From the West Hartford Archives: South Quaker Lane Near Boulevard

Audio By Carbonatix

South Quaker Lane, looking south towards the Boulevard, in the 1920s. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This view of South Quaker Lane, looking south towards the Boulevard, was taken in the 1920s. Each corner of this intersection was developed nearly independently, the result of very different families owning the land.

South Quaker Lane was named after the Quakers, who settled in this area of West Hartford after the 1780s. The Religious Society of Friends was founded in England in the mid-1600s, rejecting the formal clergy, creeds, and elaborate church rituals of the era. Their practices of pacifism, simplicity, equality, and refusal to swear oaths or participate in war made them a political target in England, especially during the mid-1600s.

England was deeply divided over religion and the role of the monarchy. The aftermath of the English Civil War (1642-1651) saw a breakdown of control by the Church of England and a surge of new religious groups, like the Quakers and Baptists, who challenged traditional doctrines and the authority of church and state. After the monarchy was restored in 1660, the government passed laws that targeted dissenters like Quakers. Many were imprisoned, fined, beaten, or even killed, pushing many to seek freedom in the American colonies overseas.

In 1681, the Quaker William Penn founded Pennsylvania as a haven for religious freedom and tolerance. They strongly promoted tolerance and diverse religious groups, unlike many other colonies with official churches in New England. In 1697, the colonial government of New York granted a tract of 145,000 acres in Dutchess County to nine influential men, mainly Anglican or Dutch Reformed merchants and colonial elites from New York City with ties to the British Crown. Many of the settlers who leased or bought land in Dutchess County were Quakers, attracted by the rural setting and relative tolerance in the Hudson Valley. Beyond Puritan New England (think Salem, Massachusetts, which had just had witch trials years before), Quakers were generally allowed to worship freely and build meetinghouses.

The first Quakers showed up in West Hartford around the 1780s from this New York community at a time when it was more acceptable. The American Revolution had undermined the old Puritan religious monopoly in Connecticut and weakened the authority of state-supported churches like the Congregational Church. Revolutionary ideals like liberty, freedom of religion, and personal rights were fertile ground for greater acceptance. Connecticut didn’t fully disestablish the Congregational Church until 1818, but in practice, other religious groups were tolerated more after the Revolution and more spirited Quakers sought out new roots in other states, like Connecticut and Massachusetts.

The most prominent Quaker family in West Hartford was the Gilberts, which purchased an acre of land on the east side of Quaker Lane. A small cemetery was laid out on this land, part of a large farm owned by brothers Charles and Elisha Gilbert. A meetinghouse and schoolhouse were built next to it. As William Hall tells it in his book, some members of the Congregational Church even joined the Quakers and were charged with heresy.

The Quaker meetinghouse was the site of the first services of St. James’s Episcopal in the 1840s and it was purchased a decade later by the Gilbert family, which converted it into a house and moved it to North Quaker Lane, where it ultimately burned down. Over the late 1800s, the Quaker land was steadily sold until the area around the cemetery was owned by the Foster family, namely Emma Phelps Foster (1851-1942).

In 1911, Weston W. Walker, proprietor of the Boston Branch Grocery, purchased 18 acres along Boulevard west of Whiting Lane from Henry Owens and began planning three new houses. A year later, Walker bought the land between the Quaker cemetery and the Boulevard from Emma Foster for further development. Walker focused mainly on the south side of the Boulevard, leaving the northern side mainly intact but open for sale. In fact, in the featured photo, a Walker real estate sign can be seen at the left.

A few years after Walker’s development opened, the rest of the land on the east side of South Quaker Lane was sold to a real estate company and Maplewood Avenue was laid out. Years later, Maplewood Avenue would be extended through Walker’s land to connect with the Boulevard but until then, it would be a dead-end street that stopped at the rear of the Quaker burial ground. On the south side of the Boulevard, Walker’s land ended at the rear of what became Washington Circle.

In 1913, he and his son sold the store and focused on the development along the Boulevard until his retirement. He laid out Forest Road west from Whiting Lane and had a house built for occupation at #11, where he died in 1938. One of the owners of a house he oversaw on the Boulevard was the secretary-treasurer of Walker’s grocery store, Thomas Mills. In 1927, Mills opened a Boston Branch Grocery store in West Hartford Center at 967 Farmington Avenue.

The northwest corner of South Quaker Lane and Boulevard was tied in with the Busch family, who were not Quakers. Peter H. Busch was born in 1831 in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany and married Anna Zimmermann in the fall of 1859. After the campaigns of Napoleon, his hometown became part of the Kingdom of Prussia, known for its rigid bureaucracy and centralization. The area rapidly industrialized and grew. Economic, political, and social pressures after the Revolutions of 1848 led many in this region to emigrate, especially to the U.S. The 1850s saw a surge in German immigrants, especially from Prussian territories like this one. West Hartford saw several German arrivals specifically due to the Revolutions.

Busch, however, arrived in the U.S. much later. In 1871, the German Empire was formed under Prussian leadership, uniting various German states after a series of wars. A long economic depression a few years later, triggered by the Panic of 1873, affected North Rhine-Westphalia’s economy, especially textile exports. Unemployment and economic stagnation pushed many laborers to emigrate. Busch took his family to the U.S. in 1882 after years of economic downturn, religious suppression in the empire, and overpopulation. They sailed from Antwerp, Belgium, on a passenger steamship named after a German-American piano magnate. He worked as a carpenter in Hartford through the 1880s and then settled along the west side of South Quaker Lane in 1885. This move fundamentally changed the trajectory of this section of town.

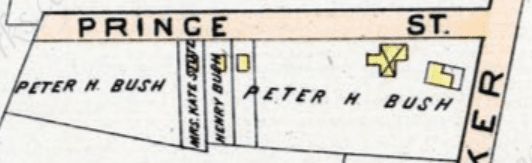

Map of South Quaker Lane and Kingswood Road in 1896, showing the Busch development

Peter and his son Henry, who followed his father’s trade, built a carpentry shop here in 1894. They also constructed a number of houses along South Quaker Lane that prompted them to consider expanding. The electric trolley had just been established along Farmington Avenue and landowners in this vicinity were salivating at the idea of laying out subdivisions to capitalize on the incoming wave of suburban growth.

In 1895, Niles White had laid out Outlook Avenue on the west end of this property and the Busch family collaborated with him to open a road of their own to connect the two – they called it Prince Street (it was later renamed to the current Kingswood Road). Over the next five years, the Busch family expanded as cousins arrived and moved to Prince Street. Occupants of these houses came and went though. Fires burned through multiple houses and absences were constant. Simon Busch served in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Peter Busch, in his 60s, moved to Belgium for a short period of time. The Busch family became a great window into global events at the beginning of the 1900s for people in West Hartford.

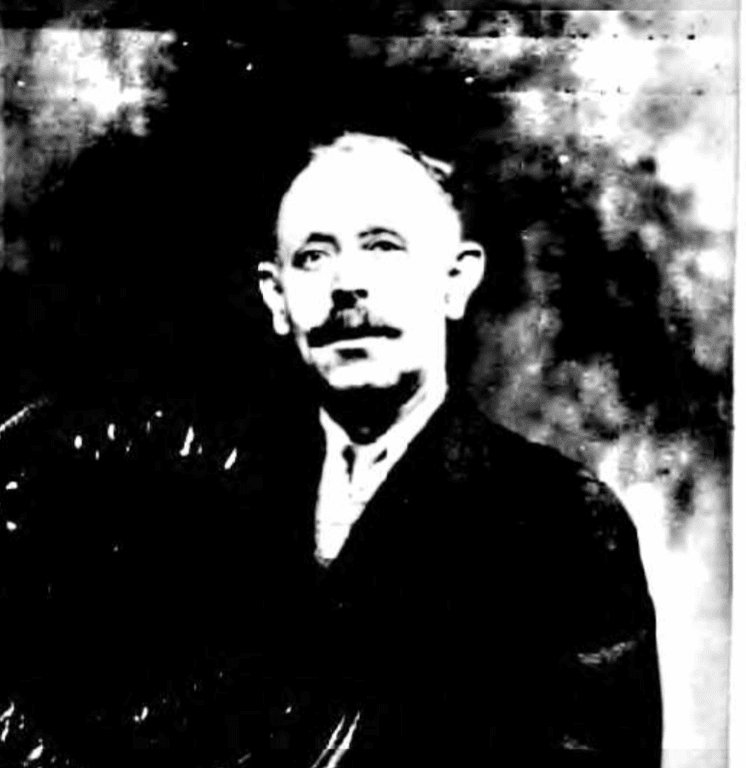

In 1902, Henry Busch left his family home in West Hartford to move to Siberia to assist in the construction of a railway. The Russian Empire was nearing the completion of the Trans-Siberian Railway, a massive project linking Moscow to Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean, the largest infrastructure development in the empire. It drew thousands of foreign specialists, like engineers, contractors, tradesmen, and entrepreneurs. Russia recruited skilled workers, including many German-Americans, to help build stations, factories, housing, and infrastructure at various stops along the railway.

For the time being, it didn’t make sense to bring the family. Conditions in Siberia were too rough and unstable for families and this contract was temporary and lucrative. Unfortunately, he couldn’t predict the future and within just a few years of his relocation to Siberia, war broke out between Russia and Japan over control of Korea and Manchuria. Vladivostok, where Henry had settled for his contract, was a strategic military port and civilian movement was severely restricted. He attempted to leave the city and come back to West Hartford, but he was forced to stay, as it was under partial naval blockade and travel was restricted.

West Hartford history has no shortage of locals like Henry who were caught in the crosshairs of empires, in this case Czarist Russia and rising Japan. In September 1905, President Roosevelt mediated a peace agreement between the two powers at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Maine. Henry was not only able to return home at the end of 1905, but he almost immediately went back, this time with his family for a few more years to oversee the operations of a sawmill in a region undergoing postwar reconstruction. Maybe they figured they should all be together if chaos were to break out again.

Henry Busch’s passport photo, early 1920s Photo Credit: National Archives and Records Administration

In the summer of 1908, the Busch family left Vladivostok and crossed into Japan, boarding a steamship at the port of Kobe and traveled across the Pacific to Seattle, taking the train across the country to Connecticut. This time, they left West Hartford entirely and moved to Bristol.

A few years later, the elder Busch, Peter, died in West Hartford, leaving the siblings on Kingswood Road and South Quaker Lane. Joseph Busch, who lived at one of the older Busch houses at 155 South Quaker Lane, served as the chairman of the newly organized Quaker Fire Brigade in the 1910s; meetings of this brigade were held at his grocery store.

By 1920, the west side of South Quaker Lane was almost entirely developed. Most of the land north of the Busch holdings was sold off to a real estate company that laid out Lancaster Road, Garden Lane, High Street, and Ware Avenue. Most of the Busch family moved out of West Hartford by the early 1940s and are mostly forgotten in West Hartford history beyond the obsessions of researchers. Kingswood Road owes its existence to this clan though.

Finally, an analysis of the featured photo would be incomplete without mentioning the church in the right background. Today, the southwest corner of South Quaker Lane and Boulevard consists of brick apartments, but in the 1920s, this was an open block with a small church building in the middle.

On Nov. 4, 1920, the Church of St. Thomas the Apostle was established, with Rev. John F. Callahan as its first pastor. New parishes were formed in the Hartford area mainly as a result of increased immigration. Large numbers of Catholics from Ireland, Italy, Poland, Germany, and other parts of Europe immigrated to the U.S., settling in Hartford and suburbs like West Hartford. The Church of St. Brigid was the first Catholic church to be built in this town, but it served the residents of Elmwood, centered along New Britain Avenue. St. Thomas the Apostle was formed a few years later to serve Catholics north of Elmwood.

Work immediately began on a chapel on the Boulevard and South Quaker Lane, similar to those constructed recently in Newington and Burnside in East Hartford. It was used as a temporary building for the parish, with Rev. Callahan living across the street from Jessamine Street in the rectory. The first census taken of the parish showed 600 men, women, and children. In November 1923, the church bought land on the north side of Farmington Avenue and Dover Road. Work on a brand new church, a more permanent structure, was started in 1925. For many years, the parish met in a basement church here starting in 1926 – funds were limited, demand was immediate, and expansion was part of the long-term plan.

Monsignor Callahan devoted more than 50 years to the priesthood and had been with the parish since its foundation in 1920 when he oversaw the dedication of the current completed church building in September 1951. Construction had been delayed by the Great Depression and World War II, but work went ahead in 1950 over the top of the basement church on Farmington Avenue.

Callahan was given the title of Monsignor by Pope Pius XII in 1946. Pius XII was the head of the Catholic Church from 1939 to 1958, leading global Catholics through World War II and the early Cold War era. The Catholic Church in America was booming after the war due to returning GIs, the baby boom, expanding suburbs (especially in West Hartford) and increased immigration.

The temporary structure on South Quaker Lane was long gone by this point. In fact, this corner, once the wooden chapel was torn down, was simply empty grassland for more than 20 years.

In the late spring of 1954, excavation began for a series of garden apartments here, developed by attorney Joseph X. Friedman and contractor Bernard I. Friedman who bought the land from St. Thomas the Apostle Church in November 1953 and received approval for garden apartments at this corner. The Friedmans owned several apartments in West Hartford and this one was no different. “Boulevard Manor,” as it became known, rented out for $125 a month.

The same factors that swelled Catholic participation to allow for construction of the new church on Farmington Avenue also made garden apartments on the old site very popular. They were quick to build and could house many people affordably; returning veterans and the baby boom prompted a severe housing shortages, especially for young families and working-class households. By the early 1950s, many people were leaving Hartford for West Hartford. The Federal Housing Administration provided favorable financing for builders of multi-family rentals. Garden apartments fit the model of “decent, safe housing” promoted by the federal government.

The featured photograph taken in the 1920s gives us a lot to think about. The Quakers had set the stage for the area’s settlement and then it became a sandbox for wealthy developers, immigrant contractors, and more modern religious roots. The history of this town is a perfect window into how connected we all are to the world around us.

South Quaker Lane looking south to Boulevard. Google Street view

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.