College Bound: Getting Your Best Grades Ever!

Audio By Carbonatix

Adrienne Leinwand Maslin. Courtesy photo

We-Ha.com will be publishing a series of essays/blogs/reflections on the issue of going to college – primarily a set of thoughts and musings, along with some practical advice, intended to support students and parents as they embark on this journey. While many of our readers are experts in this topic, many others are less knowledgeable and have little outside support. We hope this is helpful to all readers as they go through the various stages of getting into and getting something out of college.

By Adrienne Leinwand Maslin

Professor Maitland Jones, Jr. taught chemistry at Princeton University for 43 years – from 1964-2007. He held what is known as a “named chair”; he was the David B. Jones Professor of Chemistry. (David B. Jones was a member of the class of 1876 and later became a trustee of the University. The funding for this special designation was a gift to Princeton in 1927 from his daughter.)

When Professor Maitland Jones, Jr. retired, the designator “Emeritus” – a term to denote someone whose service was both lengthy and meritorious – was added to his title. After his retirement as a tenured professor at Princeton, Professor Jones took a position teaching organic chemistry on annual contracts at New York University. In 2017, he was voted one of NYU’s “coolest” professors.

But, in 2022, after teaching at NYU for 15 years, Dr. Jones’ contract was not renewed. According to the New York Times, 82 students out of 350 signed a petition against him saying the course was too hard and claiming Professor Jones was the cause of their poor test scores.

The same article goes on to explain Dr. Jones’ position: students are not studying as much and, in fact, don’t know how to study. And while some blame the pandemic, Dr. Jones and other educators say the pandemic only exacerbated a situation that already existed. Other faculty and teaching assistants in the NYU Chemistry Department claimed that many additional resources were provided to students but that students did not avail themselves of these resources.

In a Dec. 14, 2022 article in Inside Higher Ed, authors David Wippman and Glenn C. Altschuler, while not in complete agreement with Dr. Jones, point out that “At the height of the pandemic, many faculty relaxed their expectations for the quantity and quality of student work. This may have been an appropriate response to a public health emergency, but it came at a time when students were already doing roughly 40 percent less homework than they did 60 years ago.” They go on to say, “In higher education, many faculty report a decline in student focus and study skills, as well as patterns of poor attendance, late assignments and low grades.”

During my time in higher education, I advised students that, in order to be successful in college, they had to study six to nine hours per week for each three-credit course they were enrolled in. This might include writing lab reports for science classes, reading textbooks or other reading materials, writing essays, working with other students on a group project, creating artistic works or rehearsing for dance or theater performances, responding to homework questions, or conducting research in the library or online. A student taking a full course load of four or five, three-credit courses should, therefore, expect to study for nearly 45 hours each week. Being a full-time college student is like having a full-time job and I think it is helpful for students to approach their college experience with this thought in mind.

Now if you are picturing yourself bound to your chair with duct tape, with no time to get a cup of coffee, scratch an itch, or use the bathroom, let’s look at it in a different way. There are 168 hours in a week. Let’s say you get eight hours of sleep per night. This may be on the generous side for many college students but if you want to excel in college and maintain your health, sleep is important. So, do the math. That leaves 112 hours!

A typical course load requires 15 hours a week of class time. Again this is generous since most colleges use a 50-minute hour to give students a chance to move across campus in between classes. But we’ll go with 15. Now we’re down to 97 hours. Let’s subtract our 45 hours of study time and we’re left with 52 hours. Even if you hold a campus job for 20 hours each week you still have 32 hours left to do, well, whatever! That’s a lot of time left to eat, play a club sport, participate in student activities, go to parties, go to the gym, etc. (Being on a varsity athletic team is very demanding, particularly when traveling to other colleges for away games. If you play or are planning to play a varsity sport, please keep this in mind.) The point is that putting in a lot of study time does not preclude the fun stuff.

Aside from putting in the hours necessary to earn high grades, you will want to study in the most efficient and effective ways possible. Let’s take a look at a couple of ways to make studying more effective. To do this we need to talk a bit about brain science – in a very rudimentary way.

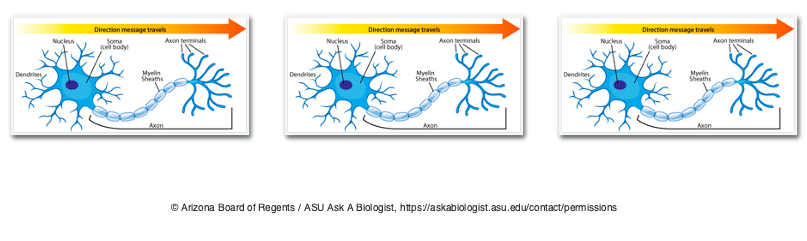

Our brains contain about 86 billion neurons that look like this:

Neurons use chemicals and electrical impulses to transmit information from one neuron to another through our brains. When we learn new material for the first time the connection or pathway between the neurons is not very strong. If we try to retrieve the information we frequently cannot remember it and may have to look it up. As we study it more and more, however, the pathway solidifies.

Imagine this, if you will: the left-most neuron above uses its axon terminals to tickle the dendrites of the middle neuron, notifying the middle neuron that it would like to transmit important information that you learned in class. The information travels down the axon of the middle neuron and arrives at the axon terminals. The middle neuron then tickles the right-most neuron and transfers the information. And so on down the line of neurons in our brains. Picture how these neurons react when the material is fresh and new. They can barely reach the next neuron no less give a little tickle. But when the information is really solid these things just fire – bam, bam, bam! When you sit in a college class you are encountering much material and information that is new to you. So how do you really learn this new material? How do you make it stick? How do you get these neurons to go bam, bam bam? Here are some suggestions.

- You read the textbook pages or other material assigned by the professor.

- You read other material on the same topic that was not assigned but that you find in the library, online, or in other textbooks.

- You look at all pictures and charts in your textbook and read the captions underneath. (You know the expression “A picture is worth a thousand words?” It’s frequently true. Sometimes a picture can convey information that would otherwise require several paragraphs of print. And sometimes that picture will really stick in your brain, supplementing and strengthening what you just read in the printed material. Additionally, pictures, especially those that are in color, are more expensive to publish than print material so if the picture is in the book it is typically a reflection of its importance.)

- You make flash cards of key words or concepts with the word/concept on one side and its definition or importance to the topic on the other.

- You use the flash cards periodically to test yourself on the material or you ask a friend to work with you on this.

- You talk about the material with other students in your class.

- You write down any questions you have about the material so you can ask your professor before, during, or after class.

- You answer practice questions and take practice exams.

Let me point something out about the suggestions above. In Nos. 1 to 3, you are taking actions that require you to take information in. When we read and when we listen we are taking information into our brains. Nos. 4 through 8 require you to get information out of your brain. When we speak and write we are getting information out. Strengthening the output pathways in our brains is just as important as solidifying the input pathways. If we only take information in, there will not be a strong pathway when it comes to getting the information out which is what you do when you take an exam. This is why the two best study methods are to teach the subject matter to someone else and to do practice exams. Both methods require you to get information out.

Further, when you teach the material to someone else, several other things happen. One is that you are hearing the information – i.e. taking information in – while you are speaking. And while you are speaking you are getting the information out. It’s kind of a two for one! The other thing is that the person you are teaching it to may ask you some interesting questions that you hadn’t previously considered, giving you another perspective when thinking about the material you are studying. (Unless, of course, that someone is your dog. Then your best pal can only look at you with ears pricked up and head cocked to one side! Unless it’s a very unusual dog!)

The strategies above are specific to studying material for better understanding as well as for exams but there are other steps you can take that will contribute to your overall success in college. Consider these:

- Take advantage of extra help; extra help is available in many forms and it should never be embarrassing to admit you need help understanding a concept or developing a particular skill.

- Most colleges have a tutoring center although the name may vary. Tutoring centers employ paid professionals and peer tutors who can help students throughout a semester or help a student on a one-time basis get over a particular hurdle or understand a singular concept. Some colleges also have separate math and writing centers. Take time to check them out.

- Visit with your professor during office hours. I’ve heard many professors lament that students do not come in to see them during office hours. Faculty enjoy having their students come in—to ask a question about class, get extra help understanding something specific, or just to say hi and have a conversation. They want to get to know you!

- Attend the more formal extra help sessions an instructor or teaching assistant might hold, typically prior to final exams.

- Join a study group. Study groups allow you to learn from others and teach others. Each member of a study group may understand what was taught a bit differently and can explain their ideas to the others. Being part of a study group is very similar to teaching material to others in the list of study skills above and, if you don’t take too much time gossiping or joking around, it can be a very potent way of learning.

- Attend every class – unless you have a very good reason not to (COVID, flu, etc.). Skipping class because you’re just not feeling it, is not a good reason. In most cases, classroom time is critical to your getting the full flavor of the subject matter being taught. The exchange of ideas between the instructor and the class and between and among class members can be exciting and is necessary to your understanding of the topic.

- Sit close to the front in class. Students who sit close to the front are usually able to maintain better eye contact with the professor, keeping them more engaged.

- Practice mindfulness. Mindfulness is the concept of being in the present, of maintaining an awareness of where you are and what you are doing. The reason it’s important is that practicing mindfulness will help you stay on track with your academic commitments amidst all of the activities a college offers that might lure you away. Mindfulness is what allows us to take a second or two to decide if we should get a cup of coffee with a friend or continue studying at the library. Whatever you do, it should be a decision that you make mindfully, considering the work you’ve gotten done, the work you have to do, and your priorities.

To do what I’m describing above is a lot of work. And it’s hard work. It takes time and effort. But that’s why you’re in college. Now clearly, if you’re a straight-A student whatever you’re currently doing is working for you. Or you’re just lucky! But if you are among the many who would like to improve their grades, or if you are challenged by a particularly difficult class, the methods above should help you get your best grades ever.

Adrienne Leinwand Maslin recently retired from a 45-year career in higher education administration. She has worked at public and private institutions, urban and rural, large and small, and two-year and four-year, and is Dean Emerita at Middlesex Community College. She has held positions in admissions, affirmative action, president’s office, human resources, academic affairs, and student affairs. Maslin has a BA from the University of Vermont, an MEd from Boston University, and a PhD from the University of Oregon. She is presently creating a TV/web-based series on life skills and social issues for 9-12 year olds believing that the more familiar youngsters are with important social issues the easier their transition to college and adulthood will be. Information about this series as well as contact information can be found at www.shesroxanne.com.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.