Save Our Reservoir: The Fight to Stop I-291

Audio By Carbonatix

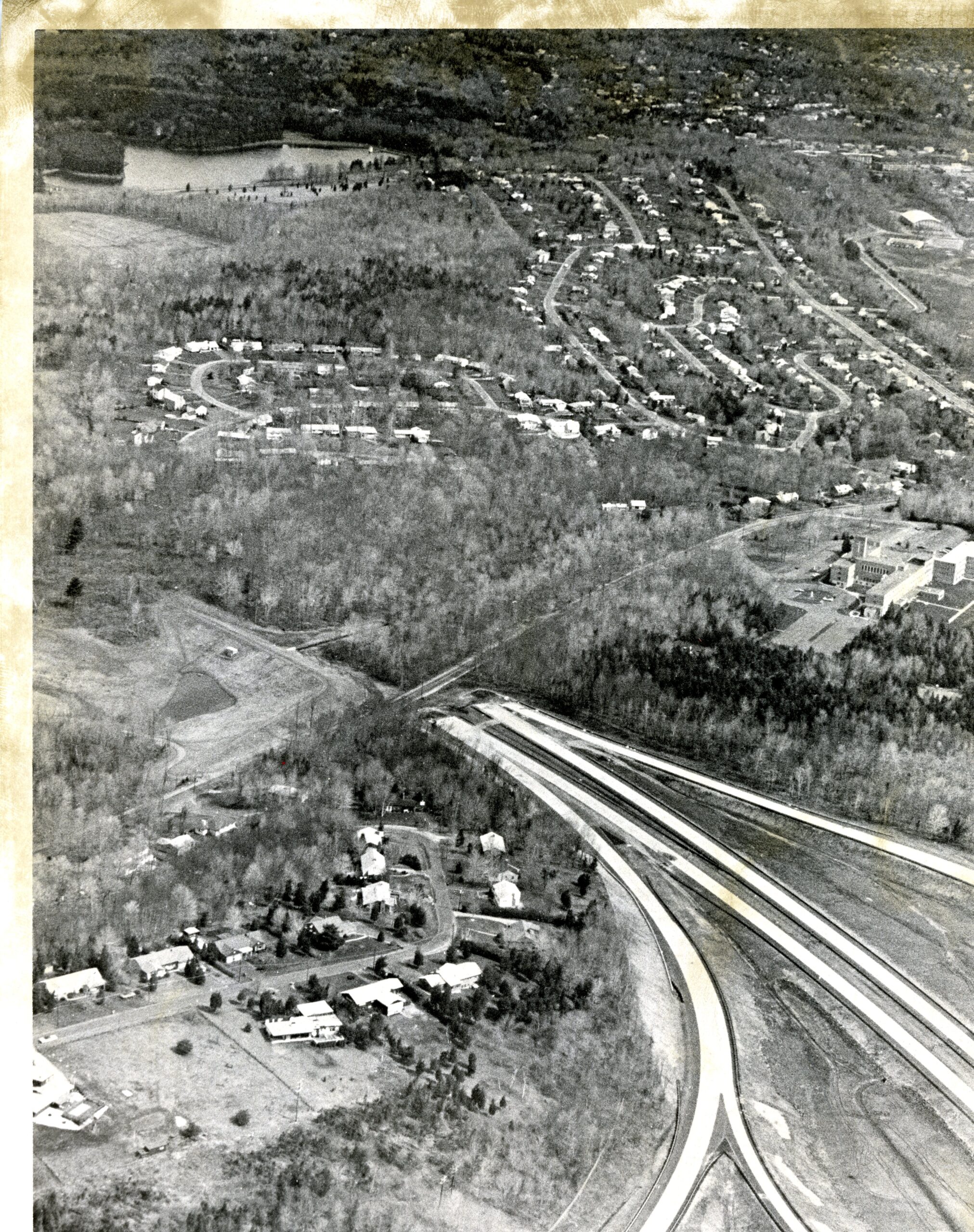

The "stack to nowhere." Visible at top left is the Farmington Avenue reservoir, and at right is the Buena Vista neighborhood and Veterans Memorial Skating Rink. Photo courtesy of the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society (we-ha.com file photo)

West Hartford Historian Tracey Wilson first wrote this article in 2018. It was revised in 2024 and submitted for publication to We-Ha.com.

By Tracey Wilson

Have you ever noticed the four-level stack of highway exits and entrances on I-84 near Westfarms Mall that leads to nowhere? The federal and state governments built this stack, between 1969 and 1973, to connect a 27-mile highway planned to encircle the city of Hartford. Today, the stack stands as a testament to a project abandoned after a prolonged battle – a symbol of both a missed opportunity for traffic flow and a hard-won victory for environmental and community activists.

The story of I-291 is deeply entwined with post-World War II America’s push for highway expansion. In 1956, the federal government, under the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, embarked on an ambitious plan to build highways to ease congestion through and around cities. Hartford, Connecticut was no exception. Plans for I-91 and I-84 came to fruition by the early 1960s. Plans for I-291 envisioned a circular highway to avoid Hartford traffic that would connect Rocky Hill, West Hartford, and Bloomfield, continuing east through East Hartford before closing the loop back at Rocky Hill.

From the beginning, these highway plans faced opposition. Public hearings, a requirement of the 1956 Act, gave local citizens a voice in the process. This set the stage for a 15-year battle that forced the state and federal governments to ultimately abandon the western section of the highway – thanks in large part to the efforts of one woman: Charlotte Kitowski.

The story is also a window into a historical site in West Hartford that historians tried to use to stop the building of the beltway.

The Birth of a Highway and Early Opposition

In 1957, planning for I-291 began in earnest, with a particular focus on West Hartford and Bloomfield. The proposed highway would connect with the planned I-84 and I-91 highways, facilitating the anticipated suburban boom. Demographers projected that West Hartford’s population would surge from 60,000 to 100,000 people by 2000, and the area’s commuters would need quick access to major routes. The 1957 opening of Connecticut General Insurance Company’s Bloomfield campus further accelerated these plans, with an interchange slated to spill out near the new insurance offices.

However, these plans weren’t universally embraced. At a series of citizen meetings from 1960 to 1966 in Farmington, West Hartford and Bloomfield residents voiced their concerns.* At a 1960 hearing at Duffy School, more than 200 West Hartford and Farmington residents wondered if there was even a need for this highway. Citizens were outraged at the idea of homes being demolished, particularly in the Oakland Gardens section of Farmington.

Two months later, the State Highway Commissioner got approval from the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads to take down 155 houses by eminent domain for the highway. The highway would enter the MDC Reservoir No. 1 just to the west of the new filter beds installed to guarantee clean water. It would pass directly through Reservoir No. 3, which would be drained and the road built on the reservoir bed. It would proceed to the west of Reservoir No. 2, go across Albany Avenue with access ramps planned at Albany Avenue. It would pass through a wooded area east of Reservoir No. 6. (HC 8/2/1960) The road would continue to Simsbury Road and Main Street where it would meet Cottage Grove Road, another section of Route 291.

As more homeowners protested, legislators, with the support of the Metropolitan District Commission, an agency charged with protecting a large segment Connecticut’s drinking water system, actually suggested rerouting more of the highway through the Reservoir to avoid taking down houses in Farmington. By 1966, following protests from Farmington residents, the state shifted the route to pass directly through the reservoir and avoid demolishing 47 houses. The MDC tentatively approved the plan in August 1966 with a timetable for completion in 1974.

This decision galvanized environmentalists who saw the reservoir as a precious water and recreational resource.

By 1969, activists were emboldened to protest the path of the highway through the MDC Reservoir system.

This increasing national interest in environmental issues was spurred by the January 1969 blowout of an offshore oil drilling rig in southern California which released more than four million gallons of crude oil into the Pacific Ocean and onto the shores at Santa Barbara. Wildlife was decimated, and scientists were not prepared for this environmental disaster. Could something like this happen with a four lane highway next to a reservoir?

MDC reservoir, Farmington Avenue. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

Enter Charlotte Kitowski

Charlotte Kitowski (1923-2005), a nurse, activist, and longtime West Hartford resident, emerged as the face of the movement to stop I-291. By 1969, she had already made a name for herself through her work with the League of Women Voters and her vocal opposition to the House Un-American Activities Committee during the Cold War. She expressed her ideals around community engagement like this: “People say there’s nothing you can do. I’ve just never had that feeling. … Challenging the government is the way the government works!”

Kitowski’s leadership was pivotal. Her efforts to protect the reservoirs from the highway cemented her legacy as an environmental advocate.

Kitowski wasn’t alone. High school students drafted petitions, and with her guidance, the community came together to form the Committee to Save the Reservoir (CSR). Their first major event, the “Reservoir Ramble” on May 25, 1969, (a little less than a year before the first Earth Day) drew 140 attendees, sparking media coverage and inspiring more activism. Within days, the CSR had collected 6,700 signatures on a petition to stop the highway. By the time they delivered it to Governor John Dempsey, they had 10,000 signatures.

An April 1969 resolution brought by Republican West Hartford Mayor Ellsworth Grant deplored putting the I-291 highway through the Talcott Mountain reservoir, saying that it would lead to the devastation of open space and endanger the water supply. In September 1969, Bloomfield’s Mayor Lew Rome, also a Republican, came to a West Hartford Town Council Meeting, all supporting the highway. Six of those seven did not run in November, the Democrats took control and officially opposed the highway.

Mobilization and Legal Battles

The CSR’s growing momentum led to a public hearing on September 25, 1969, attended by over 1,100 people. Held at Hall High School, the hearing featured testimony from Connecticut’s Health Commissioner Dr. Franklin Foote, who warned that lead and chlorine contamination from the highway’s proximity to the reservoirs could poison the water supply. A biochemistry expert from Washington, D.C. and a professor from Dartmouth School of Medicine both spoke against the highway stating health risks to the water supply.

The state Department of Transportation (DOT) dismissed the warnings, insisting the route was necessary for regional development.

CSR retained lawyers who filed suit against DOT stating it ignored Section 4 (F) of the 1966 Dept of Transportation Act which required DOT to say that there were no feasible and prudent alternatives to the use of parklands. The suit claimed that DOT did not look at alternatives, such as mass transit, to the interstate highway.

On the first Earth Day, in April 1970, Kitowski and CSR organized a bus tour through West Hartford to galvanize support; more than half of those on the tour were under 18. The buses, donated by the Connecticut Co., took riders on an ecological tour of town including where the state planned to build I-291.

In 1970, Kitowski and the CSR intensified their efforts, reaching out to the U.S. Department of Transportation. Their persistence paid off. On Oct. 15, 1970, the federal government suspended the design of the Bloomfield section of I-291, citing environmental concerns.

The Fight Reaches the Federal Level

At this point, Kitowski felt the best path to stop the highway was to bypass Connecticut DOT and go straight to the federal government. She urged people to write to Secretary John Volpe at the Department of Transportation. At the same time, CSR continued its letter writing campaign and petitions to state, local and MDC officials.

With the federal government involved, the battle shifted to Washington, D.C. CSR members traveled to the capital to present their case to the Department of the Interior. Their 300-page report, detailing the environmental risks of the proposed highway, impressed officials who had previously been unaware of the scope of opposition. In response, the Interior Department demanded a new environmental review and ordered the state to hold another public hearing.

By 1971, the movement against I-291 had gained national attention. The newly established Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), led by Secretary William Ruckelshaus, officially opposed the highway. Governor Thomas Meskill, facing increasing pressure, publicly promised to keep the highway out of the reservoir, a promise the CSR ensured he wouldn’t forget. In September 1971, 500 cyclists staged a “bike strike” at the reservoir, protesting the highway and calling for its cancellation.

The Final Victory

The final blow to I-291 came in August 1973, when Governor Meskill officially killed the project, just days after his pro-highway transportation commissioner resigned. Part of the deal included a change in the federal government reimbursement policy, allowing Connecticut to redirect the I-291 highway funds to other projects. This provided a political and financial safety ramp for the governor and marked the end of the I-291 project.

In 1974, the EPA awarded its Environmental Achievement Award to Charlotte Kitkowski for her leadership. The regional EPA administrator praised her for proving that “responsible public participation can be the keystone of our environmental efforts.”

Legacy and Historical Preservation

Though the battle to stop I-291 ended in 1973, the fight had a lasting impact. Its historical impact continues as the highway was to pass right next to a historical site near Reservoir 6, a Revolutionary War Camp.

In 1967, the State Highway Department planned to develop about 30 acres east of Reservoir 6 into a state park to celebrate the Revolutionary War Camp and hospital Camp, used between 1775 and 1779. A Hartford Courant article detailed the support of the State Park in part, to encourage residents to support the highway. The Highway Beautification Act would pay 100% of the cost of this park which would include information booths, roadways, parking areas and shelters. According to this plan, the I-291 highway would run about 100 feet from Reservoir 6 and then about 400 feet from the Revolutionary War Camp. Highway officials said they had been considering making this area into protected open space since 1960.

In the late 1960s, historian Nelson Burr began researching the Revolutionary War camp located near Reservoir 6. The camp was inhabited with about 200 tents for about a week in 1778 as Israel Putnam’s 800 troops made their way to Danbury to protect Connecticut from a British incursion. It then was used as a hospital with supplies provided by at least 68 families in West Hartford.

The I-291 activists realized how close the proposed highway route was to this historically significant site and used it to fight the highway. Historians hired an archaeologist to study the site in 1973 and 1974. Local citizens successfully had the Camp added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. This protection made it even more difficult to develop this area, especially with a highway.

This action also happened right around the Bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence. And while historians wanted people to know the story of this camp, they feared that the site would be ransacked and ruined. Fifty years ago, the citizens decided to use this historical information to help stop the highway, but did not want the story told to a bigger audience.

As the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence approaches, historians and community members are once again looking to tell the story of this Revolutionary War camp, as well as the broader story of West Hartford’s fight to preserve its reservoirs – a fight that brought together environmentalists, walkers, runners and bikers, students, and everyday citizens to protect their community’s future.

Plans are in the works to tell the story of the camp as well as other events, including the history of slavery on the site, the strike of Italians building the Reservoir in the 1890s, and the activism around I-291. This can be a legacy left by West Hartford250 for the next generations.

As a biker, advocate and historian, one of my favorite anecdotes involved Kitowski and her bike in September 1971. DOT Commissioner Wood criticized Kitowski for driving her car on Interstate I-84 to get to a meeting at his office. He insinuated that we all need these highways, even Kitowski! At the next meeting, Kitowski rode her bike, and carried it right into Wood’s office, proclaiming there were no provisions for locking it up outside. The Hartford Courant documented her commute with two photos in the morning paper, symbolizing the spirit of the entire campaign.

Listen to the podcast “The Stacks to Nowhere” on Trout Brook Tales at https://www.podomatic.com/podcasts/chuck85898/episodes/2024-12-06T12_07_06-08_00.

*In February 1960, the studied route was planned to “swing south through the Metropolitan District Commission land to meet the East-West Highway (I84) west of Corbin’s Corner in Farmington.”(HC 2/21/1960) By February, the MDC willingly retained the highway and allowed for it to avoid Batterson Park in Farmington. By March, Farmington officials tried to get the route pushed further east to avoid taking residences. (HC 3/3/1960) The hope was that the state would purchase the land needed and start construction in 1963.

MDC Farmington Avenue reservoir. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Charlotte’s true legacy is the countless hours lost and gas wasted by those forced to sit in the traffic she caused.

As a fairly new resident to West Hartford and someone enamored with the reservoirs, I found this story engrossing and enlightening. As we begin to own the ways highways have divided and punished some of our city neighborhoods to the point where we are now looking to remove interstates and reconnect those neighborhoods, it is impossible not to be in awe of Charlotte Kitowski. And maybe, just maybe, we could learn a lesson in humility from all this and take our time with our own development projects, especially where the environment and less affluent communities are going to pay an inordinate price. It probably took Charlotte a little longer to bicycle rather than drive to that 1971 meeting, but, really, what are we rushing to?

Well said Ed.