From the West Hartford Archives: Fern Street and Prospect Avenue, Northwest Corner

Audio By Carbonatix

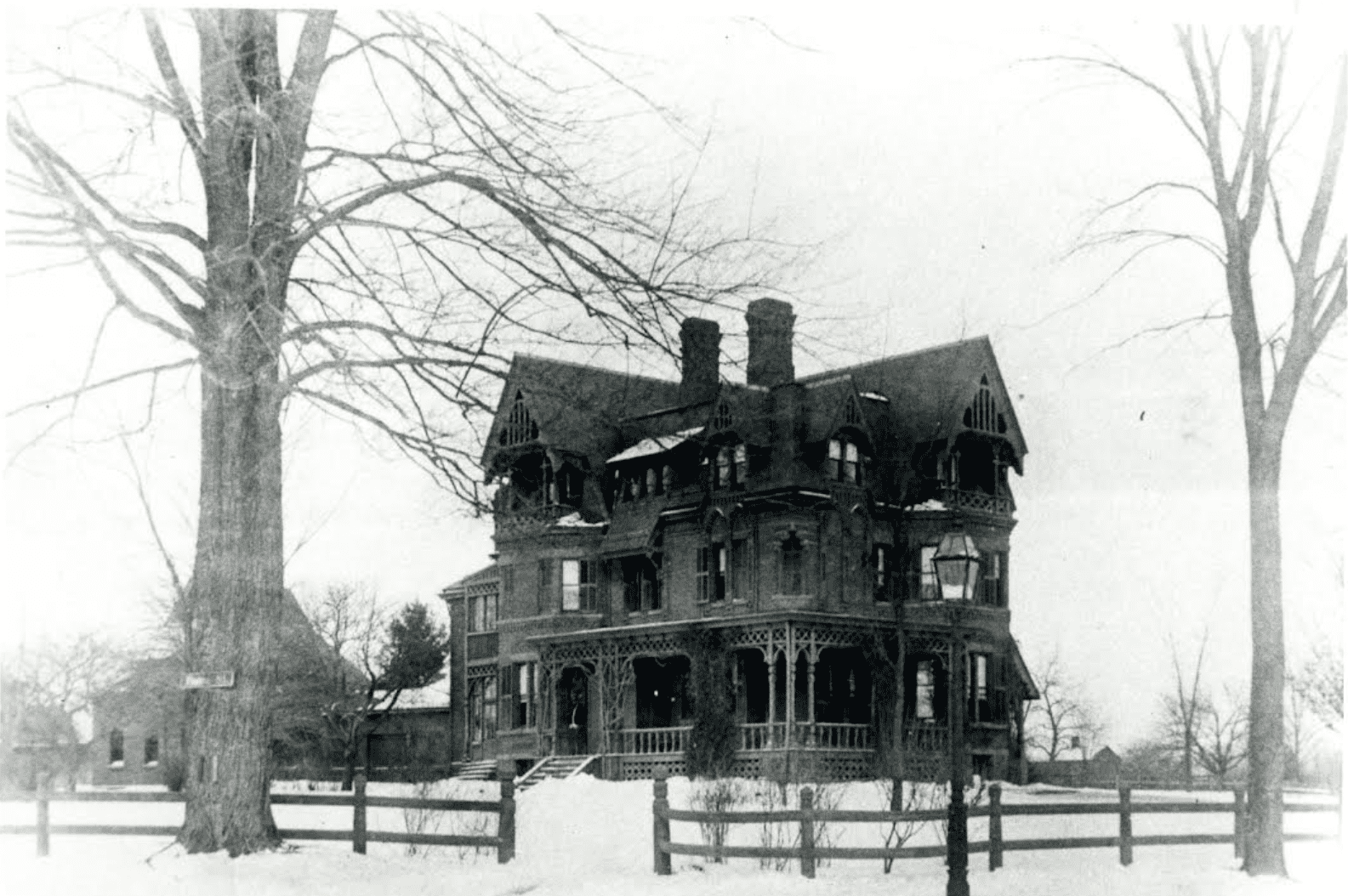

Mansion built for Yung Wing at the northwest corner of Fern Street and Prospect Avenue. Photo credit: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The northwest corner of Fern Street and Prospect Avenue was the site of the mansion of Yung Wing, a Chinese-American diplomat, in the 1880s.

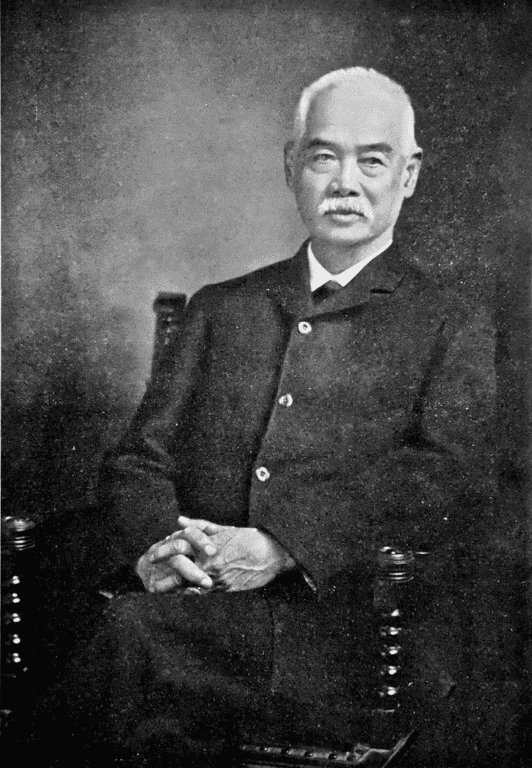

Born in 1828, he was brought to the U.S. at the age of 19 by a teacher and became the first Chinese student to graduate from an American college, receiving his degree from Yale in 1854. He was heavily invested in the educational welfare of Chinese students, organizing in 1872 a mission to bring over more than 100 students from China to study in the U.S. In 1874, he traveled to Peru to look into the conditions of Chinese wage workers. According to newspapers, he spoke out hotly against labor conditions in Lima and did not relent even when told his words might put his life in danger. For some years after, he was charge d’affaires at Washington, D.C (a de facto ambassador) and was appointed associate minister to the U.S., Peru, and Spain.

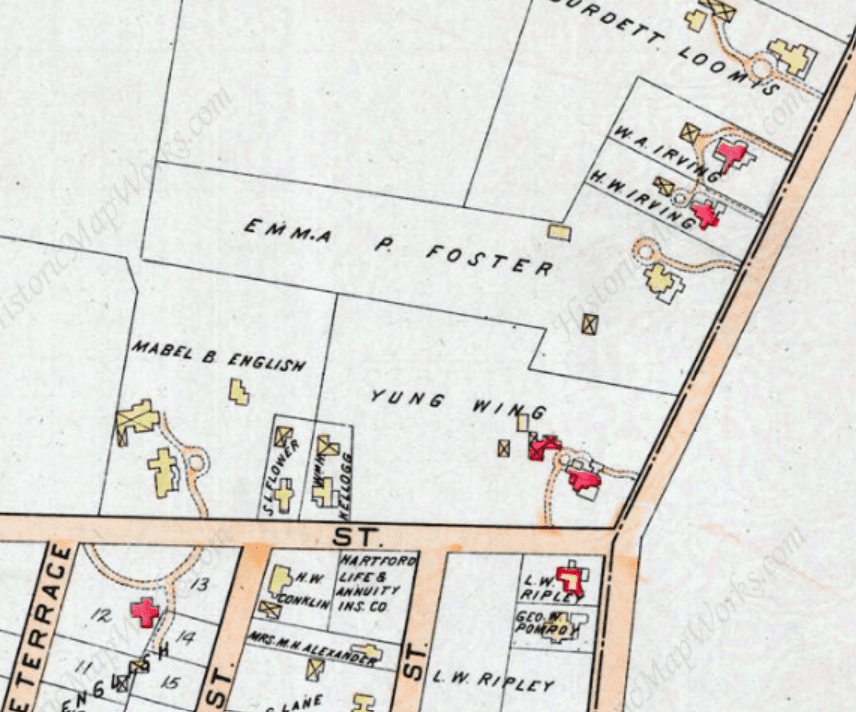

In the 1880s, the mansion shown in the photo above was built at the corner of Fern Street and Prospect Avenue for him and his wife, Mary Kellogg, who died in 1886. His brother-in-law, William H. Kellogg, employed by the Aetna Life Insurance Company, lived next door to the west of the house on Fern Street.

Active in Chinese politics, Yung was recalled back home as a result of the Sino-Japanese war in 1894-95 (which China lost). Imperial powers – including but not limited to the U.S., France, Germany, and Russia – had incrementally encroached on Chinese territory through foreign spheres of influence since the opium wars of the 1840s, either through the presence of Christian missionaries or by leasing coastal land from the decaying Qing dynasty. Yung, reporting on events in China, noted the scramble for colonies by the imperial powers for resources and the increase in social tension as resentment built up. In the summer of 1898, a coup by the Empress Dowager Cixi reacted to modernization reforms, which were considered too radical, and the main reformers were arrested and executed. Yung, who was involved in these reforms (mainly in the coal industry and the construction of railroads), was suddenly a threat and he fled to British Hong Kong from Shanghai.

Yung Wing. Photo: Portrait of Yung Wing from his 1909 book, My Life in China and America

The crisis, along with several natural disasters, was perceived by many anti-colonial, anti-foreign “Boxers” (rebels, who were named by the martial art they often practiced) as a result of foreign influence. The Boxer Rebellion starting in 1899 converged on Beijing and besieged the city to rid the country of foreigners. An eight-nation alliance of European countries brought 20,000 troops to China and relieved the siege. The defeat of the Boxers was one of the factors that contributed to the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912 and the collapse of the monarchy after more than 2,000 years.

During this era of unrest, in May 1899, Yung Wing sold the house at the corner in West Hartford to Arthur L. Foster, a Hartford businessman.

In 1902, upon attempting to return to the U.S., Yung was told that his citizenship had been revoked. New arrivals of Chinese immigrants, mainly on the west coast, starting in the 1840s were crucial to the American labor force, first in gold mining and then in the post-Civil War boom. Chinese immigrant workers were heavily used in the building of the first transcontinental railroad in the 1860s. Economic depressions in the 1870s however helped fuel already existing anti-Chinese sentiment as a foreign force that was stealing American jobs and the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed by the U.S. Congress in 1882.

Many of the Chinese students who had been brought over in the 1870s under Yung Wing’s initiative were shipped back home. Yung, with his standing in the community in Hartford, managed to evade exclusion for many years until after he had left the country in the 1890s. His revocation of citizenship didn’t entirely stop his return in 1902 to Hartford, but Connecticut was not immune to the fierce anti-Chinese sentiment that had spread across the U.S. during the previous decades.

Arthur L. Foster, a clothier, owned the mansion in West Hartford from the time of the purchase in 1899 until his death in 1922. He had conducted the clothing store of A. L. Foster & Co on Asylum Street in Hartford for 38 years. Upon his death, the estate passed to his widow (after a lengthy legal dispute over the will) and from there to a site for apartments, which were constructed starting in 1926. Built over time, these are now the residences at 777 & 779 Prospect Ave and 180/182/184 Fern Street at the northwest corner. Prospect Avenue and Fern Street had only developed since the 1870s, but the mansion had been a witness to the development of Elizabeth Park and the growth of the east side of West Hartford at a critical juncture in its history until it was eventually torn down.

An 1896 map showing Yung Wing’s house on the corner

One must now return, though, to the end of the life of Yung Wing, the proprietor of the mansion in West Hartford. After his return from China in 1902, he lived in Hartford, sometimes with his children out of state. In 1909 he wrote his autobiography, reflecting on his upbringing and accomplishments diplomatically and commercially.

It is also important to recognize that in an era of newspapers and word of mouth, the thoughts of Hartford area people on China – only recently introduced in the news as a result of foreign involvement – were undoubtedly influenced by Yung Wing’s opinions. As an authority on the political situation overseas, the newspapers often reprinted his lectures or other correspondences, which would have shaped the opinions of local people. During the political crisis in 1911-1912 that saw the abdication of the last Chinese emperor and the end of the Qing dynasty, Yung Wing was essentially the vessel of important news to people in Hartford on the situation.

At the establishment of this new republic of China, Yung died in April 1912 at his home on Sargeant Street. Some sources say he lived in poverty until the end of his life after his return from China. A note in the Hartford Courant, however, gives an idea on his legacy in the local eyes: “Yung Wing is the man who woke up China. All his later days, he had dreamed of the Chinese republic, which he foresaw; of which at one time it was conceivable that he might be President. He was the Moses of that innumerable people.”

Current view of the northwest corner of Fern Street and Prospect Avenue. Google Street view

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.