From the West Hartford Archives: South Seas Restaurant

Audio By Carbonatix

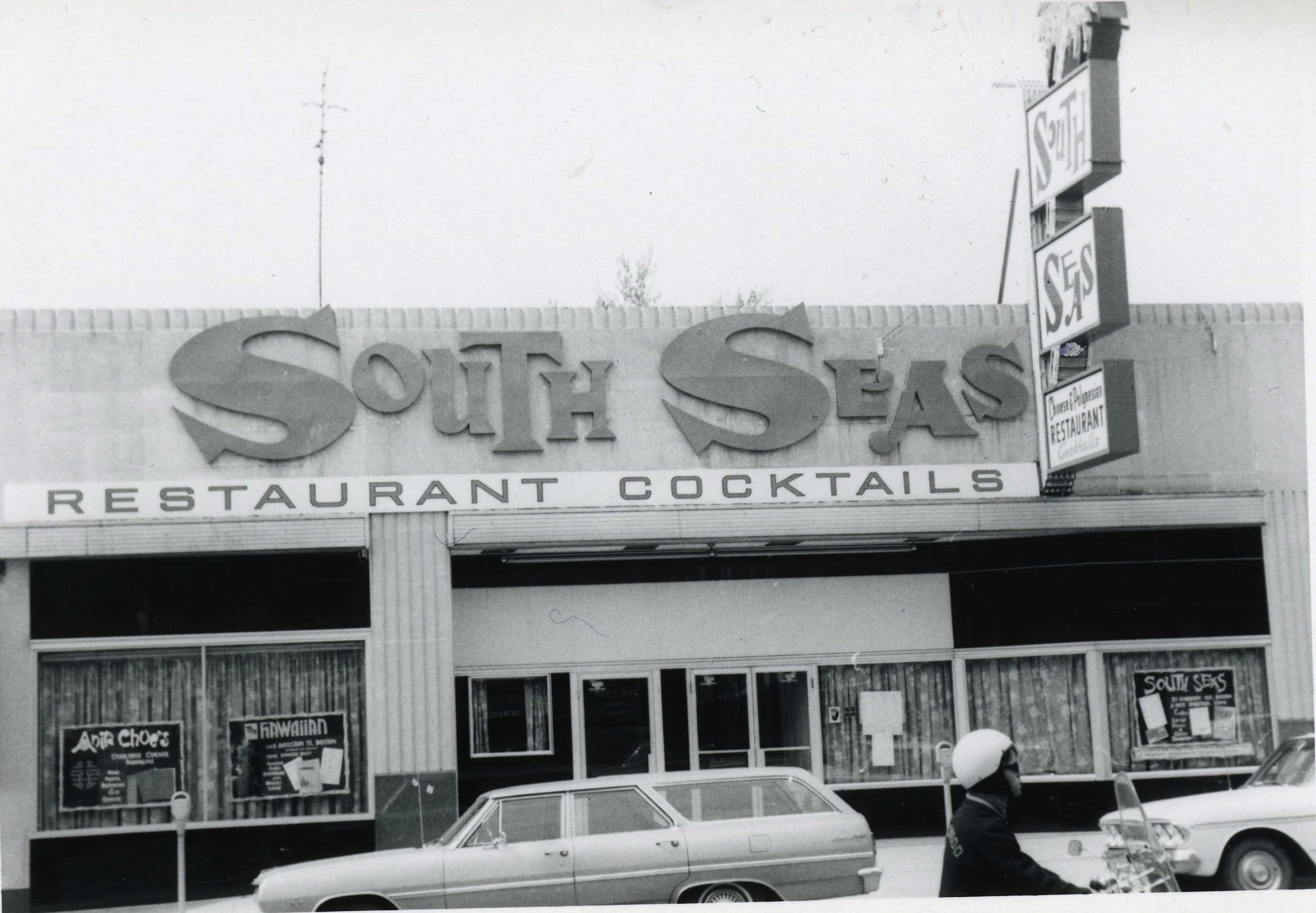

South Seas Restaurant, 964 Farmington Ave., West Hartford, 1966. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The South Seas Restaurant opened at 964 Farmington Avenue in the fall of 1961. The opening writeup in the Hartford Courant noted: “This unusual and authentically Polynesian–Cantonese restaurant, with its tropical décor and Island rhythms, recreates a true touch of Polynesia in Hartford.” It was modeled after the restaurant’s successful Boston location, which had been opened in 1958 by the same owner, Henry Oi. This photograph was taken in 1966.

Tiki culture in America traces its origins back to the 1930s, but its influences go back to a romanticized Western perception of the South Pacific as early as the 1900s when Hawaii and the Philippines were made colonies. The first Tiki-themed bars and restaurants opened in the late 1930s in Los Angeles, inspired by trips to the South Pacific that brought a vision of island culture, rum cocktails, and tropical décor.

Restaurants into the early 1940s placed greater emphasis on food, particularly Chinese and Hawaiian fusion dishes. Trader Vic’s, which laid claim to the Mai Tai in 1944 and expanded into an international chain from its roots in Oakland, California, helped solidify the Polynesian restaurant aesthetic. During World War II, thousands of American soldiers were stationed in the South Pacific, particularly in Hawaii, the Philippines, and various Polynesian islands. Upon returning home at the end of 1945, many veterans brought back fond memories of island life, exotic drinks, and Pacific culture, although it was still largely through Western eyes.

Hawaii played a crucial role in the rise of Tiki culture and Polynesian-themed restaurants though. The attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 placed the Hawaiian islands at the forefront of American consciousness and throughout the war, thousands of American soldiers and sailors were stationed there and exposed to pineapple, kalua pork, poi, steel guitar and hula performances, and tropical landscapes. Many soldiers simply viewed Hawaii as an exotic paradise far removed from the horrors of war and returning servicemen brought back a longing for “island life.”

After the war, Hawaii became a symbol of postwar escapism and leisure. Before Hawaii even became a state, it was already a major travel destination. Matson Cruise Lines and airlines like Pan American Airways promoted Hawaiian vacations for wealthy mainlanders. Pineapple plantations and sugarcane fields were heavily marketed and hotels and restaurants capitalized on this fantasy with Tiki-themed drinks, hula dancing, bamboo, statues, and waterfalls. “South Seas” restaurants popped up across the U.S., fueled by Hollywood films and club advertising.

In 1958, Henry Oi, who was born in China, opened a South Seas in Boston. In fact, Chinese-American entrepreneurs had a knack for leaning into “exotic” branding to attract non-Chinese customers in the United States by blending Cantonese cooking with Tiki branding. Oi also came of age during a time when Chinese Americans faced significant discrimination, as the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882-1943) was still in effect. As a result, job opportunities were limited to industries like laundries, grocery stores, and restaurants.

He moved to the United States from rural China in the late 1930s and was a lodger in Boston, making a living as a waiter in restaurants. In 1942, he enlisted in the Army and served overseas in the Army Air Corps. After the war, Oi returned to Boston and worked his way up to head waiter at a restaurant in the city by the early 1950s.

The opening of the South Seas in Boston in 1958 was timed quite well – many Tiki restaurants already used Cantonese-style cooking and Polynesian restaurants were more socially acceptable than explicitly Chinese restaurants at the time. Many Americans were still skeptical of Chinese food in the 1950s and associated them with cheap “chop suey joints” (themselves an American Chinese invention). A Polynesian restaurant therefore appealed to a wider group of people.

By the 1950s, Hawaii had a strong enough economy that made it suitable for statehood (it had been a U.S. territory since 1898), as it was no longer just a remote Pacific outpost. The U.S. was under pressure to end colonial-style rule over its territories and the civil rights movement had influenced Hawaii’s push for equal treatment within the United States. Hawaii officially became the 50th state on Aug. 21, 1959, a year after Boston’s South Seas restaurant opened.

The South Seas signage in front of 964 Farmington Avenue in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Noah West House & West Hartford Historical Society

In many ways, the 1960s represented the full maturity of Polynesian-themed restaurants in the U.S. Advertisements for the West Hartford location marketed island music, private parties, luaus, and “island and Cantonese foods.” It offered barbecued spare ribs, shrimp puffs, Diamond Head fantasia (chicken, shrimp, roast pork, and vegetables), Hawaiian coconut ice cream with fortune cookies, duckling, fried rice, and Tonga beef (beef strips sauteed with greens and topped with vermicelli and shrimp chips).

Scorpion Bowls, the Pu-Pu platter, fire-glazed mugs, and little umbrellas came along for the ride in the presence of an indoor waterfall. School children were treated to “oriental” dishes after a unit on Japan. Political and civic organizations held Hawaiian-themed lunches and dinners (as I write this, I am looking at a photograph from 1964 of Young GOP members wearing leis). The West Hartford Jaycees received their charter from the estate at a banquet at the South Seas. Senior prom dinners were held there. The Royal Typewriter Girls’ Club hosted their installation of officers and then immediately headed over to South Seas for a luau in 1970.

By the 1970s, the Polynesian trend slowly but steadily lost its massive appeal. It was still very popular, but more Americans were traveling internationally, shifting more towards “authentic” experiences, and gravitating towards fast food and casual dining. The rise of McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s, and other fast-food chains helped pull away some customers.

Cocktail culture was also changing. Vodka, tequila, and whiskey were becoming more popular than rum and the disco era (including the Central Theater’s brief tenure as a disco) pushed aside elaborate Tiki drinks like Mai Tais and Zombies. As Polynesian branding declined, the South Seas adapted and began marketing itself as more Cantonese and “Szechuan.” Chinese-American restaurant owners and managers rebranded their businesses to focus on “real” Chinese food, especially at a time when customers were slowly drifting.

In 1965, the U.S. had lifted strict immigration quotas, leading to a massive influx of immigrants from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and mainland China. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Szechuan cuisine became a hot trend in American dining. South Seas had already been serving Cantonese-style food, along with the Polynesian cuisine, but the rebranding could help compete with the wave of new Chinese restaurants opening.

The mid-1980s proved to be the end though. At the end of 1986, the South Seas Lounge closed (and was followed by its sister location in New Haven closing shop as well). Nationally, the tiki theme just simply did not resonate the same with the younger generation. Some of the original Polynesian chains, like Trader Vic’s, shrunk dramatically in the 1980s. Today, the former South Seas in West Hartford Center is the location of Max Oyster Bar.

To many West Hartford residents, South Seas was their first introduction to Polynesian and Chinese food. The idea of a Chinese-American WWII veteran capitalizing on a Tiki-themed restaurant boom can tell us a lot about our history of immigration to the United States and how shifts in demographics can impact what we eat, incorporating in good ways and bad ways the people we absorb through warfare, colonization, and political trends.

The idea that certain foods start as “too foreign” but gradually become mainstream through exposure is a core part of how America’s “melting pot” identity has shaped its food culture. Even Italian foods (like garlic-heavy dishes) were considered “too smelly” for many Americans in the late 1800s. Immigrant groups bring their cuisine to the U.S. and adapt to skepticism and hesitation by creating American variants that blur the line between countries – on the one hand, some argue they take away the authentic experience of foreign foods. Others argue they help ease those into learning about different cultures and palettes.

New York-style pizza and Chicago deep dish transformed pizza from a “poor immigrant food” into a national favorite; garlic bread and giant meatballs in spaghetti; and chop suey was one of the first “accepted” Chinese dishes in the U.S. in the early 1900s (it also introduced many Americans to stir-fried cooking and soy sauce for the first time). Mexican-American restaurants crafted oversized burritos, fajitas, queso dip, and taco salad. Even some of our chips, like Doritos, were inspired by Mexican tortilla chips. California Rolls were the sushi gateway, making the idea of raw fish less intimidating over time. Mediterranean flavors came in the form of Greek gyros, sweeter fruit-flavored yogurt, and hummus as a mainstream dip. Chicken tikka masala was fashioned by South Asian cooks in the United Kingdom and made its way overseas in the 1980s after the growth of hundreds of Indian restaurants in major cities.

If the South Seas Restaurant was the big thing in West Hartford in the 1960s, it tells us that global fusion will continue to dominate our cuisine and for that, we should always look for new places to try out.

Max’s Oyster Bar. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.