From the West Hartford Archives: Snow Scene

Audio By Carbonatix

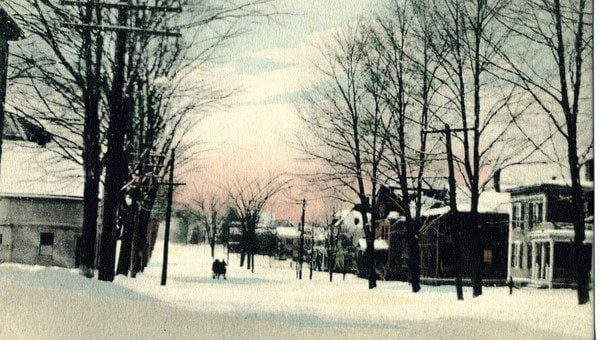

Farmington Avenue in the snow, looking west from Main Street, c.1900. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This snow scene above was photographed on Farmington Avenue west of Main Street around 1900. Snow has helped shape this town’s history, as seasonal as it is, and since we have seen some snowfall in recent days and weeks, it’s worth diving into.

Summer view of Farmington Avenue west of Main Street. Google Street view

In the era just after West Hartford’s independence from Hartford in 1854, residents were forced to simply adapt. Heavy snowfall could cut off access to Hartford, making travel difficult (although in some cases, packed snow made roads smoother and more usable for sleds and sleighs). Snowdrifts could block rail lines in Elmwood and Parkville. Families had to stockpile food, firewood, and animal fodder in preparation for the winter. Fireplaces and stoves were the primary sources of heat, but the woodlands on Talcott Mountain provided ample wood supplies.

The connection with Hartford made winter contact more difficult, but people managed. At the end of 1855, Frederick Kolenberg, a tailor who had come from Germany, fell down a snowy embankment on Pearl Street in Hartford and injured himself. About a year later, a heavy blizzard blocked one of the main roads leading into town and more than a hundred West Hartford farmers turned out with their oxen teams and a handful of shovels to open up the road.

The Farmington Avenue of old had a long row of tall trees from Prospect Avenue to Quaker Lane, but in the years after independence, it was noted that the shade prevented sunlight from reaching the dirt roads and snow and ice would last nearly all winter in a giant muddy mess. The town selectmen therefore set out to cut down a significant portion of the old trees that lined the avenue, which was appreciated at the time but lamented many years later in the inevitable bouts of nostalgia.

Snow could bind the communal spirit in West Hartford. In 1877, the West Hartford Village Improvement Society was formed in connection with the Congregational Church. Banding together, residents set out to build gravel sidewalks and wood plank driveways along the main roads. As told by William Hall, “several citizens who owned horses volunteered to keep the walks cleared of snow in the winter, with snow-ploughs drawn by horses.”

For the children and young adults, one of the joys of a snowstorm that remained the longest was the sleigh rides. Every time a layer of snow formed after a storm, the Hartford Courant’s West Hartford correspondent delighted in relaying the news that sleigh rides were being offered and turnout was excellent, even with the odd accident (in 1880, a sleigh ride from Elmwood crashed into a stone bridge, spilling the occupants into the snow and breaking the sleigh). It also helped push for infrastructure changes. In December 1883, the residents of Elmwood petitioned for a platform at the train station there. “It is hardly fair to oblige ladies to land in two feet of soft snow,” wrote the Courant.

A similar scene to the featured photo, but looking northeast to North Main Street and Farmington Avenue. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

As West Hartford grew, so did the impact of snowfall. By the 1890s, snowy weather was delaying mail and halting business with Hartford. Meetings of different organizations formed throughout town, like the different literary societies, church socials, and guest lectures, were constantly postponed during the winter. Attendance at church was noted as consistently lower right after a heavy snow.

In 1894, when the electric trolley was laid out through Farmington Avenue, a massive snowstorm caused great damage to the lines, tore apart electric wires, and stopped the cars indefinitely. This caused the most trouble in the Buena Vista area, particularly Gin Still Hill, where gangs of workers were at work on a nearly daily basis in February 1895 digging out the snow to open a route for the trolley. The “snow embargo,” as it was called, was finally lifted by the work of a hundred shovelers employed by the trolley company.

The development of more roads off the main highways forced the town to start employing a force of men just to break through big snowdrifts. Any road work, including sewer work, was halted during these times. Snowfall also led to building damage – part of the roof of the double horse sheds in the back of the Baptist Church collapsed from the weight in 1901. A house being constructed at the corner of South Highland Street and West Beacon Street was absolutely destroyed by a storm on Dec. 14, 1915.

Public schools, like today, were closed depending on how severe the weather was. Teachers often came down with the flu, measles, and other cold-related illnesses during the winter, coinciding perfectly with some of the big snow events.

Harry G. Swift, who lived on Park Road, ran a two-horse plow over several miles of sidewalk in the winter of 1901 on his own time and dime. Townspeople recognized his service by raising $15 for him as a gift (that’s about $550 today). On the other hand, Fred Gammack, who ran a poultry yard on Fern Street near North Main Street, lost a ton of money in the winter of 1913-14 because he couldn’t get his product over the road at all that winter.

The snow definitely impacted everyone differently. If trolleys alone were impacted by snow, the addition of automobiles into the 1910s sometimes caused chaos. In 1915, 10 cars were stalled out in the middle of the intersection at New Britain Avenue and South Main Street, delaying all travel for a significant amount of time. A year later, George Peterson of Fern Street became stuck in Hartford, right in the path of two trolley cars as they crashed into him; he escaped uninjured, but his car was smashed to pieces.

Many Italian immigrants in the early 2oth century, including in West Hartford, were employed by the town on road construction and maintenance. Snowy periods could be brutal – snow glare was a real concern and in fact, southern Italians (who were predominantly more likely to immigrate) were less used to prolonged snow exposure. Several Italians in the winter of 1916 experienced “snow blindness” and were considered too ill to come back out.

Skiing in West Hartford, 1948. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Over time, the government looked to improve the maintenance of the roads collectively, especially at a time when the population was growing immensely. In 1914, the town passed a sidewalk ordinance, ordering property owners to remove snow between five hours after the storm and within five hours after sunrise. Owners were encouraged to cover their sidewalks with sand or sawdust to prevent ice from forming. Violations ran up a fine of 5 dollars for each violation (for context, this is about $156 today!). Every storm had at least 3-5 offenders.

When West Hartford switched over to the town manager system of government in 1919 (away from a board of selectmen), the two most important issues were roads and schools. Town Manager Benjamin I. Miller noted that it had been a particularly rough winter and funding was difficult to secure for snow clearing labor. In the 1920s, horse-drawn wooden plows were replaced by metal plows, along with attachments for trucks. This followed Hartford’s example.

In 1923, the town did a trial run for a giant five-ton caterpillar tractor for snow plowing and after a successful test, the town sent it out on its first mission, creating a bank of snow nearly six feet tall. It was noted that it could work so much faster than horses that it could do double the work of four horses and one grader. By the end of the year, West Hartford was mentioned in the magazine “American City” as a model for snow removal.

Of course, removing snow is important, but keeping it is more enjoyable sometimes! Children have sledded, skated, and skied through the winters from the 1920s to today. Wooden sleds with metal runners were the most common for sledding beyond toboggans and horse-drawn sleigh rides continued to be popular through the 1920s. Cars and trolleys gave children and teens access to better hills.

People still debate which hills are the best spots (my 10-year-old brain still believes Wolcott Park’s to be steeper than it really is). Skating was mostly done on frozen ponds, lakes, and rivers, like at Beachland Park, Fern Park, or the old Trout Brook Ice Company’s pond off Farmington Avenue and Trout Brook Drive. Skiing wasn’t yet popular as it was still predominantly a European activity, but smaller ski clubs in New England formed through the 1930s and by the early 1940s, it was a common enough winter activity dependent on how much snow fell.

When the Town of West Hartford bought Buena Vista in 1943, they envisioned it as a “winter sports area,” setting up three ski trails. The West Hartford Outing Club helped pull together activities across the park, including skiing events. The Blizzard of 1947 on the evening of Christmas brought over 600 people to the slopes at Buena Vista on the Sunday after.

To tie it all together, some snowstorms are simply memorable to us in history. The Blizzard of 1888 was one of the most severe winter storms in American history, bringing 20-50 inches of snow to Connecticut. The Courant reported that a “young man who lives in West Hartford beyond the Center” arrived at Hartford just after noon after the storm and was “almost up to his shoulders” in snow. This might be one of the few times this wouldn’t be an exaggeration. The snow was so deep that sometimes could reach the second story of a house!

As mentioned before, the Blizzard of 1947 dumped so much snow on West Hartford that the winter athletes rejoiced and the historians compared it to the storm of ’88. A nor’easter in 1969 hit New York City the hardest (and killed nearly 100 people), but West Hartford saw plenty of snowfall. The first two months of 1978 saw multiple wet snowstorms, as well as the collapse of the Hartford Civic Center roof.

Storms hit hard in 1997 and 2003, but in recent memory, the October 2011 snowstorm will remain infamous. As a senior at Conard, I ventured out quite late with friends after a Halloween party to a completely dark and eerie Blue Back Square and then struggled for more than a week and a half in Elmwood without power. I distinctly remember still having a lot of homework though. In all, snow has given us plenty of ups and downs, but it has brought West Hartford people together in a lot of ways.

The intersection of Farmington Avenue and LaSalle Road in West Hartford Center blanketed in snow in 2018. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

I just want to thank Jeff Murray for the wonderful articles he faithfully writes about the history of West Hartford. They are informative and entertaining, but most importantly, they help us gain a greater love and appreciation for our town. Keep up the great work, Jeff.