From the West Hartford Archives: West Hartford High School, Memorial and Raymond Road

Audio By Carbonatix

West Hartford High School. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This is a view of the second West Hartford High School at the southwest corner of Memorial Road and Raymond Road, looking south towards the Boulevard. It is a visual reflection of one of the first challenges the town overcame in the beginning of the suburban era. It is also the beginning of Raymond Road and Memorial Road.

The first high school was located on the east side of North Main Street starting in 1865 and supplied only about one or two dozen students each year through the 1880s. Public funds were spent mainly on textbooks and musical equipment ($125 for a school’s worth of textbooks).

As residential neighborhoods opened up in town, including the east side, the town’s population grew and the need for a second (and larger) school building was felt by teachers and students alike. By the fall of 1893, the entering class at the high school was so large that there weren’t enough seats for everyone. The sophomores and freshmen had to use the same room in alternate periods – freshmen in the mornings and sophomores in the afternoon.

At the end of that school year in 1894, a report was made to discuss the crowded schools. This included not just the high school but also Elmwood and the North End schools.

When the doors opened for another year in September 1894, 50 students were entering the high school and the alternate class periods continued. A town meeting a month later discussed possible sites for a new school, with no consensus. These included a site just south of the original school on North Main Street; the Whitman land to the north, in between Loomis Drive’s outlets today; Farmington Avenue near South Main Street; and another location south of that in what is now Blue Back Square.

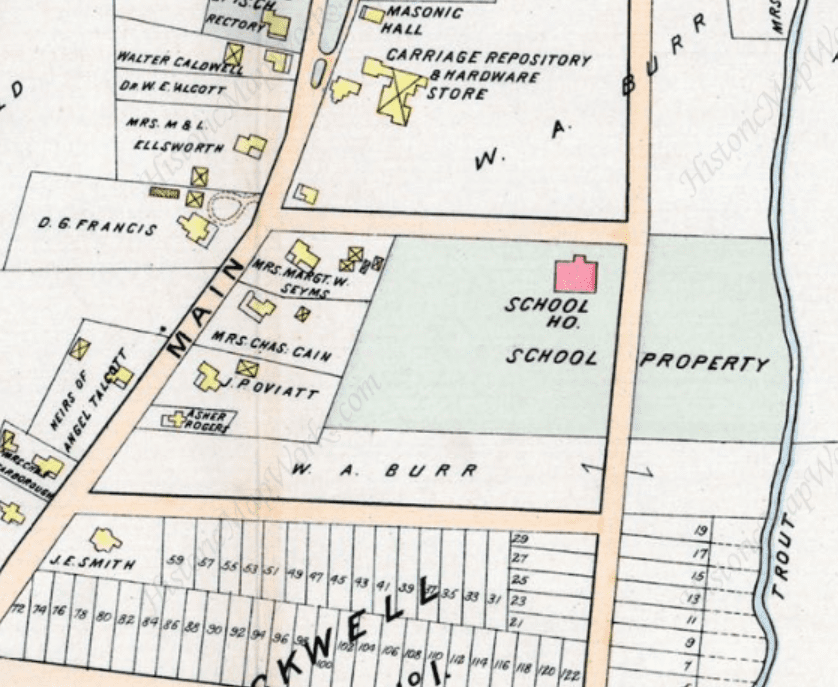

After some discussion, it was recommended in October 1894 by the school committee that the new high school be built on a 10-acre tract between Farmington Avenue, South Main Street, and Trout Brook. The site was located at what is now the southwest corner of Memorial Road and Raymond Road but at that time, neither street was laid out yet. This land was merely the backyard of George Seyms, who lived on South Main Street, where the corner with Memorial Road is. It was also the land of William Burr, who grew up in the 1840s in this section and who owned a significant part of this property. The street that was opened from South Main Street to the school was originally called Seyms Street and the street laid out south from Farmington Avenue to the school was called School Street (an original name, indeed). In a way, this school created the scaffolding for the development of this part of the Center and later Blue Back Square.

The site was not without challenge, however. Robert Price, another large landowner in town, and others filed for an injunction against the purchase of this site, claiming it was too expensive and not worth $5,000. If Price was alive today, it is easy to know what his thoughts would be that the same land (and the buildings on it) have sold for over $100,000,000!

The injunction was refused and the land was purchased by the town for the school, but the larger challenge that came a few months later in February 1895 was less financial and more existential. Within that time frame, a movement was brewing in the east side of town for the annexation of that section to Hartford. This collection of wealthier Hartford businessmen who had removed from the city and had made their homes on streets like Concord, Highland, Fern, and Prospect felt that they weren’t getting the benefits they expected and paid for with their higher taxes – sewage, water, and education. In the first months of 1895, the high school became an unexpected battleground for the two sides of the annexation fight.

John C. Webster, vice president of Aetna Insurance Company, who lived on Concord Street, led the battle and used the new high school being discussed as a sign that the town was thumbing its nose at them. Why was a new high school being discussed at all when the East Siders were dealing with a crowded school of their own, a lack of water and sewage facilities, and, in their view, a general lack of support from the town government? Webster said that the town was “feeding off the tenderloin” that paid half of the town’s taxes but got nothing in return.

Adolph Sternberg, town representative to the Legislature, argued that the East Siders hadn’t taken care of themselves in the same way that West Hartford residents had before independence in 1854. He said that they only came to town to escape from the city and did not have the same patriotism as the rest. In the newspapers, it is clear that some of it was perceived to be personal. Sternberg claimed that the only reason Webster was angry about the high school was because the site he had wanted was not chosen and that the whole annexation movement was Webster’s own pet project for revenge.

Whatever the motivations, the high school divided the town. An entire book can be written about the before, during, and after of the annexation movement, but in the end, it never got the political support it needed and the new high school was built right after it died.

A view of the school and its surroundings in 1896, including the brand new Burr Street to the south. Courtesy image

Ground was broken at the end of July 1895 and construction continued into the following year. When the new building was dedicated in June 1896, it contained seven rooms and a science laboratory, an upgrade from the cramped quarters on North Main Street.

When the school year started in the fall, the entering class of 1900 was the youngest to use the new building. Myron A. Andrews, who owned the northeast corner of North Main Street and Farmington Avenue, added to his land holdings by buying the old high school north of his house. This would become the building rented out by many different social organizations – masons, the Grange, sports clubs, and academic groups. The intermediate Center School was also moved to the new high school building, so for a period of over a decade, both schools were housed in the same building.

The principal who oversaw the transition was Alfred Howes, who served for eight years until his resignation at the end of the 1897 school year. John H. Peck then took the job as principal and was witness to many of the improvements that came later. The high school was host to many student debates; a bicycle shed was built; and a piano was bought.

More importantly, the students who passed through these halls were the leaders in the town’s development after WWI. Some of the students during these first years even became icons to the town’s history: Louise Day, whose father built many houses along the Boulevard and Raymond Road before 1900, entered the high school in 1898. After her education, she became a teacher and basketball coach at the high school, then was active in West Hartford politics. She was instrumental in the foundation of the League of Women Voters in the 1920s and was appointed as the second woman to the school board in 1938. Her advocacy for women in the political process and education in general can only be considered here briefly, but in 1950, Duffy Elementary School was named after her (Duffy being her married name). As a member of the class of 1902 (and valedictorian), maybe the better high school conditions helped nurture that active involvement in civic affairs.

Students at the entrance to the West Hartford High School in 1903. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

As the school years passed by, the surrounding area was developed. Houses were built along Raymond Road and the brand new Boulevard.

Of course, just a decade after it was built, the quarters were feeling inadequate again. In 1909, the selectmen approved the construction of a new intermediate Center School to the south of the high school along Raymond Road, which was completed by 1910. This was eventually renamed in the 1940s to the Helen Whitman School (after her death) and still stands today as the building that serves the police station.

Unfortunately, the West Hartford High School was not so lucky. After the high school moved to yet another new building on South Main Street (the old Hall High School, now the Town Hall), the old building on Raymond Road and Memorial Road was used as an elementary school (also called the Center School) and then used for municipal offices as the renamed “Rutherford Building” after building inspector Arthur Rutherford. When the offices were finally moved to the old Hall High School and soon-to-be town hall, the building was demolished in the spring of 1979 to make way for parking for the renovated Whitman School next door.

When Blue Back Square was developed in the mid-2000s, the building erected at this same corner was also given the name Rutherford Building, which can be seen on the Memorial Road side. While it doesn’t hold the same history as the old high school did, it’s a valuable reminder of the steps that led this area of the Center to be developed as it did.

When Raymond Road and Memorial Road were laid out in 1895, it became the first dividing lines that would give rise to what we have today. From the one schoolhouse on North Main Street to the sprawling complex of schools and municipal buildings in this area in the 1920s to the commercial business blocks that went up in their place, this high school building was arguably the trigger for it all.

The Rutherford Building currently occupies the corner of Memorial and Raymond roads. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

The Rutherford Building currently occupies the corner of Memorial and Raymond roads. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

I have really enjoyed your column in WeHa News. Could you do one on the Sarah Whitman Hooker House which may be the oldest standing house in West Hartford (but perhaps not for long). It is in very poor condition and in a space compromised by comercial development. I have been told that it is privately owned and I am not sure what the role or interest of the town or the Historical Comission is in that property. Can it be saved as an additional historical educational site? Are the owners interested in a collaboration to preserve this important old home?

Curious, how did students who lived further away from the Center get to school? I expect that children and young adults walked or biked much further than they are expected to do today, but what about teenagers who lived southeast of New Britian Ave, or northwest of Albany? Was the high school realistically available to those who lived in all of West Hartford’s neighborhoods? You mention a bike shed, but was that it?

Thanks, I love your columns!

Hi Liz,

One of West Hartford’s residents, Charles W. Fulton, was hired in 1896 as a school bus driver (although it was of course run by horses) and he was in charge of transporting students from across the town to the high school until his death in 1912. Most of them were living in the north end, in terms of distance, especially Prospect Ave.

In fact, his daughter Olive is in the photo of the students shared in this article from 1903. She was close enough to the Center but maybe she was able to hitch a ride!

Went to Whitman School in the early 1950s 4th, 5th, and 6th grade. But I remember entering at the very lowest level, the next level up was the fourth grade, and the auditorium, next level up was the fifth grade, next level up was the sixth grade, but the NEXT level up had a rope across the wide stairs roped off with a condemned sign! It was used for storage, and when some of us went up the explore it, the principal (Mrs. Rhodeawall) heard us all of the time, and she found some way to punish us for going there. However, three fun years!