West Hartford Doctor Uses Disaster Skills to Create COVID-19 Plan at UConn Health Center

Audio By Carbonatix

Dr. Rob Fuller stands in front of the COVID-19 Patient Evaluation tent he created as part of John Dempsey hospital's response plan. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Dr. Rob Fuller has created a COVID-19 response plan for UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital’s Emergency Department, using the skills he has acquired responding to disasters throughout the world.

Ambulances park outside the COVID-19 Patient Evaluation area, a tent in the parking lot outside the emergency department at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

By Ronni Newton

Dr. Rob Fuller is used to danger and crisis, and he’s one of those people who runs toward it, ready to pitch in and help by using not only his medical skills but also his mechanical skills and old-fashioned ingenuity.

Never before has the danger been right in his backyard, surrounding everyone in the region, the state, the country, the world.

“It’s certainly a bizarre world in emergency medicine,” he said of COVID-19.

Those who arrive at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital with symptoms of COVID-19 will enter through the Patient Evaluation area, a tent in the parking lot outside the emergency department that leads to a separate entrance to the hospital. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Fuller, a West Hartford resident who is the head of Emergency Medicine at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital in Farmington, has been planning, mobilizing resources and people – even his own family members – and over the past week has essentially turned UConn into two separate hospitals, with two separate emergency entrances, to protect patients and staff and to prepare for what he expects will be an onslaught of patients.

The critical considerations are “space, staff, and stuff,” Fuller said.

“If hospitals are doing it right, they’re looking for ways to expand their patient space,” said Fuller, who is not only helping UConn ramp up for the pandemic but also consulting with other hospitals in the state. Most are following plans similar to what he is doing at UConn.

“Every hospital in the state is working to identify additional beds,” Dr. Matthew Cartter, the state’s epidemiologist, said in a briefing Wednesday afternoon.

Hospitals are canceling elective surgery, opening up closed wings, and building mobile field hospitals like the one that opened in a parking lot at Saint Francis Hospital on Tuesday.

Staffing is also critical, said Fuller, and it may be necessary to double the inpatient operations, but that’s not an easy task for many reasons.

“This is a situation where the staff may be imperiled themselves,” he said. Because the staff themselves can get sick – and it has already happened in Connecticut, where the first few announced cases were among employees at Danbury, Bridgeport, and Norwalk hospitals – staffing can be particularly difficult.

Fuller said there are people that will stand up to the challenge, those who will run away because they don’t have the temperament to handle it, and those who try but get sick or work themselves into such a deep exhaustion they can no longer function.

“Building a staff with the conditions is pretty tricky,” said Fuller, especially when people aren’t used to having to respond to something like COVID-19. Personally, he said he would prefer to advance young people, residents, or even fourth year medical students, getting them involved in the process. They may be up on modern treatments, and less likely to have serious problems if they do get sick.

Equipment, including a ventilator, is awaiting COVID-19 patients at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

As for the “stuff,” Fuller said he’s also focused on making sure the hospital has enough ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE) like N95 and regular masks.

Because of his expertise in dealing with the aftermath of disasters – working with teams from the International Medical Corps (IMC), Fuller has responded to nearly a dozen emergencies throughout the world like 9-11, the tsunami in Indonesia in 2002, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and Hurricane Dorian in the Bahamas just last fall – he’s already had unimaginable experiences and isn’t afraid to just jump in and do what needs to be done.

“I’m good with tents, so I immediately arranged for a tent,” Fuller said. The large, heated structure that now sits in the parking lot outside the John Dempsey Hospital Emergency Department was built by Fuller, his wife, his daughters, UConn staff, and other volunteers.

Having the tent allows for two separate streams of patient care. There will still be the regular emergencies – broken bones, strokes, heart attacks. “Those people deserve to be cared for in a place without infected people,” Fuller said, and when they arrive at UConn they go through the regular entrance.

Pathway for those who are ambulatory that leads to the COVID-19 Patient Evaluation area. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

“You need two emergency departments suddenly, and then you need two hospitals suddenly,” he said.

As patients approach the emergency department there are directional signs, so those with a fever or other symptoms head for the COVID-19 evaluation area. Arriving ambulances are also steered in the right direction.

After it was completed over the weekend, UConn’s tent was inspected by the state’s Department of Public Health. “They gave their blessing for us to start using it.”

Hospital staff has been practicing, but the tent and accompanying patient evaluation system wasn’t needed on Monday or Tuesday, so Fuller was able to provide a tour.

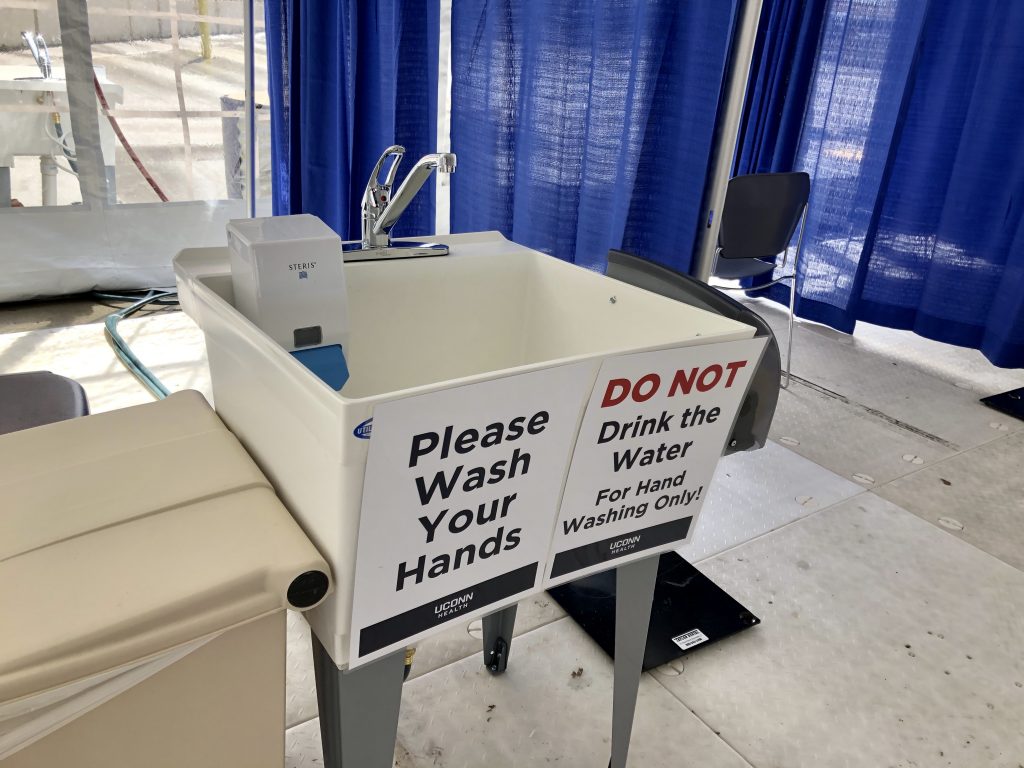

He pointed out the walkway – to be used by those patients who are ambulatory – that leads from the regular emergency entrance to the tent. It’s lined with reminders about hand washing and other precautions.

There’s a sink outside, and one inside as well, with a touch-less trash can for paper towels.

Inside the tent are separate areas where nurses initially speak with patients to get basic information. When the chairs face the wall, they’re clean, Fuller said. When the patient sits down, the chair is turned toward the center of the tent.

Nurses or doctors will clean the chairs themselves after each use, to prevent the housekeeping staff from having additional exposure – and the need to use up valuable PPE. The doctors and nurses will also be responsible for emptying the trash into a receptacle that’s outside the tent.

Entrance into the COVID-19 section of the John Dempsey Hospital emergency department. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

No treatment will take place inside the patient evaluation tent, but nurses and doctors will triage patients into three categories. Those who are “mildly ill” will be sent home to quarantine themselves.

Those with a “medium” level of illness will be rolled in through the western part of the emergency department, through the entrance that was already labeled “Decon/Ante Room.”

“We’ll evaluate them, see if we can get them stable and able to go home,” Fuller said.

Those patients who are “very, very ill,” including those who arrive in critical condition by ambulance, will also enter through the western part of the emergency department through the decontamination area and be admitted to the hospital and will be housed in an isolation area. Those critically ill patients are the ones who may need to be intubated.

A space inside the COVID-19 area of the UConn John Dempsey Hospital emergency department where patients can be evaluated and treated. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

The flow “keeps all the COVID-10 patients away from other people. They are all clustered,” Fuller said.

Some possible COVID-19 patients have arrived at John Dempsey Hospital already, but the flow has not been so great that the tent has had to be put to use – yet.

“This is the ‘lull before the storm,'” Fuller said. People have been hunkering down in their homes, and statewide the hospital census has seen a decline due to the lack of elective surgery as a means to make more beds available.

“I expect that within a week we’ll be using it non-stop,” said Fuller.

Data released by the state indicated that as of March 25 at 4 p.m., 113 patients have been hospitalized in Connecticut as a result of COVID-19. That’s a jump of 42 from the previous day. In Hartford County, there were 24 patients hospitalized as of March 25.

Fuller knows how to work in an austere medical environment, where there may not be a building with walls, or running water, or reliable electricity. But few people, he said, are really prepared for dealing with something like the COVID-19 crisis – especially when it’s everywhere.

Fuller has been in situations where there have been infectious diseases, including a measles outbreak following the tsunami in Indonesia. There have been tetanus outbreaks, but that’s not contagious. He left Haiti before cholera became an epidemic, but he has worked in places like the Dominican Republic where cholera, which is contagious, is endemic.

“There have been little smatterings, but [a highly contagious virus] was not the main course,” said Fuller.

“This isn’t on the ebola contagion scale,” Fuller said of COVID-19, but it’s really “the canary in the coal mine” for emergency departments that are on the front line facing the the coronavirus in the U.S.

“This will be the REAL thing – in capitals. The first time anyone in living history will face this tidal wave of patients,” Fuller said. “It’s the first time on my own turf that we’re being clobbered by a disease,” he aded.

“We’re having trouble as a society switching gears,” he said. When he’s responded to disasters elsewhere in the world, the regular rules have already been abandoned.

“The gears are already stripped. The monopoly board has been shaken clean,” he said.

Even having to wait for a Health Department inspection before using the tent is weird to Fuller, and while in this case it’s not impeding the response, in general he said you can’t follow a rulebook when there’s a disaster.

“You have to cast away the top-down [rules] … You need bottom-up enthusiasm.”

As an example, he said, if a nurses are working long hours and there’s a lull, let them sleep. It’s not what they usually are permitted to do, or what the union contract might specify, but there’s no room for rigidity in an emergency situation.

“I just do it,” Fuller said, laughing. “Then I will beg for forgiveness.”

Dr. Rob Fuller washes his hands before entering the COVID-19 Patient Evaluation tent. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Other than the fact that there are more rules to follow in the U.S. than in other countries where he has done disaster response, Fuller said it’s also difficult to change modes, to go home at the end of the day to his regular life.

“When you go to a disaster you are fully out of your normal life, you are totally immersed in it,” he said. You live, breathe, eat, and sleep the situation.

“Here I go to work and get into disaster mode,” he said, but then he goes home and is a dad and a husband. Last Friday was “match day” for medical students, and he and his family celebrated when his daughter’s longtime boyfriend got his residency match.

When asked to share some other good news, Fuller mentioned the dinner he was planning to eat that night, followed by watching “The Princess Bride” with his family.

Then he seriously added, “I hope the epidemiologist’s projections are wrong by a factor of 10.”

He’s been immersed in the science and the prediction models published by the Imperial College. Even looking at the middle number – neither the worst- nor the best-case scenarios, “We’re just stewed,” he said. He said the epidemiological projections seem right on track.

But time will tell, he said, and like a weather forecast, locally the closer we get to the last week of March, the more reliable the data will be.

He’s also agrees with the advice of Dr. Atul Gawande, a Massachusetts surgeon who is also a writer for the New Yorker. Gawande’s recent piece, “Keeping the Coronavirus from Infecting Healthcare Workers,” provides guidance for keeping hospitals functional and staffed amid the COVID-19 crisis based on some of the successful experiences in Hong Kong and Singapore.

Chairs where patients will be evaluated in the tent face outward so when they have been cleaned – and that’s done by doctors or nurses to keep down the number of people who must enter the tent. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Procedures from the “public health playbook,” Gawande writes, have helped flatten the curve in those countries and bring some hope. “One is that this coronavirus, even though it appears to be more contagious than the flu, can still be managed by the standard public-health playbook: social distancing, basic hand hygiene and cleaning, targeted isolation and quarantine of the ill and those with high-risk exposure, a surge in health-care capacity (supplies, testing, personnel, wards), and coördinated, unified public communications with clear, transparent, up-to-date guidelines and data. … Those of us who must go out into the world and have contact with people don’t have to panic if we find out that someone with the coronavirus has been in the same room or stood closer than we wanted for a moment. Transmission seems to occur primarily through sustained exposure in the absence of basic protection or through the lack of hand hygiene after contact with secretions.”

“People are hyper-fixated on gear they don’t need to use,” said Fuller. They are burning through it faster than necessary, and he that in many cases a regular mask, if worn by medical personnel and the patient, in combination with careful hand washing and distancing, will be effective, as they were in Hong Kong where no healthcare workers became infected.

“I could be called silly and wrong,” Fuller said regarding his approach, but he’s doesn’t feel like he’s making an error in judgement.

When the crisis passes, people could say, “You built this big tent and we didn’t need it.” He’s fine with that.

“In gaming theory you decide how you want to lose. If I’m wrong then we have set up more tents than anybody,” he said. But if he’s right, and there’s an onslaught of patients who need care, then they will be as prepared as possible.

“None of us have lived with an epidemic like this in our backyard.”

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!

Hand washing stations are located outside and inside the COVID-19 Patient Evaluation tent. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Those who arrive at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital with symptoms of COVID-19 will enter through the Patient Evaluation area, a tent in the parking lot outside the emergency department. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Those who arrive at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital with symptoms of COVID-19 will enter through the Patient Evaluation area, a tent in the parking lot outside the emergency department. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

COVID-19 patients are segregated at John Dempsey Hospital. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

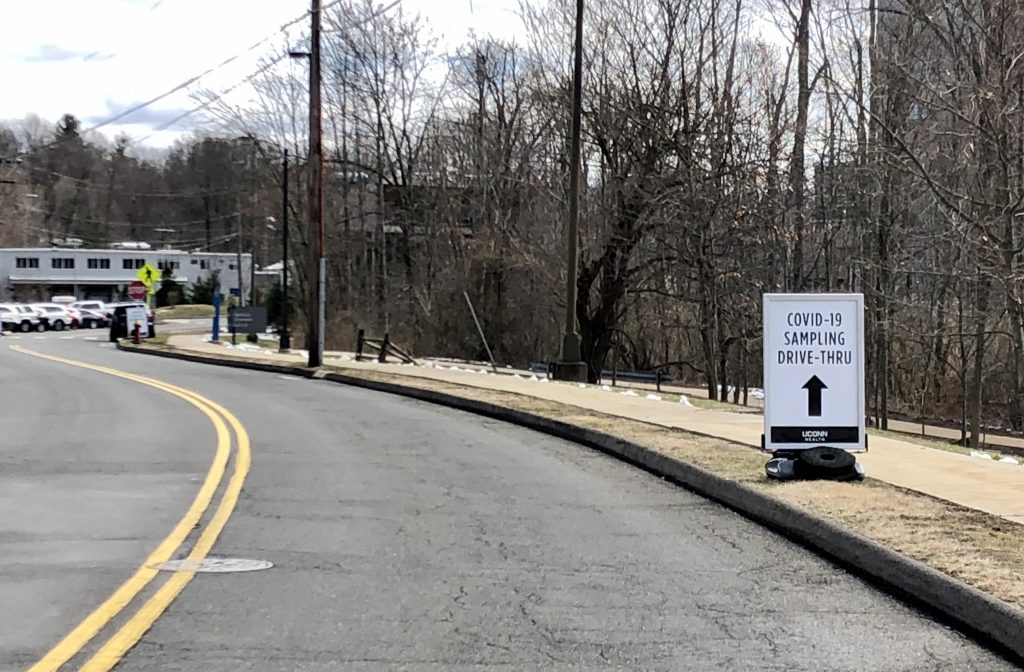

Separate from the emergency department, there is also a drive-thru testing facility at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Separate from the emergency department, there is also a drive-thru testing facility at UConn’s John Dempsey Hospital. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Thanks so much! Our son, Edward, (a professor @ Rowan U., first alerted me and his younger sister to this site a few weeks ago, and I look for it almost daily now that our daughter, her husband, and their 3 children now live in Southington and I with them after our 6 years in Frisco, TX. When we returned from TX, they found this house in a central community and added to it for accommodations for me, and it’s as nice as can be except that it’s not in West Hartford, as far as I am concerned. Ann and David and the 2 boys lived in Madison, with Ann commuting to Hartford; their youngest, a girl now 12, was born in TX.

My gosh – Hello Ann Kazarian –

My name is Jay Marcinowski from Edinboro, Pennsylvania and I truly hope you are doing well given 3 years have passed since your post. I have been searching for you for a while, and found your comment online purely by accident. To introduce myself – I am a member of the Edinboro Area Historical Society and contribute historical articles and research to support the organization. In short we are currently putting together an article about the ‘undertakers’ of Edinboro: of which your grandfather, Almon W.(Lillian) Herrick, was a furniture dealer and one of several undertakers in our town. He worked between (about) 1905 into the mid 1930s. A diligent search has revealed many, many articles, mentions, and advertising but….I have NO photographs of your grandfather. Thus, it was essential to find a descendent in hopes of a family photo. I hope I am talking to the right person. My email is [email protected]. Ph: 814-734-7657 I sure hope to hear from you. please respond if you would.

All the best

Jay

[…] of the most high-impact stories I did last week was an interview with Dr. Rob Fuller at UConn Health Center, which included a tour of the COVID-19 Patient Evaluation facility he planned and constructed with […]