From the West Hartford Archives: Motorcycle Officer Richard O’Meara

Audio By Carbonatix

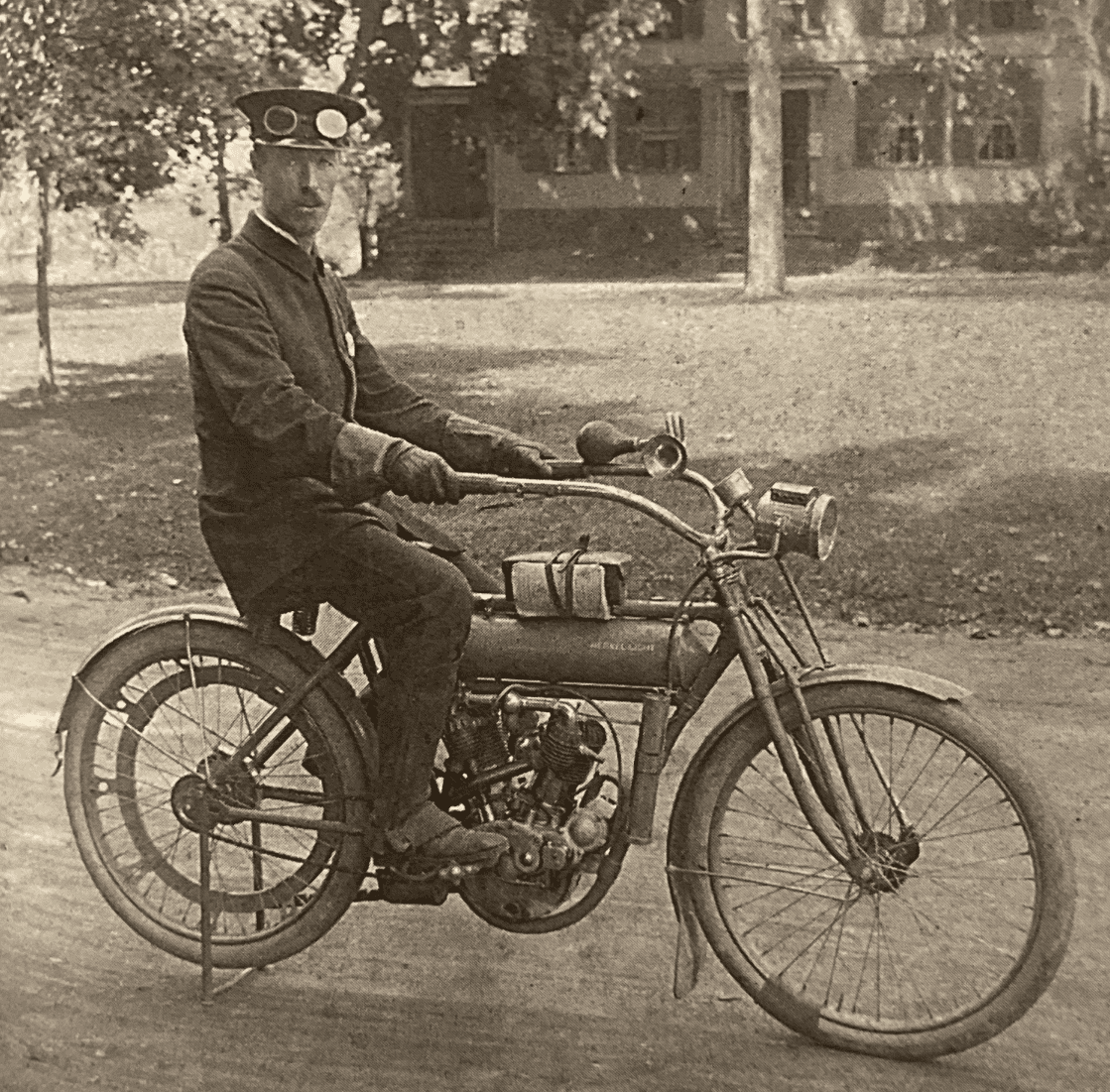

Richard O'Meara in 1910. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

Richard E. O’Meara was West Hartford’s first motorcycle officer and one of the first constables in this town hired before the organization of the regular police department. This photograph was taken in 1910. His life serves as a historical case study of the living conditions surrounding Irish immigrants, balancing labor, family, and public service.

O’Meara was born in 1871 in New York as the son of Irish immigrants, Jeremiah and Mary. They moved to New York from Ireland around 1864 after she had their first daughter, also Mary, in the homeland. There, she gave birth to Margaret, John, Richard in 1871, and then Maurice. Richard’s father Jeremiah died when he was only a few years old, prompting the family to move to Village Street in Hartford.

They rented from Irish owners in a neighborhood of tenement housing. A widowed Irish immigrant woman with five children under the age of 20 meant that the eldest daughter had to pick up some slack. She worked as a dressmaker in her teens, helping to provide for the family. Many Irish girls worked as maids, laundresses, cooks, or in textile factories, especially the mills that dotted the New England landscape. In many cases, these were among the few jobs open to immigrant women with little formal education.

As Richard grew up in this area through the 1880s, he became very active in local music culture. He was a part of the Connecticut Fifers and Drummers Association since 1884 and took part in the first annual convention of the association with the Major Allan Corps in New Haven the following year. He joined the cathedral choir of the Church of Our Lady of Sorrows in Parkville. He was a lifelong singer, which was featured in many articles throughout his time here. He was also a performer and an entertainer at heart. He performed in traveling vaudeville shows and participated in comedic shows up until the day he died.

When he came of age in the early 1890s, the family moved to Zion Street, at which point he got a job at Pratt & Whitney as a tooling machinist. His mother worked as a washer, following the trade of the many Irish immigrants before her.

Richard was appointed at the age of 21 as a fire department substitute in Hartford, hinting at a future in public service, but his primary identity throughout the decade was that of a machinist, tied to the city’s growing industrial base. For a time in the 1890s, he served in the U.S. Navy and apparently saw much of the world during his time. At one point, he was on the USS Maine, which later was sunk by a mysterious explosion that was blamed on Spain and served as the catalyst for the Spanish-American War in 1898. Thankfully, he wasn’t there when it happened.

Back home, he served in the Connecticut National Guard in Company H and was always active in athletics and music. He continued to sing in choirs and at company events. After his older sister Margaret married, the family moved in with them on Chestnut Street.

Within a few years, Richard was attending his own wedding. He married Loretta Barrett, who had been born in Pennsylvania and had moved to Hartford with her family when she was younger; her mother was also widowed. Her house on Heath Street off Park Street was not too far from Prospect Avenue in West Hartford, where the O’Mearas would build their life together. The wedding took place in Parkville on Oct. 16, 1901 at 9 a.m. The maid of the honor was his niece, the young daughter of his sister, and his best man was his cousin on his mother’s side. A wedding breakfast was served at the bride’s family home and then the couple left for a trip to the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

A month before, President William McKinley died of his wounds after being shot by an anarchist while attending the exposition. Newly inaugurated Theodore Roosevelt was at the helm when O’Meara returned with his wife on Nov. 1, 1901. For a few years after, they lived at the Barrett house while he worked a number of jobs. He was an insurance agent, then a machinist at Cushman-Chuck Company.

In 1904, the couple moved to West Hartford, taking up residence at 43 Prospect Avenue. Within a year, they had their first child, a daughter Mildred, and a new work opportunity opened up.

The Chatford Company had just opened Luna Park, the Coney Island-style amusement park on New Park Avenue, and the town mobilized a force of special constables from Hartford to police the grounds under the supervision of Officer Strong. Policing in West Hartford had been relatively quiet up until this point, besides the rare bouts of industrial strife and personal entanglements. The opening of the park brought on a wave of pickpocketing and illegal vendors fighting their way to the money that came from transporting thousands of people to and from the park every day. Popcorn and peanut vendors sold all along New Park Avenue and were found guilty of trespassing. An escaped prisoner was found hanging around the park and arrested. Officer Strong was kicked by a former employee of the park after a fight. This was all in the first month!

The following week, the town appointed five additional constables to rein in the chaos. Richard O’Meara was one of those constables to be appointed and he was thrown into the deep end quite early with this experience. He was working as a machinist at Cushman-Chuck by this point, but this extra work opportunity tied him to public service in West Hartford for the rest of his life.

The area of Prospect Avenue where they lived from the early 1900s to 1916 between Levesque and Boulanger Avenues

Google Street View

After the initial chaos of Luna Park, he qualified as regular constable in West Hartford in 1908, five months after his mother died. His brother passed a few years later. These years marked an era of personal loss for Richard, but it was also his most active in the police force when he was appointed to serve the neighborhood he lived in.

Prospect Avenue and New Park Avenue were surely not quiet areas of town, but with the perspective of an officer, he bore witness to the grittier side of town, beyond the tales of the newspapers. One of his first arrests was of a French-Canadian neighbor, charged with an attempt to sexually assault his 14-year-old daughter after her mother died. His excuse was that he was drunk and couldn’t control himself. This arrest marked the first of many for drunkenness. Another neighbor on Boulanger Avenue was physically abusing his 10-year-old son when he was drunk. Perhaps Richard’s presence in the most active section of town besides the Center made him qualified to be the only full-time policeman at the Connecticut State Fair in 1909.

But it was also not a coincidence that the American of Irish descent had landed a spot in the early police force in West Hartford. The Irish were disproportionately represented in early U.S. police forces. Waves of immigrants had arrived in the U.S. during and after the Great Famine, well into the 1850s. Many settled in urban centers, like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago, where police departments were just forming or expanding to manage the population growth.

Irish immigrants became a natural pool of candidates for city jobs, mainly in police and fire, in exchange for the political loyalty and votes of large political machines. They arrived many years before the waves of Italians and therefore networks of police and fire departments in the City of Hartford were stocked by the 1880s. His brother John, who died in 1912, was a member of the Hartford Fire Department.

Richard O’Meara may not have been given the job by nepotism, but his role in policing was yet another example of the Irish cultural influence on our local institutions. West Hartford police and fire departments were established early on with clear Irish roots.

In 1910, he was hired by the selectmen of West Hartford to become the first motorcycle officer to patrol the main roads and regulate automobile traffic. Cars were becoming all too common and the town’s suburbs were expanding rapidly. It wasn’t feasible anymore to walk all of the streets and it wasn’t frugal enough to splurge on a dozen police autos. In the late spring, O’Meara tested out a few “speeders” on the main roads, but ended up with the new “Merkle,” capable of high speed. In fact, this motorcycle that he received in 1910 is the one he is riding in the featured photo.

His primary job was that of a machinist at a machine shop; it was probably just as, if not more, dangerous than riding the motorcycle, but I’m sure speeding along the roads catching bad guys was much more exciting. The next few years saw the most action in town policing history until the 1930s. He ran it for 22,000 miles in less than two years and was often seen chasing down speeding automobiles along Farmington Avenue through West Hartford Center. In more cases than none, those speeders led him on town-wide chases, confident they could outrun him and his motorcycle.

In 1911, he took a bad fall while riding out on New Park Avenue, but was back on the motorcycle in less than a month. His worst accident came on June 23, 1912 though. He was chasing a speeding driver around the bend at Corbin’s Corner and crashed into a car at high speed. The doctor brought him home to Prospect Avenue, where O’Meara told him he couldn’t even read the number on his house.

He stayed home while he recovered, joined by his five children. Over the next decade, his wife would have three more. Within just a few months, Richard was back on the road.

He also expanded his duties in civic service. He was appointed to the board of tax relief and was more involved in politics. In 1913, he helped pull off the most successful liquor raid in West Hartford in the Charter Oak brickyard district. Two cars with officers left the town hall at 11 a.m. and the raid was made on one of the Italian houses on New Park Avenue, recovering 129 bottles, a barrel of wine, and a bottle of cider, along with a case of wine at another boarding house on Talcott Road. He had helped gather the evidence over the previous few weeks.

The town looked for new ways to organize the police force in order to counter the crime that continued to surge. It was voted to install telephones in the houses of all of the qualified constables and to give them a salary in addition to the normal fees they had earned before. As constable, O’Meara was expected to quell disturbances and keep the peace, but he was not obligated to make arrests, which would add expense to the town by bringing cases before the courts.

In the meantime, the action continued for Constable O’Meara. In 1914, he arrested a man for attempted murder of his brother. He raided a brothel in West Hartford, the so-called “Madame Karl” house. He chased a speeding car with a New York plate over four miles, in which several complicated accidents were narrowly averted. At the end of 1914, he skid in the sand on South Quaker Lane and broke his right ankle, his second serious injury in two years. He was, of course, back at it when the Connecticut Fair opened. He led a special force outside the fairgrounds on motorcycles.

His severe ankle injury prevented him from carrying out many other duties though and while he took part in gambling raids and chases, his injury pushed him to retire from the force. In 1916, after the couple celebrated their 15th anniversary, the family decided to move out of West Hartford. They moved to Capitol Avenue in Hartford, where he continued his primary job as inspector for the Royal Typewriter Company, a job he held through 1923. He sold Watkins products door to door in the 1920s and worked for Gray Telephone for a few years, stamping presses to shape metal components.

By the mid-1920s, the family was back in West Hartford, this time on Park Road but not far from the Prospect Avenue house. Tragedy struck in 1928 though when his oldest son, Edward, took his own life. Edward had served in the Navy and faced mental health struggles after he was discharged in 1921. He was unable to find steady employment, especially without the safety nets available to veterans that would be afforded them after the next world war. This period predated the Great Depression, but already saw economic volatility for working-class veterans competing for jobs in a slowing post-war economy. He had been acting “peculiarly” in the summer of 1928 and suffered a breakdown while he was drinking and in possession of a firearm. A police officer in Hartford attempted to disarm him, but Edward shot him in the leg. He turned and wounded two others before fleeing the scene and taking his own life. Edward had lived with his father at the time.

This was devastating news, but it seems Richard continued to bury himself in his work. In 1930, on top of his job in charge of the tool crib at an adding machine factory, he was appointed police officer in West Hartford, his second time on the force in more than a decade.

West Hartford Police in the 1930s, marching on South Main Street. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

This time around, he was not on the motorcycle. He served mainly as traffic officer and school patrolman. He continued his active involvement in community music groups as a singer as well. In 1933, he was on school traffic duty when a stolen car occupied by a teenager past the Beach Park School driveway drove across the property before abandoning the car at the Hartford Golf Club course. I wonder how he would have compared the incident to the “glory days” two decades before.

On March 13, 1934, less than six months later, he died at his home at 212 South Highland Street. His obituary noted that he was “one of the first constables hired to police West Hartford before formation of the regular department, and the first motorcycle officer.” He was also highlighted as a “well-known singer.”

Richard’s son Richard Jr. followed in his path. He was appointed a supernumerary policeman in the spring of 1930 and appointed a regular officer in 1937. He rose through the ranks, was promoted to detective in 1952, and was appointed assistant chief of police in 1967 after 37 years. He served in this capacity until his retirement in the fall of 1973. He had been acting chief at the time of his retirement for a few months after former Chief Rush was named civilian consultant to the department.

Every article I could find emphasizes his father’s early service to the town’s early department. Another son Rex, who owned a floral business on Park Road, succeeded his father’s legacy as an entertainer and comedian too. His 2005 obituary notes “O’Meara’s love of a good joke was well-known in West Hartford … After he sold his flower shop, O’Meara remained busy as a comedian, musician, and entertainer.” The Courant wrote in 1976 that Rex was “known far and wide as the king of Connecticut’s practical jokers.”

The story of the O’Meara family through the elder Richard is a great look into generational development from early immigration to the roots that were planted right here in West Hartford. O’Meara’s life from 1871 to 1934 covers a rapidly changing America, marked by a struggle for economic stability through multiple trades, deep involvement in our local community and the establishment of its institutions, and the gritty encounters with danger and performance in a melting pot.

At a personal level, he was an entertainer in everything he did, even when he had to do what it took to provide for his family. From vaudeville to his police service, he took pride in his comedic physicality and athleticism. In the 1917 military questionnaire taken by the state to determine who was capable of fighting in World War I, he said he could ride a horse, handle a team, and ride a motorcycle. He couldn’t understand telegraphy or operate a radio, but he could handle a boat, power, and sail. He had experience in simple coastwise navigation from his time in the Navy. The question “Are you a good swimmer?” generally sees simple yes and no answers. Instead, he answered: “One of the best.”

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

I love learning about West Hartford history. Kudos to Jeff for his detailed research and interesting columns.