From the West Hartford Archives: Beachland Park

Audio By Carbonatix

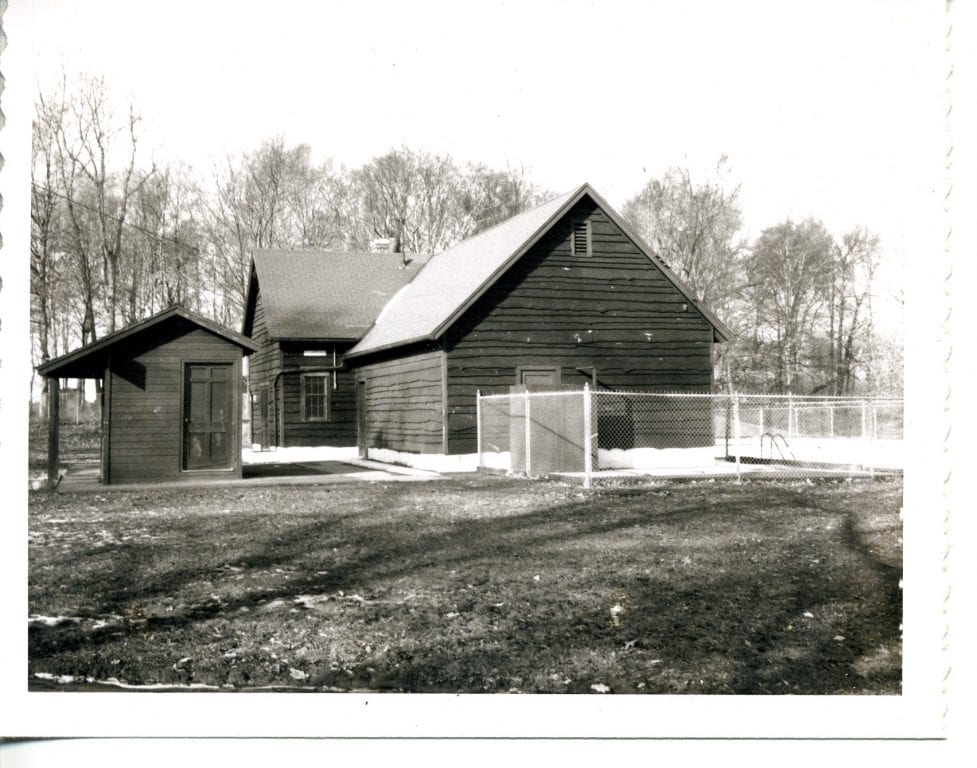

Vine Hill Creamery building in what became Beachland Park. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

Beachland Park is named after the Beach family, who owned and managed the Vine Hill dairy farm from South Quaker Lane to South Main Street for nearly a hundred years.

By the late 1920s, there was a growing need for public spaces where residents could relax and socialize. With a surge in the population, there was an increasing awareness of the importance of public health and the benefits of outdoor recreation for children and adults alike.

By 1930, there was an intense debate across town on where the land should be bought for a park and playground. The town was facing a lack of money for a site and people disagreed on whether the town should create two or three smaller parks rather than one large park. In the fall of 1931, a special referendum rejected a call to buy the dilapidated Charter Oak Park and brought the whole town back to square one (Charter Oak Park would be left for several more years to wither and die before being turned into a wartime factory).

To help resolve the dispute, the Beach family followed the referendum by donating 12 acres of their farmland land to the Town of West Hartford. The town council accepted the gift in April 1932. Work began that summer to trim trees, cut the grass, clear brush, level play areas, and build a baseball field and tennis courts.

The labor was funded by the finance board and town council, which appropriated $12,500 for hiring unemployed people to work on both Beachland Park and the Sedgwick playfield, specifically targeting people on welfare and alms lists. The U.S. was in the midst of the Great Depression and West Hartford, like many other municipalities, was under serious economic strain as unemployment soared and more people required public assistance. By the late summer of 1932, the town council was being asked to appropriate more funding, highlighting the inadequacies in the safety net at the time. Local public works programs like this one preceded the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, but they influenced federal initiatives like the New Deal from 1933 onwards.

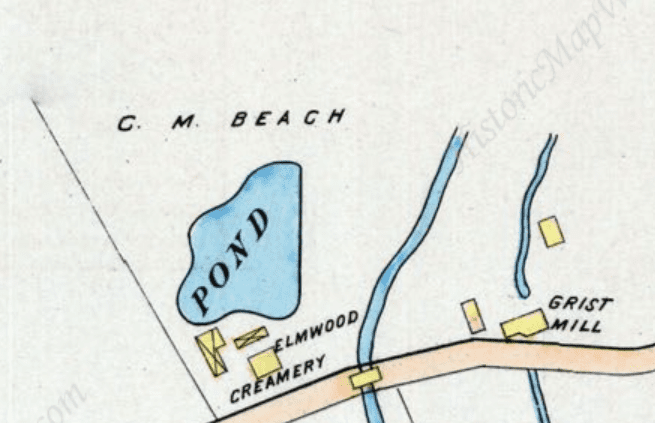

Map of Vine Hill Farm in 1896 – the iconic pond can be seen here in its original form and the Beachland Park clubhouse stands as the original creamery building.

The following spring, as work on the two parks neared completion, Town Manager Benjamin I. Miller pushed for an emergency appropriation of $8,000 for the employment of jobless citizens. Work on the baseball field in particular was accelerated “so that Elmwood residents … would get some enjoyment from the park this summer.” Beachland Park was unofficially opened to the public on Memorial Day 1933 with a baseball game between the St. Bridget’s Church Men’s Club and the Hartford Orioles (Elmwood lost 9-3).

To build on the work that had been done on the park, Elmwood residents lobbied into 1934 for the remodeling of the old Vine Hill Farm creamery building fronting on South Quaker Lane into a clubhouse. After a year of deliberation, the town approved the remodeling and the old dairy building was converted into a clubhouse and storage building for Beachland Park.

Funding was approved through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), an agency established under FDR’s administration during his first hundred days to reduce unemployment. FERA played a crucial role in stabilizing community development by injecting much-needed federal funds into local economies.

Going into the spring of 1935, West Hartford had expended nearly $70,000 in funding from the federal government for numerous projects, including new sidewalks, school surveying, storm water sewers, drainage on Wardwell Road, and snow removal across the town. Federal funding meant West Hartford could focus more attention on the parks. A plan in the summer of 1935 included development of the Fern Street Playfield (Fern Park) and better facilities for Smith School, Plant Junior High School, and Charter Oak, Center School, and Morley School, with nearly 40 new jobs being created and filled.

In the fall of 1935, the town approved the construction of a swimming pool and bathhouse at Beachland Park. In order to accommodate it, the town had to buy an additional 3.25 acres at the west end of the park the following spring from the Beach family. Funding and labor this time came through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the successor to FERA. The WPA took over many of the public works projects initially funded by FERA, with a stronger emphasis on creating employment.

In West Hartford, the WPA planned a comprehensive summer playground program for a number of schools and parks. Residents were unified on the need for further development of parks like Beachland. Construction of the pool employed 22 men, including 20 unskilled laborers, with the federal government shouldering 91% of the bill originally.

There were, however, a number of complications. Tragically, a 10-year-old boy drowned in the unfinished pool after hours. Labor was also inconsistent, scheduling was difficult, and the pool failed the chlorination test, delaying its completion until the following year.

Beachland Park pool, c. 1950s/1960s

Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

After the pool was built, residents were generally content with the work. Other parks in the area were rejected since recreational needs were covered by Beachland’s baseball and football fields, as well as a brand new playground, tennis courts, and electric lights a few years later.

The clubhouse was also used for more than recreation. At the end of 1937, a group of followers of Father Coughlin formed an offshoot of the National Union for Social Justice at the clubhouse. Father Coughlin, a highly influential Roman Catholic priest who reached a wide audience through his radio broadcasts, was initially supportive of FDR’s New Deal, but became increasingly disillusioned and felt that FDR was not being forceful enough to address the economic and social injustices of the 1930s. He felt that the president did not go far enough in reforming the big banks and accused him of being controlled by wealthy interests.

Coughlin’s Social Justice program called for the nationalization of key industries, the redistribution of wealth, and the establishment of a living wage, as well as the abolition of the Federal Reserve. He hoped to raise enough awareness to threaten FDR’s re-election in 1936 through a third party run, but FDR won re-election in a landslide. Additionally, with the rise of anti-Semitism, Coughlin began praising Nazi Germany and became supportive of the rhetoric across the pond, losing many followers in the process. A group of former members of the Coughlin movement, attempting to salvage his original principles without the baggage of the speaker, used the Beachland Park clubhouse as a meeting ground. Unfortunately for them, money was tight and by the end of 1938, they were broke and disbanded.

It is worth noting however that not only was Beachland Park a product of the Great Depression and the New Deal, it became a stage for politics against the New Deal, if only for a little while.

In the 1940s, Beachland Park was mainly used for escaping the oppressive heat in the summer months and enjoying the ice on the pond during the winter. The land around the park was also steadily bought from the Beach family by real estate developers for housing east of South Main Street. One of these tracts was known as Woodside Village and included the majority of the Beach family’s farmland, except for the homestead on Brightwood Lane.

Events like the water circus at the pool in 1940 attracted more than 1,000 people. Winter sports were expanded on – an ice-skating rink was constructed by the WPA in 1941 and skating competitions were made official. Beachland Park possibly featured a shooting range in the northeast corner of the park (the town apparently decided that a wire fence would prevent any injuries to children). Two paddle tennis courts and a basketball court were laid out, as well as an archery range.

As American involvement in World War II surged into 1942, many recreational events took on a patriotic or military note. Land was used more readily for defense housing (and the silt that washed down from the construction killed hundreds of fish in the pond). The annual water carnival featured war stamps for admission. Children at the park, between 12-16 years of age, were asked which branch of the armed services they would enlist in if they were of age. The old Vine Hill Farm water tower at the top of the park was used as a lookout for enemy planes.

In the summer of 1945, as the war’s end neared, the town council was urged to target the area at and around Beachland Park for a post-war recreation center at the northern edge of the land. The August 1945 water carnival was a massive and jubilant affair, drawing more than 2,000 people.

Flooding at Beachland Park in August 1955. Courtesy photo

Development continued through the 1950s, but the most notable event was the three-day flooding from the August 1955 Hurricanes Connie and Diane. Beachland Park was inundated immediately. Temporary repairs were made to nearby streets where cave-ins and holes were prevalent. The annual water carnival at Beachland was postponed indefinitely.

It was not the first time the Trout Brook-adjacent area was flooded and it would not be the last. Families sometimes had to move into the Beachland Park clubhouse if the flooding was bad enough. Continued flooding through the 1960s prompted years of intense flood control measures in Elmwood and beyond. By the early 1970s, a channel was constructed to carry Trout Brook from Beachland Park to New Park Avenue, with a dike to mitigate any flooding.

The park has seen many more changes in the last half-century, but its history tells a story of a continuous work in progress.

Former Vine Hill Creamery building in Beachland Park. Google Street view

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.