From the West Hartford Archives: M. J. Burnham’s in World War II

Audio By Carbonatix

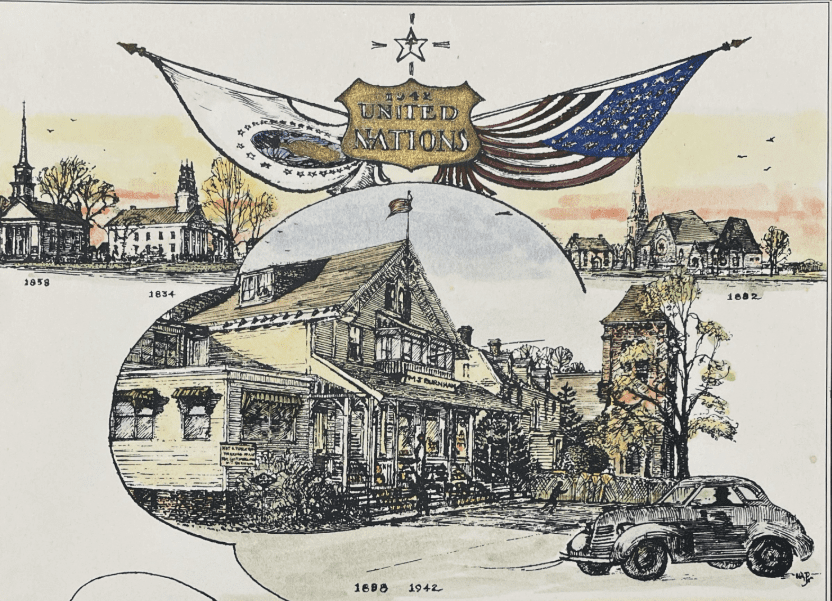

Wartime civic tribute to the United Nations coalition in the context of West Hartford, published by M.J. Burnham's. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The United Nations, now more known as the global organization established after victory in Europe, was formerly used to refer to the countries that banded together to defeat the Axis powers when the U.S. entered after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

On Dec. 7, 1941, West Hartford became involved almost immediately when local pilot Gordon H. Sterling was shot down and killed in action by the Japanese after taking down one in his sights.

Sterling was originally reported missing in Hawaii and his parents, living on Argyle Avenue, were notified the following day. World War II had been raging for a little more than two years and the U.S. was paying close attention to events across the sea when the attack was launched. Overnight, West Hartford became tied to the bombing in Hawaii and, like many Americans, it galvanized their motivation to enter the war and defend liberty against the Axis onslaught.

Local reporters framed Sterling’s sacrifice as validation of his faith, his morals, his education in West Hartford, and his participation in a democratic society. The Hartford Courant justified sacrifice, prepared readers for more losses in the months and perhaps years to come, and encouraged civilian support for the upcoming war effort. The U.S. declared war on Japan, and Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S. Mobilization began almost immediately in the face of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines and other American outposts.

On Jan. 1, 1942, 26 countries signed what became known as the Declaration by United Nations. These countries pledged not to make any separate peace agreements with the enemy, preempting any one country from cutting a deal independently. President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose the name, rejecting phrases like “Associated Powers” and “Allied Powers,” which felt more tied to the era of World War I than the forward-thinking idea of unity of peoples. Later an institution for the pursuit of global dialogue, the original United Nations was purely a practical war coalition.

In 1942, Myron J. Burnham’s grocery store published the featured poster, a wartime civic tribute to the United Nations coalition in the context of our little town. Local young men were enlisting or being drafted. Rationing was beginning. Communities like West Hartford were full of local businesses and institutions that were ready to sign onto the effort in a civilian capacity, even if only for messaging.

The bottom of the placard (not pictured) reads: “We are watching with keen interest the unfolding of events that will make secure the future of our country for all time to come; events in which you are playing so vital a part. Our thoughts are of you every day. May God be with you all the way. – The Burnham Family.”

Even a brief glance at this artwork makes it clear that West Hartford’s institutions could become the face for the war effort: churches of multiple denominations to signify a moral foundation across faiths, the grocery store for economic sustenance, the town hall for authority in governance, an automobile for modern development, and a flag atop the store to signal patriotism against the forces of evil.

By early 1942, rubber supplies from Southeast Asia had been cut off by Japan. Automobile manufacturing was being converted to war production and civilian vehicle production essentially stopped, with severe restrictions on tires. Purchases of cars, tires, and inner tubes, for example, needed official approval by the ration board and most of the approved purchasers had occupational justification: police, oil companies, electrical engineers, and transportation companies.

M. J. Burnham’s grocery store was issued certificates for four tires and four tubes in March 1942, most likely for operational delivery trucks. Beyond the messaging, Burnham’s essentially was a critical wartime service. Food was an important marker of the war effort. Not long after this purchase, Burnham’s aligned themselves with federal nutrition campaigns and national health messaging. Strong workers were needed for strong production for a strong military.

Burnham’s began promoting lean meat, fish, vegetables, milk, eggs, butter, and cereals under the guidance of the federal government. That summer, the store served as a distribution center for certain charitable drives, including one to salvage old phonograph records in order to make new records for the benefit of the armed forces.

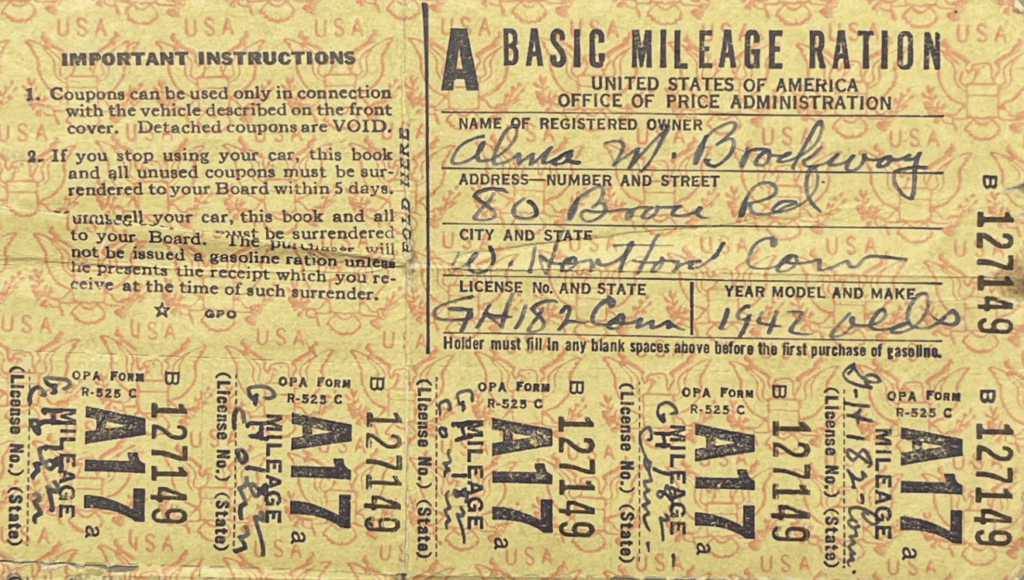

Ration gas cards of a West Hartford resident, Alma Brockway, during the war. The Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society has many of the family’s collected receipts from Burnham’s grocery store in the late 1940s into the 1950s before it closed. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

The early inertia wore off though by the end of the year and the effects of a deepening war were being felt in West Hartford. Labor was being absorbed into factories and the armed forces, month after month, and manpower shortages were severe. Burnham’s announced in January 1943 that they were suspending delivery service and phone service. “It is impossible to get sufficient help for delivery service,” they announced. “The most regrettable part is our inability to take care of those friends who have given us their patronage through good times and bad, and to whom we are indebted for much of our success.”

Their commitment to civilian support remained though. They joined a statewide committee under the Food Distribution Administration to combat the shortage of goods. They signed onto a justification for food rationing across the country and solicited donations from employees for the Red Cross. Burnham’s touched every aspect of food. Since commercial agriculture was strained and transportation was limited, the government encouraged citizens to grow vegetables at home to reduce pressure and support supply chains.

By 1943, nearly 40% of U.S. vegetables were grown in so-called “victory gardens”. Burnham contributed a plot of land to the Brace Road club for a victory garden “to work together for a vegetable victory.” The Allies were making a slow but steady advance in the Pacific after turning the tide and stopping the advance of the Japanese at Midway, Guadalcanal, but the home front saw immense pressure. Draft calls were high, production was soaring, and labor shortages struck at local communities. The draft threatened key food producers and grocers in Connecticut, prompting the industry to lobby for deferments. Myron Burnham was included in the committee that wrote the appeal to the War Manpower Commission.

It is a bit interesting for a local grocery store under intense strain, suspending delivery service and short on manpower, to continue to put so much effort into the civilian war effort, almost at the expense of its business and staff. Some businesses were hit so hard that they legitimately closed, but they were not the norm. Most businesses were surviving by high consumer demand and morale. In wartime, West Hartford customers looked for continuity in their routines and Burnham’s offered a reliable supplier and a store that worked relentlessly in favor of the war effort.

In January 1944, West Hartford began its participation in the Fourth War Bond Campaign. Burnham’s had a booth at the drive headquarters (Victory House) at 992 Farmington Avenue, helping to coordinate the sale of war bonds to help fund tanks, ships, planes, and ammunition overseas. By war’s end, Americans had purchased over $185 billion in war bonds. As the drive got started though, local officials worried that residents of West Hartford were not buying enough bonds, using the word “complacency.” Urgency was fading and people increasingly felt the Pacific theater was progressing well enough that further funding was not as important.

While this concern lingered though, M. J. Burnham’s was granted authority to serve as a sub-agency of the West Hartford Trust Company, meaning they could accept bond subscription applications, issue registered bonds, and serve as a station for bond sales. Essentially, the store became an official distribution point for the U.S. Treasury.

A week after the Normandy landings on D-Day, West Hartford launched its Fifth War Bond Campaign, with a quota of $5 million. The West Hartford Trust Company, with M. J. Burnham’s, implored residents in town to raise the necessary funds for the boys in the armed forces to “save their lives and to end this War before another Christmas comes.”

Another Christmas would arrive during wartime, but by early 1945, it was clear that the war would be won by the Allies (but at a cost). Newspapers like the Hartford Courant increasingly framed the war as entering its “final phase,” at least in Europe.

Like the political leaders that met at various summits on the eve of the war’s end, the movers and shakers of the food industry met to prepare for what would come next. On April 16, 1945, just four days after the shocking death of President Roosevelt, several grocers met at Burnham’s store in West Hartford under the label of the Independent Grocers Association. The goal was to “protect and promote the interests of retail merchants and to create better relations between Mrs. Consumer and the merchant on food problems of today.” Even though Germany was collapsing and America was island hopping to Okinawa, the wartime economy still had price ceilings, ration coupons, and shortages of goods. Grocers were itching to plan for the return of normal life and commerce.

Germany surrendered three weeks later and Japan surrendered in August. After the fighting ended, the U.S. Treasury launched one last nationwide bond campaign to pay off remaining debts and stabilize postwar finances. A “MAMMOTH Victory Bond Show” in Hartford featured “Kiss and Tell” (starring Shirley Temple), a Coast Guard band, and a prize RCA radio. This festive and triumphant campaign looked to soak up cash and maintain stability during a potentially painful transition back to a normal economy.

Burnham’s pitched in to pay for the advertisement of this show. Burnham supported the consistent buying of supplies by housewives as rations were loosened into 1946.

A little over a decade later, M. J. Burnham’s was closed and demolished to make way for a parking lot for the First National grocery store in 1958. It survived two world wars, but died at the hands of the all-powerful supermarket. It was a sign of things to come.

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Sterling Field, behind Charter Oak School, was named in memory and honor of Gordon Sterling, highlighted in this interesting piece. I grew up on Argyle Ave., as he did, and played youth football there for many years as we did Hall HS home FB games; Hall had no field next to the school building (which is now the Town Hall, or the “Old Hall” as many elders still know it) so we bused to Sterling Field to play our games. FYI