Lamont Plants Clues to his First Budget in Opening Address

Audio By Carbonatix

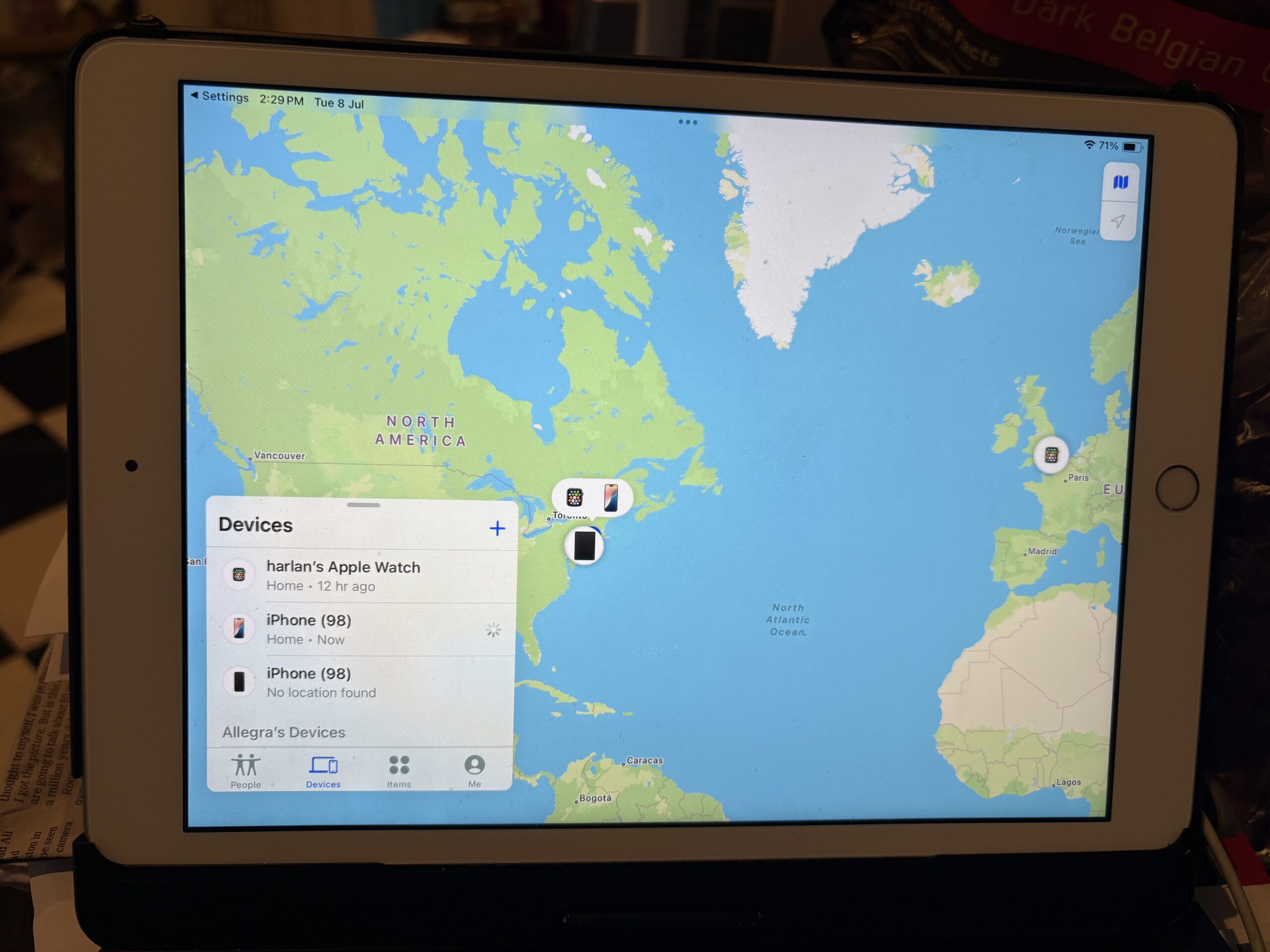

Governor Ned Lamont gives his first State of the State address. Photo credit: Ryan Caron King/WNPR (Courtesy of CTMirror.org)

Gov. Ned Lamont said he won’t play the ‘blame game’ for the state’s fiscal crisis, and will offer a budget plan that will be in balance ‘for the foreseeable future.’

By Keith M. Phaneuf, CTMirror.org

Gov. Ned Lamont’s first budget proposal isn’t due to lawmakers until mid-February. But that didn’t stop the new governor from dropping a few hints about his fiscal plans Wednesday when he addressed lawmakers for the first time.

Though full details won’t be forthcoming for weeks, Lamont indicated he would seek big savings from unionized state employees and from municipalities.

Lamont also promised a fiscal blueprint to keep state finances in the black for years to come – averting the future deficit forecasts that plagued his predecessor, Gov. Dannel P. Malloy. But given his spending priorities and repeated pledges to preserve the rainy day fund, Lamont likely will need to identify significant new revenue.

“We cannot afford to let the next four years be defined by a fiscal crisis,” Lamont told lawmakers Wednesday during his first State of the State Address. “The fate of our great state is on a knife’s edge. If we choose inaction and more of the same – we fail.”

Unions facing another big ask

Lamont’s initial challenge is to recommend a biennial budget for the 2019-20 and 2020-21 fiscal years. The legislature’s nonpartisan Office of Fiscal Analysis says state finances, unless adjusted, would run $4 billion in deficit over the two years combined.

Equally important, this projection comes despite major state tax hikes in 2011 and 2015.

Concessions from state employee unions also have been a major budget-balancing tool in recent years.

In 2011, Malloy’s first budget proposal recommended labor grant concessions worth an unprecedented $1 billion per year. Nonpartisan analysts concluded the concessions plan that was eventually ratified – including a wage freeze and new limits on health care and retirement benefits – was worth $648 million per year in budgetary savings.

Sensitive to that, Lamont said during the campaign he would call unions to the bargaining table to seek “reforms,” or “win-win” changes that would save money yet be appealing to labor and management.

Union leaders, who want a reprieve from concessions requests, are skeptical their definition of a “win-win” scenario matches Lamont’s.

Labor officials also frequently note the budget crisis stems largely from legislators and governors who served between 1939 and 2010. State officials routinely failed for decades to save for promised pension and other retirement benefits, forfeiting billions of dollars in potential investment earnings in the process and leaving current taxpayers to make up the difference.

By pledging late in last fall’s campaign not to raise income tax rates, Lamont already has ruled out labor’s preferred solution: higher taxes on the wealthy.

And on Wednesday, Lamont made it clear no one is exempt from being asked to sacrifice again.

“I refuse to invest any time in the blame game of who’s responsible for this crisis,” the governor said. “It’s real, it’s here and it’s time to confront it head on. And, please don’t tell me you’ve done your share and it’s somebody else’s turn. It’s all of our turns.”

The president of the Connecticut AFL-CIO, Salvatore Luciano, said unionized state workers carried a larger share of balancing Malloy’s first budget – dubbed “Shared Sacrifice” – than any other group in the state. “‘Shared Sacrifice’ ended up being state employees,” he said.

Luciano added, though, that he assumes Lamont’s call for sacrifice Wednesday applies to more than just labor.

“When he says everybody, he means everybody,” he said.

A push toward regionalization — and cuts to local aid?

Though Lamont never offered municipal aid absolute immunity from budget cuts, he stressed repeatedly on the campaign trail he would try to shield local governments and property taxpayers – especially those in poor cities.

But if Lamont hopes to close the deficit and invest more heavily – as he mentioned Wednesday – in job training, public colleges and universities, and education in general – local aid may have to be on the chopping block.

How might the new governor reduce the $3.2 billion in municipal grants Connecticut provides and still shield local property taxpayers?

Lawmakers have talked frequently about regionalization over the past decade, but found little agreement on how to ensure municipalities share services.

Lamont said Connecticut has to speed up this process.

“So many services and back-office functions can be delivered at a much lower cost and much more efficiently if they are operated on a shared or regional basis,” he said. “We need to break down silos and engage in the bulk purchasing of everything from health care to technology. The taxpayers of Connecticut can no longer afford to subsidize inefficiency.”

Municipal advocates have grown increasingly frustrated at talk of regionalization, arguing it has become an excuse to cut local aid in exchange for half-baked, politically safe consolidation ideas that save little or no money.

“The state has done such a poor job with data collection,” said Joe DeLong, executive director of the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities (CCM). “Let’s work with real numbers, not opinions.”

CCM unveiled a sweeping plan to bolster communities in 2017. That report, crafted by a bipartisan panel of municipal leaders, included a package of collective bargaining changes to encourage shared services.

New services provided regionally would be exempt from collective bargaining.

Mergers of existing local programs that employ unionized staff would go through a new collective bargaining effort, rather than being tied to conditions set in previous union contracts.

Lawmakers balked at these proposals and also have been reluctant to force mergers involving politically sensitive services like schools and police protection.

Can Lamont end cycle of deficits without revenue?

Also Wednesday, Lamont did more than pledge to produce a balanced budget.

He said he would offer a plan that would end the trend of future deficit forecasts.

“I will present to you a budget which is in balance not just for a year, but for the foreseeable future,” he said. “ … I want to be clear – no more funny math or budgetary gamesmanship. I come from the world of small business where the numbers have to add up at the end of the month or the lights go out.”

Throughout much of Malloy’s administration, even when the current budget was in balance, analysts warned the plan wasn’t sustainable – and that within as little as one year the state would again be spending more than it was taking in.

In fact, even if Lamont makes adjustments to avoid the $1.7 billion potential deficit next fiscal year and the $2.3 billion gap in 2020-21, the budget could spring more leaks after that – even if Connecticut and the nation don’t slip into recession.

Those surging pension and other debt costs are the chief factor, and analysts already are projecting hundreds of millions of dollars in new potential red ink in 2022 and 2023.

Further compounding matters, Lamont has an expensive campaign promise to keep: a middle-class income tax cut.

The new governor promised to dramatically expand the state income tax credit that reimburses middle-income households for a portion of the local property tax bills they face. Lamont pledged to phase in this tax break during his second and third years in office, and his campaign estimated the full cost would reach $400 million per year.

How does Lamont provide that tax cut, invest in education and job training, close an annual deficit of roughly $2 billion – and keep his campaign pledge not to raise income and sales tax rates?

“Governor Lamont has promised the state he will put forth an honestly balanced budget that will facilitate growth, put the state’s finances on a reliable and stable trajectory, and be mindful of the future while handling the struggles of the present,” Chris McClure, spokesman for the governor’s budget office, said Thursday. “ … By working with a broad coalition of experts and stakeholders across party lines, the governor and his staff will develop a budget that moves Connecticut forward through the next fiscal year and with an eye on the next decade.”

The revenue-raisers Lamont mentioned on the campaign trail – a fee on sports betting, legalizing and taxing recreational marijuana use, and tolls on larger trucks – would be a modest help toward a balanced budget.

Any toll receipts would be applied to the Special Transportation Fund, which also needs cash. But this is outside of the General Fund and would play no role in reducing that deficit.

Very preliminary estimates for revenues from sports betting have been around $40 million per year, while those for marijuana have ranged from $30 million to $166 million. In the context of an annual shortfall of about $2 billion, these are minor fixes.

Lamont has expressed a willingness to consider broadening the range of goods and services subject to the sales tax.

The state Commission on Fiscal Stability and Economic Competitiveness reported last year that roughly $600 million in new annual sales tax receipts might be raised by removing exemptions.

But that likely would involve taxing long-exempt areas such as groceries or raw materials for business – both likely to draw considerable opposition in the legislature.

House Minority Leader Themis Klarides, R-Derby, said Wednesday following Lamont’s address that the new governor will have his hands full dealing with his fellow Democrats in the legislature’s majority.

“I do believe that with his financial background he has a better understanding of where we are and how to fix” the budget, she said. “My concern is of course basically the majority party of progressive caucus members in the legislature. And so I think it’s going to be very difficult for him to do the things that he calls hard choices and hard decisions when I don’t see them doing that.”

Even if Lamont were to drop his resistance toward tapping the budget reserve, that would not help him end future budget deficits. The $1.2 billion in the rainy day fund represents a one-time source of money. And while analysts say another $900 million could be deposited after the current fiscal year ends in June, there are no guarantees beyond that.

The last state revenue forecast called for General Fund revenues to grow by just $87 million – less than one-half of 1 percent – over the next two fiscal years.

Reprinted with permission of The Connecticut Mirror. The author can be reached at [email protected].

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!