From the West Hartford Archives: The 1914 Power Struggle over St. James’s Church

Audio By Carbonatix

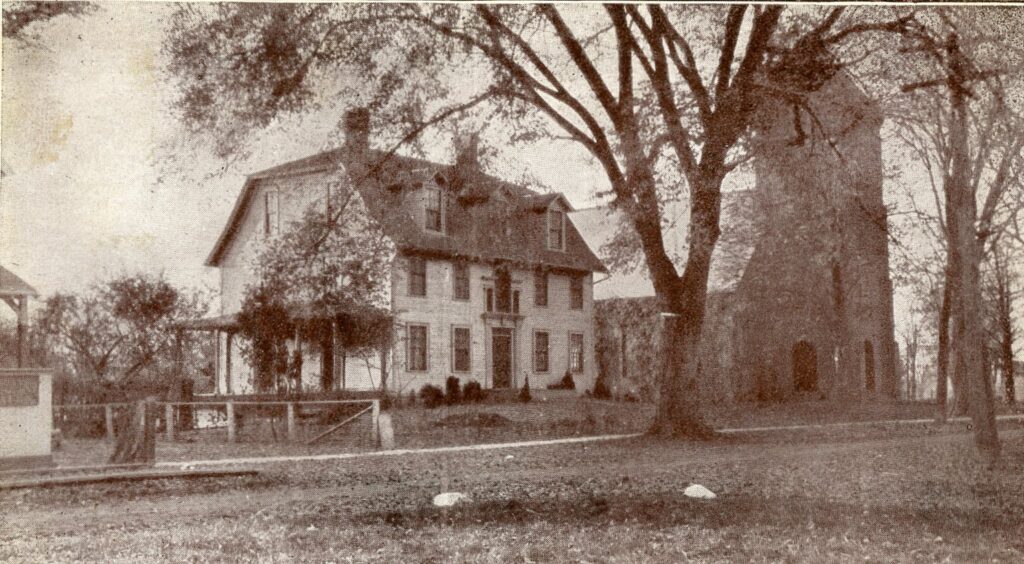

St. James's Episcopal Church in its location on the west side of South Main Street. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

St. James’s Episcopal Church, founded in 1843, was led by several rectors serving terms of just a few years through a long slow period of growth. Some of these rectors went on to become rectors in larger cities across the U.S., including in Savannah, Georgia. Others went on to teach at Trinity College, including Thomas R. Pynchon (1857-1863; 1873-1875), who became its president. William Ford Nichols (1875-1877) later became the second Bishop of California.

From humble beginnings, the church was supported financially and influentially by a few key families, including the Kelseys and Prices, but no family was more important than the Beach family after its construction on the west side of South Main Street in 1855.

Under Charles M. Beach and his four daughters Harriet, Frances, Edith, and Mary, the church was sustained for decades and was the recipient of memorials and other gifts. Harriet’s husband, William W. Huntington, also became a close supporter of the parish and served as its treasurer for nearly 40 years.

The introduction of a controversial rector would lead to one of the biggest confrontations in West Hartford’s religious history. I have told this story well if you leave this article feeling that no side was solely the reason for the breakdown in order – that everyone was responsible for the chaos that ensued in the year 1914.

The Beach family built up a considerable amount of influence over this close-knit community through the 1890s and 1900s and wielded near sole control. The parish organizations, like the St. James’s Guild, held events at the Beach’s Vine Hill Farm in Elmwood and the rectors often preached there. Finances were difficult during this time even with their sponsorship, but the church still experienced limited growth; the rectory next door to the church at 15 South Main Street underwent several renovations and the church had new electric lights installed in 1904.

Former rectors were known to stay at the Vine Hill Farm as guests after their terms, including the Rev. Joseph W. Hyde (1882-1887). After longtime rector James Gammack resigned in 1911, the parish extended the call to Harry E. Robbins, who was working in Philadelphia. While the rectory was being remodeled, Robbins was offered a stay of several weeks with his family at Vine Hill Farm, staying at the Beach house. Later he recounted that when he arrived in West Hartford, he “found St. James Church controlled by one family.”

The Beach sisters – Harriet, Frances, Edith, and Mary. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Harry Robbins was a certified Progressive when he joined West Hartford’s citizenry in 1912. He was an avid campaigner for Theodore Roosevelt’s controversial Bull Moose Party (running as a third party candidate, former Republican Roosevelt would end up splitting the vote in the 1912 election and handing the presidency to Democrat Woodrow Wilson).

As the member of a movement that emphasized an active hand in the running of affairs from the top levels of government all the way down to the local organizations, Robbins embarked on an immediate campaign to grow St. James’s Church. One of his first initiatives was to make the parish more democratic by enabling the election of a larger and more representative vestry. He found that many of the practices of the church were not as official as the Episcopal canons (rules) required, so he made an effort through 1913 to legitimize the affairs of the parish.

Outside of the running of the church, he seemed to be everywhere all at once. The Hartford Courant noted at the beginning of 1914 that he nearly tripled the interest in membership, organized countless societies for men, women, and children, and didn’t shy away from any group. He could “attend a ladies’ missionary tea in an afternoon and do his share of missionary and town gossip and bowl a first-class game on the local alleys in the evening, or hold his own in the pool tournament.” At the end of March, he was being hailed as a ray of light on his way to bringing true prosperity to a small-town church.

However, just two weeks later, the church would break out in open public conflict and by the end of 1914, Robbins would be forced to resign and driven out of West Hartford for the rest of his life. How could that happen?

To the Beach family, Robbins was a clear threat to their influence when he set about deconstructing the church affairs and remaking them in his image. His attempts to legitimize some of their practices came off as insulting. For example, Robbins pushed to better audit the collection system for church offerings to make the system more transparent, but the William W. Huntington, the Beach sisters’ brother-in-law and treasurer for 39 years, was insulted – to him, Robbins was basically accusing him of pocketing money.

How do you know if the new rector is legitimately trying to help or if he’s snooping around to undermine the support you’ve given to the small church in your town to carve his own path? It could have been both.

Trouble between Robbins and the Beach-Huntington family started before November 1913 but it was made clear in a series of letters between the two during this time and it was here that it began to spiral out of control. Robbins accused Frances Beach of not showing up to church services and attempted to strip her of her longtime title as Directress of the Chancel Guild (furnishing the space around the altar of the church). She responded by getting her hotheaded lawyer Walter Schutz involved and denying that she was missing any services.

Robbins lamented the involvement of a law office in church affairs, especially for something so small, and ignored him, prompting more communication from Schutz. A few months later, in the spring of 1914, Robbins brought up an issue to be resolved at the annual meeting – apparently the 1913 applications for membership had not been legally administered and so they had to start over now, throwing into question who was a member of the parish and who wasn’t.

The St. James’s rectory, a remodeled colonial-era house purchased by the parish from the Congregational Church. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

The showdown was set for the annual meeting on April 13, 1914. When it was called, Huntington refused to participate, leaving Robbins alone to administer newly legal applications for membership. The Beach lawyer, Walter Schutz, jumped in to object, but Robbins called for the local police to take a seat in the back and prevent Schutz from intervening. After the business meeting concluded though, Schutz once again spoke up and demanded Robbins resign as rector and hand over the parish records, including the meeting minutes. “No, I’ll give you nothing,” responded Robbins. Schutz lunged for the papers and a brawl broke out involving six to eight men. Robbins quickly adjourned the meeting and escaped to the rectory, but Schutz took over and held his own meeting to elect his own officers.

A few days later, Schutz showed up to the Aetna in Hartford and confronted one of the men involved in the confrontation, Leonard Collins, leading to an argument right there in the office. Collins called Schutz a “dirty pup” and Schutz reported to the Aetna President Morgan Bulkeley that he had just been insulted, to which Bulkeley asked “Why didn’t you hit him then?”

The battle that had broken out became the talk of the town. Rumors circulated that either side had threatened the other; that the Beaches were aggressive and intimidating; that Robbins was upset that the Beaches were limiting his financial support for his alleged pet projects; and that the coincidental burglaries of the church and rectory around this time were the doing of one side or the other. A neutral man said it best though: it was a shame that slander and gossip won out and that danger was on the horizon if things did not calm down.

A few days later, Robbins said he was feeling physically sick and refused to preach. William Huntington stepped in, but Robbins dismissed the parish without having the collection taken. Huntington turned on him immediately and several men stepped in again – another brawl seemed imminent. Robbins came back the next week in a special meeting and elected his own officers, deeming the ones at the annual meeting to be invalid.

This election of officers ousted William Huntington as treasurer and installed Allen Judd, setting off a massive legal battle – who was actually elected? Who actually had power here? Robbins attempted to unite the warring factions, but the fight over control over the church continued and so until that was resolved, peace was not an option.

The summer of 1914 was relatively quiet. The Beach family held off, the legal issue of who was legally treasurer snaked its way through the superior court, and Robbins kept up the lull in activity that was standard for the hot months. The factions had retained their supporters – those who sided with Robbins wanted new blood, more modern church practices, and more interest and members not seen before. Those who sided with the Beach-Huntington faction saw stability, tradition, and more certain funding and support.

However, beginning on Oct. 1, 1914, Robbins would embark on an aggressive social and religious campaign that would lead to his downfall. Since the rector job did not pay a sufficient salary to pay for him and his family (he was being paid $840 a year, half the salary needed to support them all), he was forced to look elsewhere for side jobs. He had been hired as secretary for different church organizations and for peace forums, but it was the movie theater he leased in Hartford that changed everything.

He opened the Star Theater as a way to make extra money and provide clean, more acceptable entertainment for young people on behalf of the church. He reported to the Courant that he had gotten the sign-off from the parish so that they didn’t think it would take away from his real job, but it turned out that he had probably lied about the scale and extent of his involvement (he told them that “someone” wanted to start a theater in West Hartford’s town hall and took their enthusiasm as justification for him jumping head-first into the deep end by opening a movie theater in Hartford).

Harry E. Robbins (left) at the opening of his Star Theater in Hartford, October 15, 1914.

Photo Credit: Hartford Courant (used with permission)

I’m not sure why he did this – perhaps it was a case of “ask for forgiveness, not permission,” but it caused an absolute uproar from his enemies for validating their criticisms of him and from his supporters for engaging in such a betrayal in his rush to publicize his story in the papers. The Beach family capitalized on the negative press and withdrew from all services and pulled out all their financial support. A majority of the parish began calling for his resignation, but he said that even if everyone opposed him, he would never resign until the bishop forced him out because he didn’t want to show “weakness.”

Through November 1914, he must have realized the parish was not coming back to his side (Allen Judd, who originally supported Robbins and was duking it out in court over the treasurer role against William Huntington, dropped his support and agreed to settle out of court). He lashed out at everyone against him seemingly every day in the newspaper and reporters were happy to capture his thoughts. He accused a certain family of threatening him with denial of his salary.

When it became absolutely clear that the parish looked to bring the Beach family back into power and drive him out for good, he managed to get some concessions (six months of pay and the rectory for the following spring) and agreed to resign on Nov. 29, 1914. A few months later, William Huntington came back as treasurer and Robbins moved down to the Connecticut shore, never to return. He headed north to a village in New York and took control of the church there, pushing beyond local opposition to start another theater (an eerily familiar series of events).

During World War I, he contracted the famous influenza at Camp Devens in Massachusetts while serving as chaplain there and was hospitalized at a Brooklyn, NY sanatorium until his death on Dec. 21, 1920.

The struggle for influence over St. James’s Church in 1914 was perhaps a sign of the times – a large, wealthy generational family controlling the affairs of the church they’ve supported all these years in conflict with the progressive reformer intent on bringing the church into the 20th century by barreling through the unsuspecting parish with a wrecking ball. Both sides spend several months arguing the legitimacy of basic facts, even whether or not Frances Beach was attending church regularly or whether Robbins indeed adjourned the annual meeting before he escaped.

This short period of chaos in West Hartford’s history can tell us a lot about the context of the World War I era, but it is also a terrific example of perception and nuance in historical events (and by definition, current events). Is this a story of the fledgling parish held down by the all-powerful wealthy, influential family, despite the efforts of the valiant progressive warrior to drag them into the modern era? Is Robbins just a misguided reformer who was simply unprepared for conflict with the local elders who were reacting appropriately to immediate demands for change? Or is it a case of the narcissist with tunnel vision, tearing down town after town in an endless quest to make a name for himself? The truth may lie somewhere between them all.

Google Street view of the portion of South Main Street where the original St. James’s Church was located

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.