Interim Report Looks at State, Nursing Home Industry Response to COVID

Audio By Carbonatix

Mathematica Report image

The final report from Mathematica, which has been conducting an independent review of the state’s response to COVID-19 at nursing homes and assisted living facilities, is due in September.

By Christine Stuart, CTNewsJunkie.com

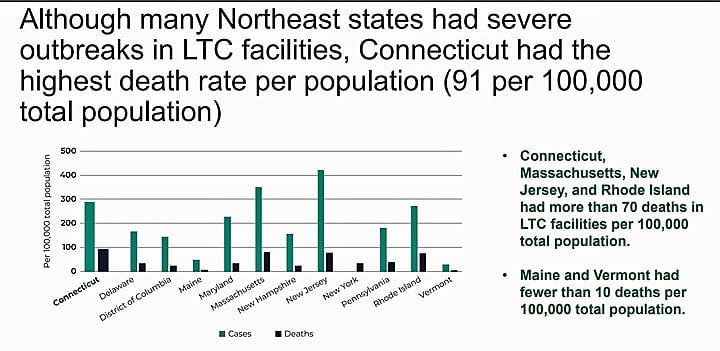

An independent review of Connecticut’s response to COVID-19 at nursing homes and assisted living facilities, where more than 3,200 people have died, found that the facilities lacked personal protective equipment and the state was slow to monitor infection control.

Connecticut has the fourth highest per-capita coronavirus death rate for nursing homes, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. However, the death toll has slowed to a trickle in recent weeks following months of testing of staff and nearly 2,000 on-site inspections of facilities.

In June, Gov. Ned Lamont hired Mathematica Policy Research, a Princeton, New Jersey-based firm, to examine Connecticut’s response and the nursing homes’ response to COVID-19.

Mathematica released its draft report Tuesday, but it will follow up with a final report next month.

“Like much of the country, Connecticut long-term care facilities were hit hard by COVID-19. Our preliminary assessment of the state’s response found that state officials made policy decisions and issued guidance based on the available knowledge at the time from national and state epidemiologists and public health experts, but that knowledge was undermined by gaps in the scientific understanding of the virus,” Patricia Rowan, researcher at Mathematica and the project’s director, said. “Connecticut took an important step in supporting this independent research, and we believe our recommendations will help ensure that the state and long-term care industry are better positioned to respond to a potential second wave of COVID-19.”

Republicans were critical of the draft report.

“I’m not sure how comprehensive the study was given some of the conclusions that we heard today,’’ House Republican Leader Themis Klarides said the briefing. “The consultant offered some pretty basic findings that seem fairly obvious.’’

The state paid $450,000 for the study.

The second part of the report is due by Sept. 30.

The interim report concluded that the highest instances of the virus and deaths were reported in nursing homes where the virus was most prevalent in surrounding towns. Large, for-profit homes and those that are part of chain organizations also had higher virus rates. The consultant also noted that nursing home patients are among the most susceptible populations when it comes to the virus.

Part of that final report will examine why the state did not cite any nursing homes for infection control-related deficiencies between March 4 and June 28.

Infection control was a major factor in being able to stop the spread of the disease inside these congregate settings. The report found that nursing homes with fewer health inspection deficiencies had fewer cases, but not fewer deaths.

Before the outbreak, 68% of Connecticut nursing homes had been cited for an infection-control deficiency at least once in the previous three years of inspections.

Interview respondents cited high turnover among infection-control staff, resulting in many positions being filled with inexperienced staff or going unfilled.

Lack of access to PPE was also a big factor in the failure to prevent the spread of the virus.

The state started distributing PPE to nursing home facilities on a weekly basis in April, and that practice continues today. However, some of the PPE being provided is below medical grade.

“Industry stakeholders reported that although the state-provided PPE comprised a small share of their total PPE, the state played a useful role as supplier of last resort,” Mathematica says in its draft report.

As with other health care settings, facilities struggled to acquire adequate supplies of appropriate PPE at the beginning of the outbreak.

The report found that nursing homes with “higher staffing ratings” had fewer COVID-19 cases.

Once the outbreak hit the state, facilities reported increased staff absences as a result of difficulties related to childcare, pre-existing conditions that placed staff at greater risk in the workplace, and fear of catching the virus or bringing it home to their families.

Facilities had to compete for direct care staff throughout the region, including in New York City, where hospitals and other settings were offering very competitive financial incentives. The report found that facilities used both financial and non-financial incentives to attract and keep staff, such as bonuses, hazard pay, and provision of meals during shifts.

In the early days of the pandemic, screening of staff focused on symptoms and travel outside the region but evolved to include temperature checks and more specific screening questions about behavior outside of work. However, facilities differed in their approach to the screening, with some asking staff to self-report symptoms and temperatures, and others dedicating staff to physically conduct this screening of all staff every day.

Communication with the state Department of Public Health improved over time, according to the report.

But the communication that facilities had with family members varied.

“Some facilities struggled to provide adequate and timely updates to family members on the status of the outbreak in the facility as well as specific updates on individual residents as needed,” according to the report.

Click here for the briefing on the report given to lawmakers.

Mathematica’s final report is due to DPH and the governor Sept. 30.

Republished with permission from CTNewsJunkie.com, all rights reserved.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.