From the West Hartford Archives: The Abandoned Highway at Tunxis Road

Audio By Carbonatix

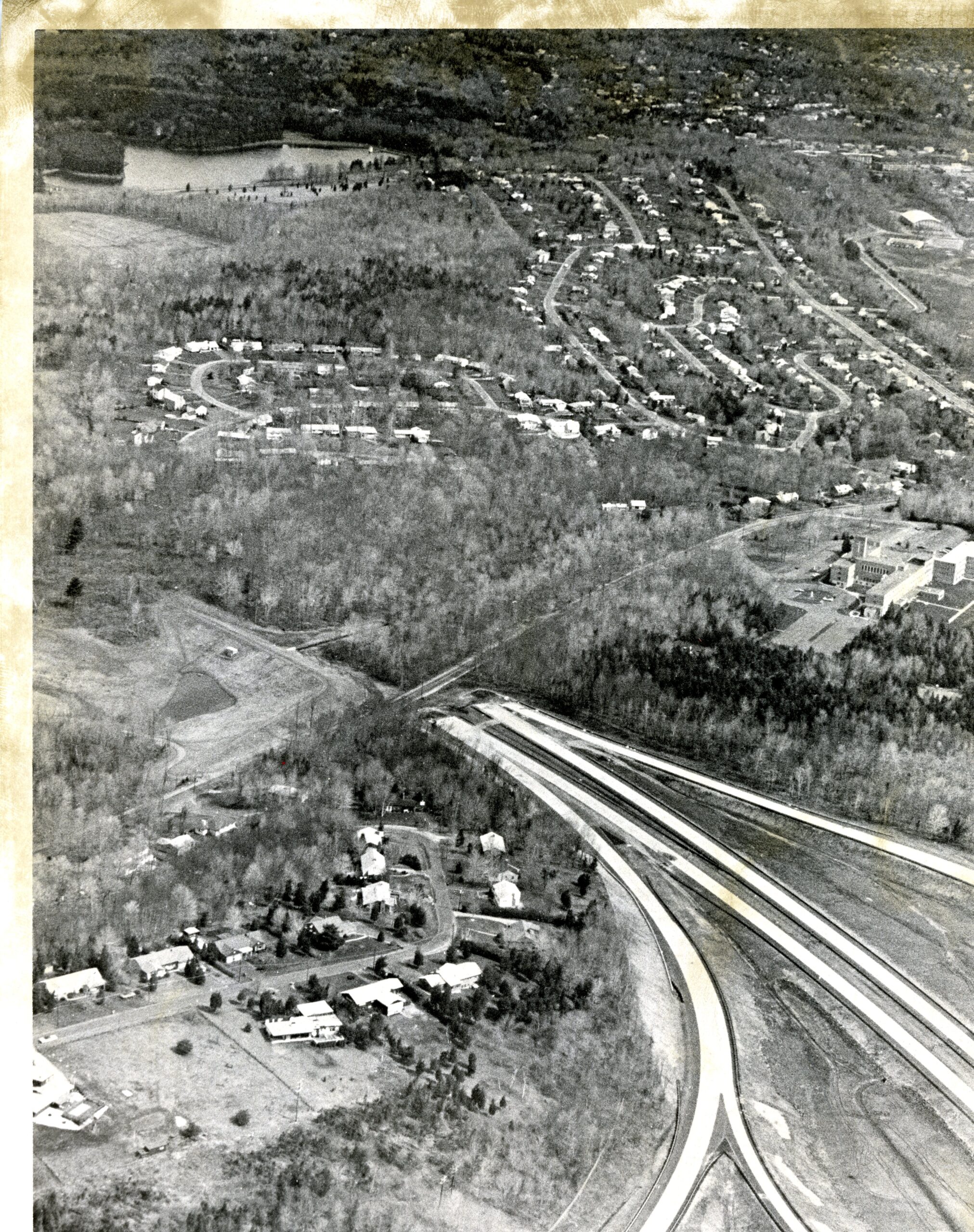

The "stack to nowhere." Visible at top left is the Farmington Avenue reservoir, and at right is the Buena Vista neighborhood and Veterans Memorial Skating Rink. Photo courtesy of the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society (we-ha.com file photo)

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

There are many prominent landmarks in this aerial photo of the west end of West Hartford and Farmington – the famous unfinished connector to I-291; the Holy Family Retreat Center monastery; the Burnt Hill Reservoir at the left; Reservoir #1; the Buena Vista suburb; and even Veteran’s Memorial Skating Rink at top right.

As someone who tends to specialize in the early 1900s in West Hartford, I figured I would look further into the post-WWII era this time.

The development of this area was centered on the post-war suburban explosion of the 1950s. The end of World War II brought a period of economic prosperity to the U.S., including Connecticut.

Increased industrial production during wartime, mainly by factories in Hartford and Elmwood, helped create a robust economy with relatively low unemployment and higher wages. The baby boom contributed to the explosion of the population. Legislation for returning veterans, like the GI Bill, made homeownership more accessible.

People were increasingly drawn to the privacy, space, and ownership of single-family homes in the suburbs. Since the 1930s, people had grown more accustomed to using personal automobiles over public transit like trains and trolleys. Cars allowed the more distant growth of streets outside of cities, like the Selden Hill neighborhood and those along Tunxis Road through to Farmington.

Americans lined up at dealerships after the war; by 1955, the U.S. produced two-thirds of the world’s automobiles. Five years later, there were nearly 70 million cars cruising along roads in the country. Car mania fueled other industries – tires, gas, and electronics – and spurred demand for consumer landmarks like diners, motels, and shopping malls.

The stage was set for the highway’s introduction to West Hartford (and most importantly Hartford). In 1956, Congress passed the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, the largest public works project in the country’s history. Interstate 91 was built along existing roads along the Connecticut River in Hartford, while Interstate 84 had to be built from square one.

Known as the “East-West Highway,” its construction remains controversial, having led to the condemnation of dozens of homes in West Hartford, the division of family farms, and significant contributions to the racial and economic segregation of Hartford by bisecting neighborhoods. Many of the effects are still felt – highways allowed wealthier white residents of the city to head to the suburbs and isolated poorer segments of the population in the north end from downtown. In 1959, anticipating incredible growth in West Hartford, plans for Route 291 were made to connect I-84 and I-91 through the Reservoir and in a loop across the north of town to Bloomfield.

The neighborhood of Birch Hill Drive, Deer Run Drive, and Royal Oak Drive was developed in the mid-1950s into the early 1960s and seemed poised to line up with the proposed highway, but the delaying of its construction by public hearings, engineering adjustments, and political shifting would line up too closely with the emergence of an activist movement affected by current events.

The burgeoning civil rights movement set a precedent for protests against government decisions that harmed communities on a number of levels. The national race riots of 1967-1968, particularly in Hartford, and college campus protests against the Vietnam War, underscored the urgency of individual actions toward justice. Most importantly for West Hartford, environmental disasters and ecological degradation led to increased public awareness about environmental threats.

Route 291 and its proximity to the Reservoir, which would arguably disrupt the ecological balance of the area, therefore became a target. In 1969, resident Charlotte Kitowski leveraged her organizing experience from her previous role on a civil rights committee to mobilize the community, including student and community groups, to form the Committee to Save the Reservoir.

Political pressure mounted against the governor and local mayors as opposition from environmentalists and concerned citizens grew and in 1973, the project was officially canceled. The following year, Kitowski was honored by the Environmental Protection Agency, which had been established under President Nixon in 1970.

This unfinished highway has almost a mythical presence today. Teenagers have held parties there for decades (or knew someone who did) under the watchful eye of local police and the outgrowth of trees and shrubbery along its roads. I have heard many names for it – the dead highway, the lost highways, the abandoned highway. It may be part of the West Hartford’s underground lore, but this stretch that ends at Tunxis Road is also a powerful monument to the colliding movements of the late 1960s.

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

As a kid I attended several protests, riding my bike along Canal Road from Westmont. It was the routing through the reservoir that did it in. They could have gone further west into Farmington through Avon to Bloomfield. When I was in High School, it was only the lack of electricity (no amps for music) that kept this place from being a full-blown party spot. Lots of motorcycle action, though! Ahhh…Good times, good times…

P.S. Glad you’re back!