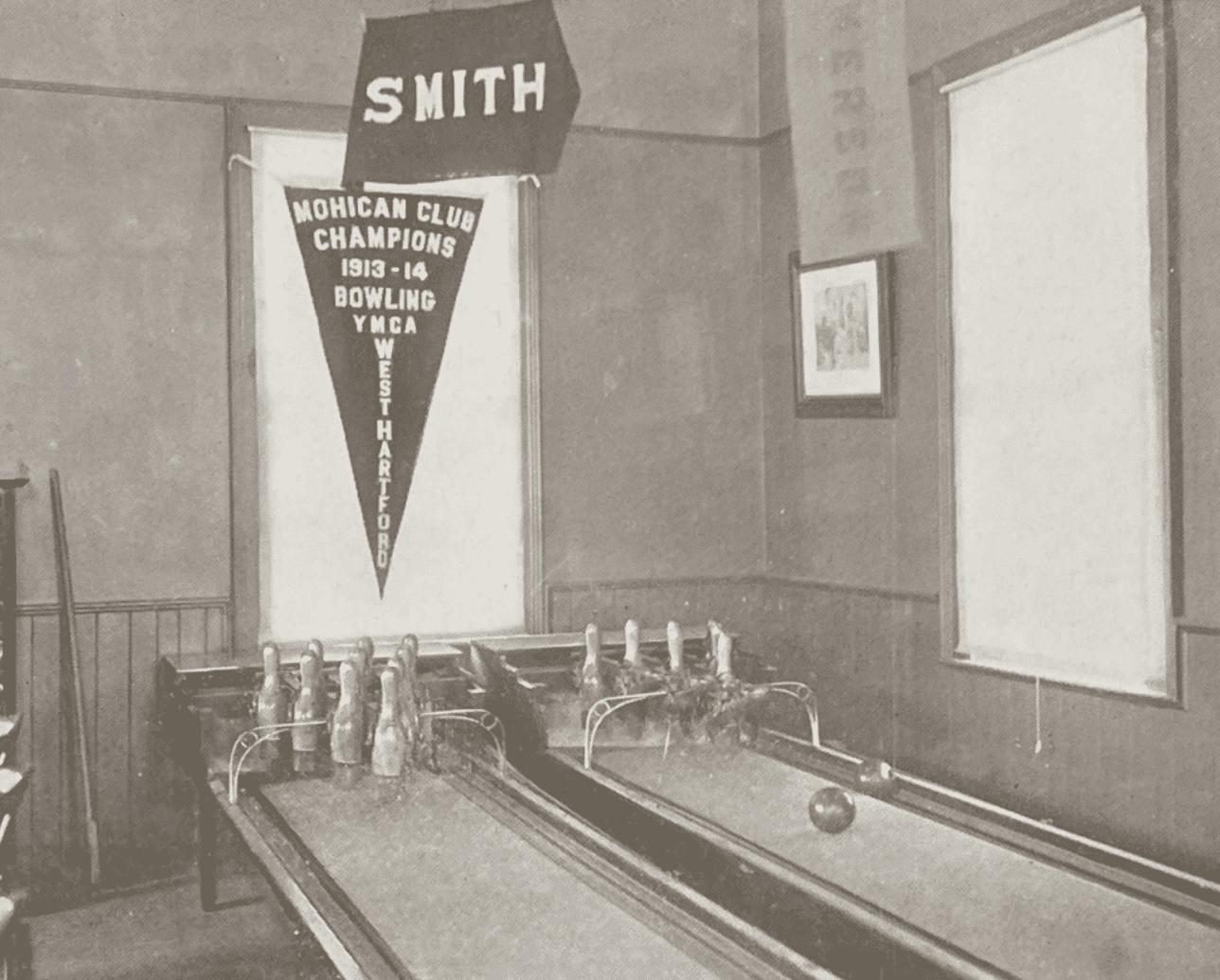

The Mohicans were winners of the first bowling tournament organized by the West Hartford YMCA. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The West Hartford branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was formed in October 1912 to arrange a place for young men to meet and spend the evenings indoors during the winter. Americans were deeply concerned with the social consequences of rapid industrialization and the pull away from traditional church work. Organizations like the YMCA had been the promoters of Bible study in the late 19th century, but by the 1900s, their methodology evolved beyond the church rooms.

Across the country, they emphasized the idea of Muscular Christianity (that physical strength and moral character were linked) and structured recreation to counter the urban temptations of saloons and gambling halls. The bars of Hartford and the betting rings of Charter Oak Park inside West Hartford provided easy evidence that young men had drifted away from the church mission.

In December 1911, the Hartford Courant noted that a nationally influential Protestant campaign, called the Men and Religion Forward Movement, was prompting the creation of branches of the YMCA across the state. The anxiety that churches were losing people, that life was pulling them away from religion, and that Christianity needed to be active to survive was not new.

West Hartford’s history is full of these stories, even in the late 1700s, but the solutions tended to focus on the population as a whole. Early West Hartford, like other towns in New England, saw religious revivals, emotional surges of energy that could waterfall through the townspeople and counter the apathy. For example, Julia Mills wrote about her experiences during a revival in West Hartford in 1808. As the daughter of Jedediah Mills, who lived at the corner of New Britain Avenue and South Main Street, she re-committed to the church after she almost died during an epidemic while she was away from home visiting friends. Her autobiography writes of anxiety, dread, and terror during her process being re-acquainted with Christianity. She was sleepless, agitated, and unable to speak over several weeks and even months, oscillating between hope and despair. Religious revivals were exceptionally unnerving, even if they were exciting. Women’s spirituality in the 1800s was deeply relational and her conversion was shaped by peer pressure and family discourse. She expresses a constant belief that she is unworthy and deserves eternal damnation, even after she’s re-committed to the cause. She died less than a decade later at the age of 37. She went to the grave convinced that her painful illness that took her was proof that she deserved destruction. Religious solutions for straying from the church were predominantly emotional and abstract.

In the middle of the century, these anxieties reflected in tensions with other denominations and over moral issues, like slavery. By the 1870s and 1880s, they manifested in increased meetings over Sunday School attendance. As industrialization emerged and cities like Hartford grew, the churches coalesced around the idea that modern life was specifically pulling men away from religion, but Protestantism specifically framed social problems as personal moral failures. Men drifting from church were weak and susceptible to temptation.

By the early 1900s, reformers were convinced that men could not be fixed without fixing their environments. Modern systems, as they believed, produced sinners and therefore institutions like the YMCA became central to reel in the men playing in the world of business and professional culture. Local committees of the Men and Religion Forward Movement were formed in both the Congregational Church and Baptist Church in West Hartford to address the problem of untethered young men and they settled on the idea that a YMCA branch could be formed here. Over the winter of 1911-12, a canvas of the town was taken and it was determined that there was a number of “young men among us who are not vitally related to our churches, and who apparently [are] not greatly influenced by our Christian activities as now organized.” In the fall of 1912, the new branch of the YMCA came together and leased the brick building on North Main Street, just north of the Center, that had served as the town’s high school and then as a Masonic hall.

The YMCA rooms, formerly the Center School on North Main Street, in 1914. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Instead of revival services and spiritual awakenings, West Hartford approached the issue of immoral men with a modern hand. Campaigns, data, surveys, efficiency language, and committees were abundant and they reflected the atmosphere of the Progressive Era, which had normalized the idea that social problems were diagnosable, that reform should be planned and professional, and that institutions could mold citizens.

The local YMCA immediately began“fixing” up the building they had leased and they elected George B. Thayer as their new president. Thayer is one of the most interesting people in our history, in my opinion. He was a newspaper reporter, practicing lawyer, and embarked on several “adventures” in his later life. He conducted several walking tours throughout the U.S. and Europe and a few years after his stint in West Hartford, he served as a YMCA worker in France after World War I. Apparently, he went overseas to the frontline in 1914 as an observer solo and lived to tell the tale. He was already well-known for his 1880s bicycle trip from Hartford to San Francisco and served in the Spanish-American War. He was a physical education teacher to thousands of West Hartford schoolchildren and was arguably the most representative member of the gymnasium movement here.

Taking up the role as physical director of the YMCA, Charles Gleason of Westland Avenue, assistant naval inspector, hosted meetings at his home to outline the work for that first winter.

It was immediately apparent to people that it was a bit unfair that only the men were receiving considerable attention in new organizations. It wasn’t just the YMCA; there was also a Boys Brigade and the Boy Scouts.

On Jan. 8, 1913, it was noted that “little is done for girls.” Almost in response, groups of active residents collaborated to form their own organizations for young women. The Always Welcome Club was organized at St. James’s Church for both sexes, but was made up mainly of girls and so they formed a new group called the Camp Fire Girls of America. “The law of the organization is, seek beauty, be trustworthy, give service, hold onto health, be happy, pursue knowledge, and glorify work.”

The Ladies’ Auxiliary of the YMCA also played a role in the social dynamics of the day. When the new building was finally furnished and threw open its doors at the end of January 1913, the Ladies Auxiliary had a social time there sewing and playing pool.

The first year was mainly about establishment and settling down in the new space. The fun would start the upcoming fall of 1913. The YMCA branch relied on legitimacy to maintain support, both socially and financially. Their second annual report in 1914 admitted very freely that ventures of this kind often failed and that they needed to prove to donors, civic leaders, and even skeptics who wondered why West Hartford “needed” a YMCA.

The attendance was high though! Older, established citizens were paying for the institution and the features of the rooms. Membership had doubled in the spring under the leadership of two stewards. In the first year of its organization, 81 individuals gave over $1,000, which was used chiefly in fitting up the rooms. About 30 individuals pledged $270 for the second and third years.

Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Despite the idea of this branch and its rooms on North Main Street as a source of entertainment and amusement, the overarching atmosphere was still very religious and framed as morals building. There were Wednesday evening suppers with Bible talks under the auspices of the Religious Work Committee chaired by Bayard York. A dozen and a half meetings had an average of 15 young men, with a mission to explicitly reach out to men not in church or Bible schools. The YMCA positioned itself as a bridge for men who felt out of place in Sunday schools, worked irregular hours, and wanted religion without overt piety. In other words, they could play pool and hang out with their friends without the feeling of being supervised by the church leaders.

The older members of the church who endorsed this organization fell in with the strategy of the late Social Gospel: that religion had to be compatible with modern schedules and modern solutions. As a result, they provided adult education outside formal schooling. They hosted illustrated lectures on weather and travel, speakers from federal agencies (like the U.S. Weather Bureau), and supported operations by the educational work committee in bringing scientific and worldly studies to the hall.

One of the things that the Progressive Era really got right was capitalizing on the interest in the world to bring expert knowledge to people in their formative years. Beyond the boredom and monotony of school (how could someone working in a bustling office or factory feel interested in something forced into the curriculum?), the education was brought to them in their place of entertainment without the need for overtly political discussion.

To be moral, it wasn’t enough to learn about the world. These young men were encouraged to practice the idea that their bodies had to be trained and built over time. It seems like common sense to envision a well-rounded person also focusing on their physical fitness, but before this era, masculinity was considered self-controlled, independent, and morally upright. Churches basically assumed that adult men would regulate themselves; criminal behavior and urban forms of leisure destroyed this idea. It made people sick to watch young men stumble down the roads from Hartford, drunk and dirty. Brothels were frequented and gambling dens, even close to home, dismantled the moral assumptions of the age.

To help foster the physical development and scientific masculinity that the YMCA advanced, they opened up gymnasium classes in the old Town Hall and regimented medical exams by the local doctor. The gymnasium opened in the old Town Hall (then located at the old Congregational Church building on the northwest corner in the Center) on Nov. 1, 1913 under physical director Charles Gleason, assisted by W. Edward Hawley and Robert Claughsey, who served as class leaders. With physical discipline and training, the YMCA could model a man who could be healthy, competitive, respectable, and religious (but not devotional). Unfortunately, this same ideology produced men who believed that when World War I broke out in 1914, it would be easily controllable. They were not ready for the industrialized death, prolonged vulnerability in the trenches, the loss of bodily control, and emotional overload.

The gymnasium located at the old Town Hall (former Congregational Church). Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

The photograph of the gym equipment, taken in the winter of 1913-1914, is very telling about what kind of strength mattered to the organization (and by extension, to young men). Modern weight training was not the emphasis; the gym had parallel bars, a pommel horse, Indian clubs, medicine balls, and climbing ropes. This is much more indicative of a turn-of-the-century gymnastic culture, in which strength was about balance and coordination, not hypertrophy training. This was about training to be efficient and rhythmic, not intimidating and arguably violent. Strength was something to be administered, not unleashed. And like all well-rounded people, they were encouraged to head across the street and feel comfortable in a home-like environment at the YMCA hall.

The YMCA trained men to be away from rowdy public life and women contributed items to the space to produce that atmosphere. The parlor had a piano, meant for hymns and organized singing during communal events. There were no couches (those were for slouchers!) and there certainly wasn’t any intimacy between the two sexes who occupied the rooms separately. These were teenagers away from home though and the lack of intimacy is almost certainly not a guarantee.

Beyond the gym, the guest speakers, the Bible study, and the moral education, the core attraction for the YMCA branch during this era was the social life and the games. It never would have succeeded without the allure of blowing off some steam amid some friendly competition with peers in West Hartford. Bowling became the perfect game: it was indoors, allowed competition, and rewarded skill and repetition over strength.

The Congregational Church in town formed a bowling league a year before the YMCA did, but they followed their lead and added two duckpin alleys to the hall on North Main Street in 1913. Almost immediately, teams were organized a nine-team tournament was held in November, involving a hundred players. The teams included the Glee Club, Men’s Union, St. James’s, Fountain Hose Company (the fire department), Florists, Lucky Fifteen, Tennis Club, Mohicans, and YMCA. The Mohicans won the first tournament and proudly displayed their pennant, which can be seen in the featured photo. Paul Korder won the second tournament in 1914 (and three years later, he was at the training camp in Massachusetts preparing to head overseas.

Baseball was seasonal and football and boxing were too violent; bowling appealed to skilled workers and professionals, perfect for the middle-class suburban growth West Hartford was experiencing. Team bowling leagues, alongside basketball, underpinned the culture in town for years to come.

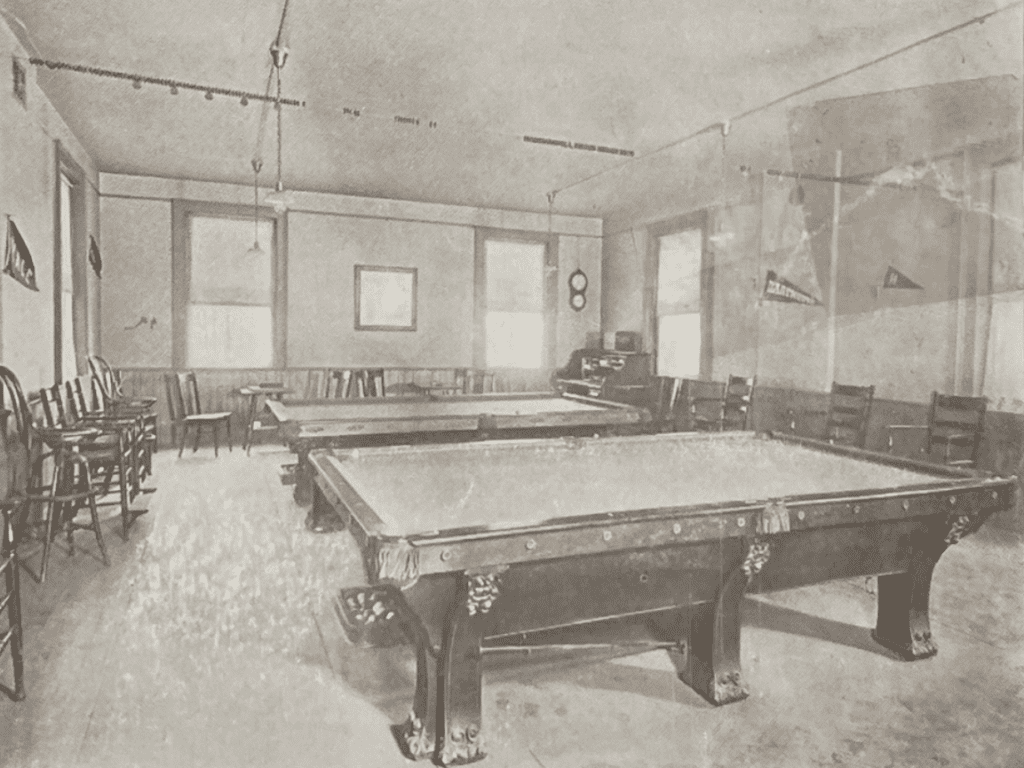

Billiards tables in the YMCA rooms. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Finally, the last feature of the YMCA rooms was the billiards tables. Long associated with saloons and taverns, gambling, and “criminal elements,” it allowed the group to engage in more fun that could be restrained. It was one of the first games introduced to the hall in February 1913 and the Ladies’ Auxiliary used these tables almost immediately, just two weeks after it opened. Multiple tournaments were held in the first year, with Henry Kottenhoff winning the pool tournament in 1914. He had worked for Allen B. Judd’s drug store not far from the YMCA hall and later founded the Kottenhoff Drug Stores, of which he was president for three decades until his death in 1969.

Within a few years, the organization added shuffleboard and other games to the hall. They bought a large electric sign for the front of the building in 1915 and added cooking utensils. The following year, more bowling alleys were added to the basement.

When the U.S. got involved in World War I in 1917, the games continued but operations became decidedly more patriotic and war-oriented. The YMCA became a morale organization for soldiers and worked alongside the government in fundraising.

After the war ended, the values of the local branch of the YMCA dispersed and moved into schools, workplaces, recreational sports, and public health. The pre-war YMCA represents the high-water mark of a belief that men could be trained and provided spaces to reach maturity. This pre-war civic revival shaped the formative years of men and women learning their place in a world that would change a lot very soon.

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.