From the West Hartford Archives: The End of Charter Oak Park

Audio By Carbonatix

Charter Oak Park in the 1930s. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The future of Charter Oak Park in the 1920s was bleak, but it would be another 10 years before its true end.

After a year and a half of discussion over the purchase of the park by the West Hartford Park Commission for a recreational space for residents, the push gained new life in August 1930 when foreclosure proceedings began against the owner, the Connecticut Fair Association. For years, the fairs had been far from profitable and health concerns mounted with the emergence of rats in the stables. Some events that fall continued strong, like the Grand Circuit trotting, police entertainments, and auto parades hosted by the local lodges. In the meantime, the bondholders voted to push for a sale of the property entirely.

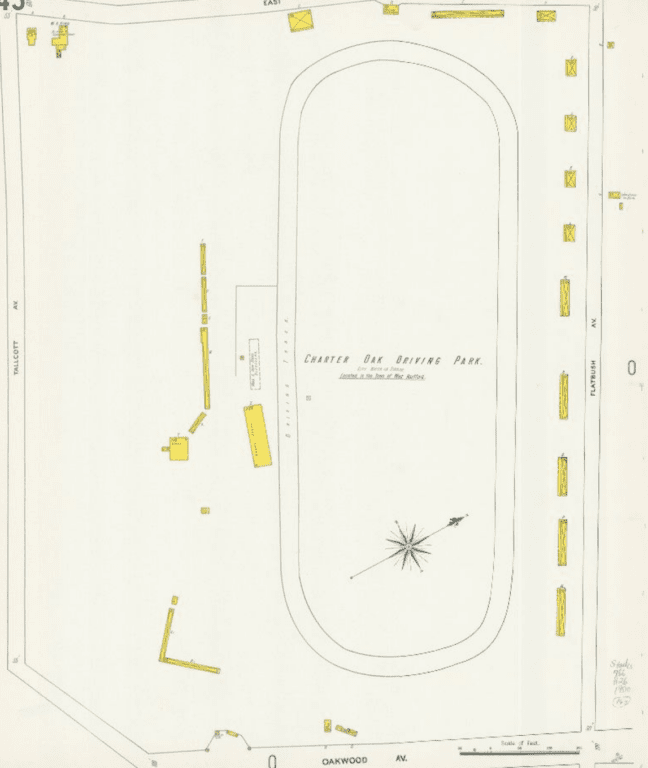

Charter Oak Park opened on Flatbush Avenue in 1873 near the corner of what would become New Park Avenue (literally the avenue to the new park).

Trotting, where horses pull a two-wheeled cart driven by a jockey, became a mainstream sport in the 1870s and involved many of the farmers and middle-class residents here. A mile-long track for harness racing cemented the use of Standardbred horses at this park. As trotting became more competitive, time records became a major part of the sport. They attracted large crowds, especially from Hartford, and fairs and festivals became common.

The 1880s and 1890s saw the rise in bicycle races. Charter Oak Park was famous enough that Thomas Edison filmed a free-for-all race on July 5, 1897 – for any curious readers, the Library of Congress has a video of the event on YouTube titled “Free-For-All Race at Charter Oak Park.” It is most likely the first video of West Hartford ever recorded.

In the 1900s, the track was used for automobile racing and even an attempted airplane liftoff. In 1909, New Britain aviators Nels Nelson and Albert Swanson spent a week running their plane, “White Wings,” on the racetrack. In the last test, they lifted the plane a foot and a half off the ground before it crashed into a fence. Nelson would have made it big after some successful flights out of town in 1911, but by then, he lost contracts to bigger manufacturers and the moment was lost. He left the industry and moved to New York to work in finance.

After Luna Park opened in 1906 at the corner of Talcott Road, crowds congregated along New Park Avenue for all of the events. In the 1910s, Charter Oak Park hosted the state fairs and Labor Day fireworks. Special constables had to be hired to crack down on trespassing and drunken men rampaging through the grounds.

Neighboring farms were carved up and subdivided for new homes, advertising proximity to the park. Gambling was rampant and fights were common. In 1919, the closing night of the Connecticut State Fair featured a riot between a gang of youths and the “razor backs,” the laborers taking down the tents and equipment of the sideshows. Police officers swung clubs at the rioters who shielded themselves with wooden boards from concession stands and put an end to the fun.

Map of Charter Oak Park in 1900, showing the grandstand, stables along the track, and outbuildings.

Charter Oak Park declined in popularity throughout the 1920s as it competed with more modern entertainments. Movie theaters in Hartford (and then the Central Theater in West Hartford Center) attracted huge audiences locally. Residents listened to music, live sports, and dramas through their radios. Cars were being used more often to travel out of town to see events, like baseball games and clubs in Hartford and beyond.

The 1920s brought a wealth of new options that drew attention away from traditional racetrack events. The implementation of anti-betting laws in the mid-1920s signaled doom for the park. Gambling had been a popular aspect of racing events and Connecticut followed the example of other states, like New York, which cracked down on the practice over concerns of corruption and immorality. With no legal avenue for betting, racetracks like Charter Oak Park struggled to draw crowds and generate revenue. And without the same prize money, horse owners, breeders, and trainers turned away from the park.

The Great Depression was the final nail in the coffin. In December 1930, the park was foreclosed and by the following spring, Chase National Bank took over the property.

Another movement began by townspeople to buy the 121-acre piece of land from Chase National Bank for a recreational park. The West Hartford finance board had to contend with organizing the growth of the town and appeasing residents who wanted a space for children to play without swiftly raising taxes. Some people wanted it to become an airfield; some wanted it to just stay a racetrack under Chase.

The 1931 Grand Circuit harness racing event continued without an issue as the town council argued over what to do. A special referendum was held on September 10, 1931 to decide whether to purchase the park – only 4% of the voters who had participated in the 1928 presidential election even bothered to vote, rejecting any purchase of the park. “Whether they represented a true cross-section of public opinion is debatable, but we may assume that they did,” wrote the Hartford Courant.

Those who rejected the plan favored the idea of little parks all over town or less financing. They got their wish in 1932 when the Beach family donated a tract of land for what would become Beachland Park, not too far from Charter Oak Park.

In the meantime, some horseracing events, soccer matches, field days, and Saturday night dancing continued there. Photographs of the trotting races in the early 1930s reflect the dying breaths of an iconic landmark. It didn’t stop people from trying to revive the energy. Democrats campaigning for Franklin Roosevelt held a rally a month before the 1932 election. Four hundred Connecticut farmers started meeting at the park by the end of 1933 to hold poultry and egg auctions. “Fancy riding cowboys” offered rodeo programs. Chicken culling contests and horse shows filled the time. A Russian Day celebration was held, with local Russians predicting soon the end of Communism in the Soviet Union (it would take another 56 years). Other communities, like Irish, Italian, and Swedish immigrants, held variety shows and picnics.

Some horsemen looked to gain control of the park and incorporate legal pari-mutuel betting in 1935. This effort was led by Ralph Gerth, the owner of Longue Vue Farm near Corbin’s Corner and noted horseman. Unfortunately for them, this did not come to fruition. “Attempts to secure the property in the past two years by bargain hunters have failed. The bankers want to get back the money they have used in financing the race track,” despite the fact that it would cost half a million dollars to build a new grandstand, stables, fences, and a track.

The death at the end of 1935 of the blacksmith and horseshoer, William King, who lived and worked across from the park at the corner of Talcott Road seemed like foreshadowing that horse racing was not coming back. The trolley company, which ran the route that stopped off at the park, began disassembling the track.

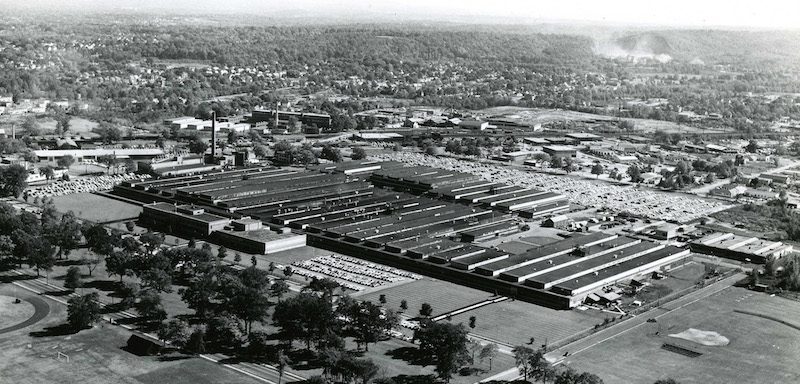

Pratt & Whitney’s West Hartford factory was built in 1939-1940 on the site of the old Charter Oak Park.

In February 1937, Pratt & Whitney, division of Niles-Bement-Pond Company, bought the former Charter Oak Park from Chase National Bank for $100,000 and planned a large factory on the property. They tore down all but three buildings (which were original to the park) almost immediately, leaving some parts of the land for use. Real estate developers capitalized on the anticipation for more manufacturing by building up houses along South Quaker Lane and Oakwood Avenue. Hartford politicians lamented the loss of industry to towns “with lower tax rates.” Over the next few years, the grandstand and track fell into disrepair.

The featured photograph is from this era. In the spring of 1939, Pratt & Whitney began construction on the site of a tool manufacturing plant, a two-story pattern storage facility, and garage and power plant. This division, not to be confused with the aircraft division, focused on heavy machinery and machine tools. A photo of the construction shows completely empty land on all four sides of the former park.

When it was finally completed in January 1940, all of the equipment from Hartford was moved to this new site. It was perfect timing – a year after World War II erupted in Europe, the U.S. government requested an addition of the factory in West Hartford for its national defense program. West Hartford’s economy would pivot by 1941 towards war production and Pratt & Whitney contributed by producing the precision gauges and machine tools needed by the Allies.

Half a century later, the vacant Pratt & Whitney Machine Tool Company factory was replaced by Home Depot and a BJ’s warehouse store after a lengthy battle. Some people in 1993 looked to bring back Charter Oak Park. Knowing the history of this area, maybe one day it’ll be back.

Home Depot and BJs in 2024. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.