Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author Colson Whitehead Visits Kingswood Oxford

Audio By Carbonatix

Symposium students dine with Colson Whitehead. Photo credit: David Newman

Colson Whitehead visited West Hartford’s Kingswood Oxford School as part of the annual Warren Baird Symposium.

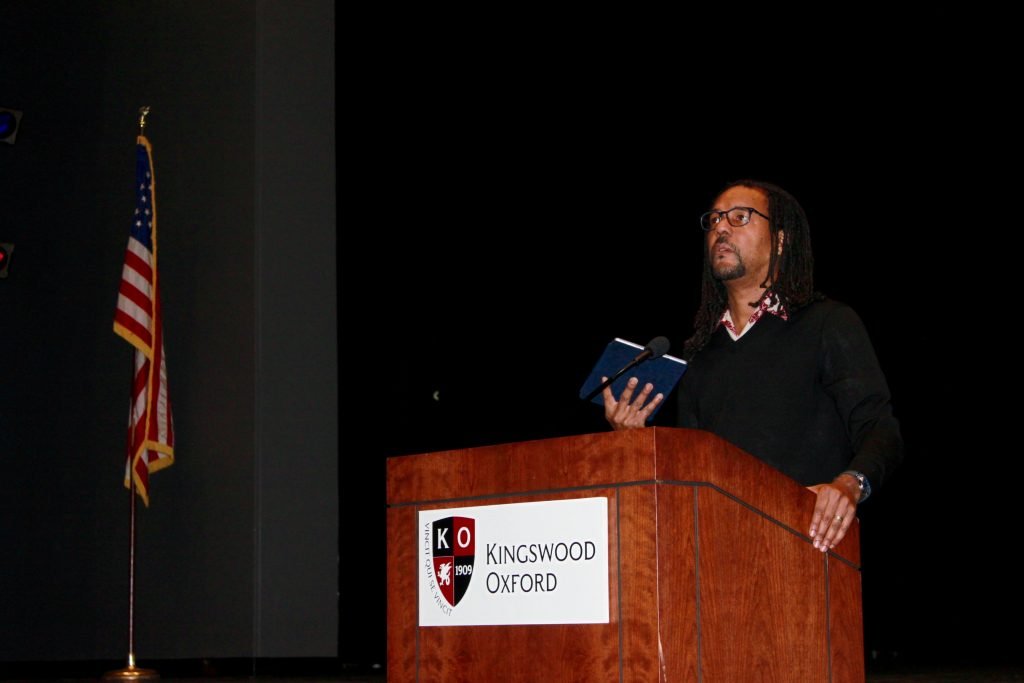

Colson Whitehead speaks at an assembly at KO. Photo credit: David Newman

Submitted by Jackie Pisani, Kingswood Oxford School

Starting from his opening line at the Kingswood Oxford assembly on Friday, Dec. 7, “I usually spend Friday mornings in my apartment weeping over my regrets so this is a nice change of pace for me anyway,” Colson Whitehead, the Pulitzer Prize winner for his immensely important work The Underground Railroad and Kingswood Oxford’s 36th Warren Baird Symposium writer, had the audience.

You knew you were in for something special. Slim, tall, and unconventionally elegant, Whitehead called to mind a hipster President Obama if the former president sported shoulder-length cornrows, a Vandyke beard, and high-end biker boots.

Deadpan and sardonic, Whitehead shared a trope about his early childhood as a poor black child, “sittin’ on the porch in Mississippi with his family, singin’ and a-dancin’.” Nothing could be further from the truth as he was raised in Manhattan, attended the prestigious private Trinity School and Harvard University.

As a child, he described himself as a voluntary shut-in and romanticized the notion of a sickly young James Joyce “forced to retreat into a world of imagination”. Rather than view illness as a burden, Whitehead envied it, and he escaped to his living room couch and watched endless loops of the Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits and read countless comic books and Stephen King novels.

By eighth grade, he found the career of a writer compelling because “You could work from home. You don’t have to wear clothes. You don’t have to talk to people, and you just make up stuff all day,” Whitehead said.

Not until Whitehead attended college, where he was introduced into the canon of highbrow writers like the magic realism of Marquez, the fantastical landscapes of Borges, and the absurdity of Becket, did he recognize how the lines were blurred between the literary authors and the beloved genre writers of his youth. While in college he considered himself a writer because he adopted an all-black uniform and an affectation for smoking cigarettes, but he admitted that he never wrote. Finally, by his junior year, he wrote two five-page stories to gain entry into the creative writing classes and was rejected. He said, “It was good training for being a writer. Everyone ignores you. No one wants to read your crap, and if you internalize it early, you can be prepared when you’re out in the world.”

Whitehead’s first job upon graduation was at the now-shuttered Village Voice, a progressive paper that boasted an editorial staff of Norman Mailer, Robert Christgau, and Jules Feiffer over the decades. After working at the paper for a few months, he approached the editor of the television section, which at the time was considered the most degrading and pedestrian aspect of the newspaper so “I thought he’d fit right in.” He penned a “think piece” on the finale of Growing Pains and Who’s the Boss which Whitehead mordantly considered the most definitive piece of writing on those sitcoms.

His first attempt at writing a novel was based on a Gary Coleman-esque child star, and the rejection slips from the publishing houses crowded his mailbox. A low point in his career, he considered various alternative careers based on his slender, feminine wrists and fingers: a pianist but realized that his back would hurt from lack of lumbar support, a career as a hand model to obtain the free watches and hand cream but recognized that the international jet set life might be too overwhelming, and lastly, the practice of a surgeon but the thought of standing on one’s feet for 10 hours a clip to perform an operation was too daunting.

While nursing his rejection he found deep insight into the bizarre lyrics of the song “McArthur Park” – “someone left the cake out in the rain” – and posited that a childhood birthday party must have gone awry, but instead recognized that the song was a profound “investigation into the artist’s journey” and served as a metaphor for his stalled career.

At that point in the assembly, Whitehead played an audio clip of the song, staring deeply and intensely into the distance of the auditorium as if the song was a divine oracle. He then chastised all the publishing houses that rejected his work by name: “Knopf and Mifflin, why did you leave my cake out in the rain?” “Houghton and Mifflin, why did you leave my cake out in the rain?” Despite Whitehead’s teasing recount of his rejection, the students absorbed an important lesson of intrepid perseverance. Nothing comes easy, and one has to work through your failures to achieve something great.

What then proceeded in his brilliantly entertaining and digressive talk, as virtuosic as any of John Coltrane’s improvisations, was his thoughts of life on other planets that may support a haiku-loving civilization centered on a 5-7-5 syllable-based structure, a Google superego app to keep you in line, the DNA of existential Neanderthals that found a way into Whitehead’s own temperament, and a musing as to why the robot R2D2 doesn’t have a proper voice box despite the extraordinary technological advances in the Star Wars universe.

The speech took an abrupt and sober turn as Whitehead read of one of the many disturbing passages in The Underground Railroad where the slave celebration on the plantation is interrupted by the arrival of the slave owners. He told the audience that the germ of the idea for The Underground Railroad came to him 19 years ago, but he felt he was not a mature and wise enough writer to make the story live on the page. He decided to write the protagonist as a woman, Cora, which examined mother-daughter relationship based on Incident in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Ann Jacobs. He found that developing any character “is always hard and if it comes too easily you’re not putting in the work in.”

An alternative history, The Underground Railroad plays with time and location, and it creates a profound narrative of the dark places in our country’s history. As an artist, Whitehead gave himself permission to take these creative liberties and chose “not to stick to the facts but to stick to the truth.” We still must all confront this vital truth, and in the words of his progressive character Landers, we can “pick each other up when we fall and we will arrive together” to a better, more hopeful future.

During Whitehead’s stay at KO, he ate dinner and taught a class with the Senior Symposium students who had read all his works and played a hand of poker as a nod to his work The Noble Hustle. He spoke at an Upper School assembly and Middle School assembly and dined and talked with KO faculty members and English teachers from other area schools.

Founded in 1983 by Warren Baird (then chair of the English department), the Baird English Symposium has welcomed some of the nation’s greatest writers, poets, and playwrights, including Arthur Miller, John Updike, Jane Smiley, William Styron, Tony Kushner, Joyce Carol Oates, Edward Albee, and others. The selected author visits campus for a reading and various student-centered events. To prepare, students in all grade levels read at least one work by the visiting writer. Students in a Senior Seminar class study the author’s work exclusively. Prior to the Symposium, they visit all other English classes and teach students about the author’s life and work.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!

Colson Whitehead listening to McArthur Park. Photo credit: David Newman

Colson Whitehead plays a hand of poker with students – a reference to ‘The Noble Hustle.’ Photo credit: David Newman

Colson Whitehead receives a student-designed t-shirt. Photo credit: David Newman