From the West Hartford Archives: New Park Avenue Brickyards

Audio By Carbonatix

Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The core of Elmwood’s industrial background was its large deposits of clay that were concentrated in the southern part of town. Businesses that utilized this clay, like Ebenezer Faxon’s or Harvey Goodwin’s potteries, as well as individual brick kilns, dotted the section of New Britain Avenue where New Park Avenue would later be laid out. Manufacturing was fueled by and contributed to the construction of the railroad line through Hartford and Newington in the mid-1800s, with a freight stop located at New Britain Avenue. As a result, large organized brickyards were built along the railroad line where it intersected with Trout Brook, which provided a consistent source of water for the industry.

One of the first major companies in the area was the Hartford Brick Company, which was organized by Goodwin Pottery officer Wilbur E. Goodwin and real estate magnate Frederick C. Rockwell in 1894 on the east side of New Park Avenue. They secured an extensive clay bed and a plant with the capacity of 40,000 bricks per day under 40 employed men. Drying racks could handle a million bricks and a kiln shed of several million.

Their first office was in the Elmwood grocery store and market on New Britain Avenue, which the brick company owned and controlled. Later, they built a new office on the west side near Talcott Road.

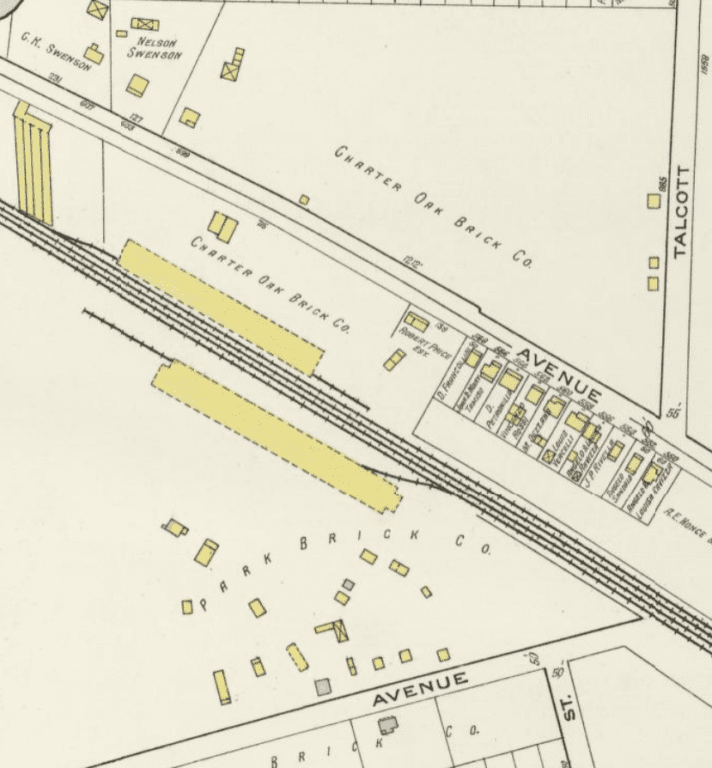

On the east side of the railroad tracks in a parcel of land bounded by Oakwood Avenue and Brixton Street was the Charter Oak Brick Company, opened less than a year later by a New Haven man. The companies built boarding houses on both sides of the railroad for laborers, who were mostly newly arrived Italian, Polish, French-Canadian, or Irish immigrants. The company experienced a difficult number of early years and was bought out by new management in 1898 after a bankruptcy. It was then renamed the Park Brick Company.

The brickyards on both sides – Hartford Brick and now Park Brick – supplied bricks to new construction in the Hartford area through the early 1900s, including for a brand new Elmwood School at the corner of New Britain Avenue and Woodlawn Street, now the site of the Faxon Library. Demand increased as the town grew and business became more formalized, but working-class vices remained a problem.

Several employees were arrested over the years for assault, drunkenness, breach of peace, cockfighting and gambling, and trespassing at Charter Oak Park and Luna Park. The town hired additional constables to keep the peace at the parks. The boarding houses were also easy targets for disease. An outbreak of smallpox in May 1902 quarantined 40 French-Canadians at the Hartford Brick Company.

By 1912, Elmwood was growing quickly with the help of the trolley line through New Britain Avenue – besides the brickyards, the Whitlock Coil Pipe Company; Bennett Manufacturing; Eastern Chemical; Abbott Ball; Petrossi Manufacturing; the remaining activity of Goodwin Pottery, and the Oleson Box Factory were running strong.

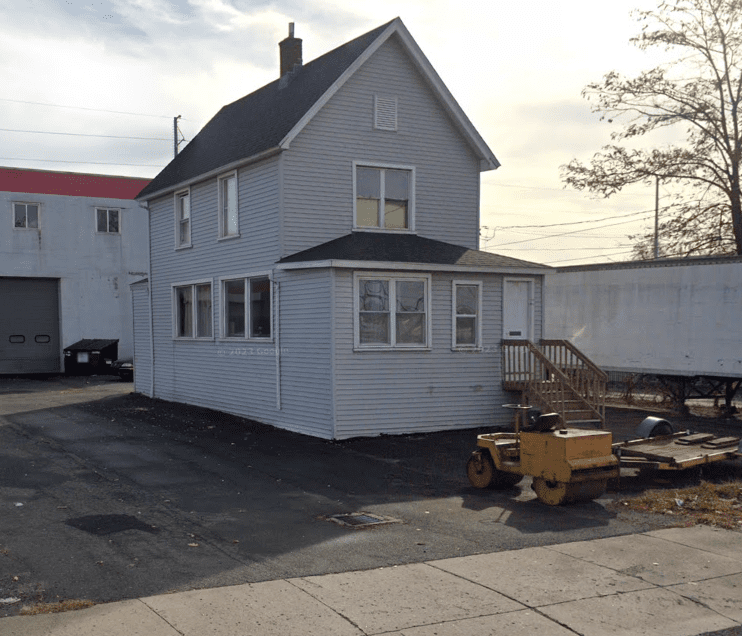

The Hartford Brick Company was bought out by the Phoenix Brick Company, which was itself bought out by another Charter Oak Brick Company. The surrounding streets were built up by demand for workers in these factories. South Street, for example, was lined with houses for workers at Whitlock Coil Pipe. Two- and three-family houses were built along New Park Avenue and New Britain Avenue to house the brickyard workers. Only a few of these houses remain, like 552 and 568 New Park.

In the fall of 1929, the president of the Charter Oak Brick Company shut the plant down out of a desire to leave the industry. This opened up the land on both sides of New Park Avenue for development. The town considered purchasing the clay beds for use as a filtration bed for sewage. Land on the west side, where the office had been, was used by the brick company as a public dump after brick work was discontinued. In 1937, the town finally bought it.

1917 map of New Britain Avenue and Talcott Road, with a row of boarding houses rented to workers at the brickyards on both sides of the railroad

The former brickyards became ideal sites for industrial buildings during and after World War II. The Adley Express Company bought land in 1938 at 580 New Park Avenue from the Charter Oak Brick Company and built a freight terminal, which opened in November 1940.

600 New Park Avenue. Google Street view

The Walton Company, small tools manufacturer, bought the brickyard land south of the terminal in 1943 for development intended for after the war. It was built at 600 New Park Avenue starting in the spring of 1947 and still stands there today. When it opened in 1948, the company employed 23 men and women, manufacturing electrical foot control switches and tap extractors used by automobiles, farm machinery, and aircraft and machine tool manufacturers. In 1950, a $70,000 wholesale liquor warehouse was built at 586 New Park Avenue between Walton and the terminal.

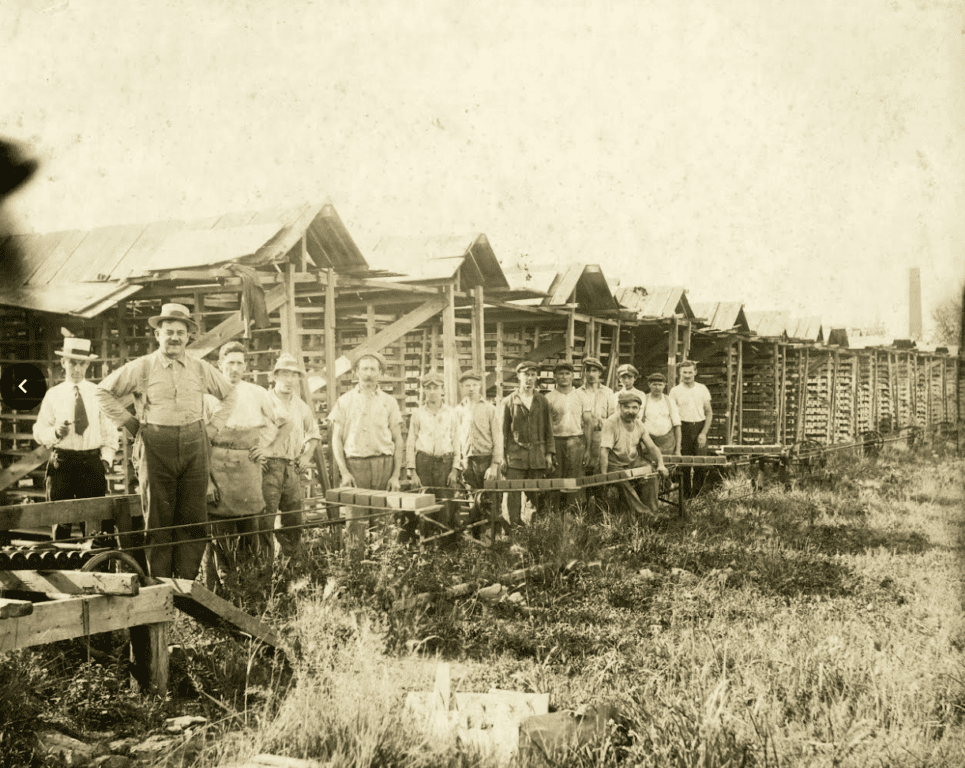

Workers at the Charter Oak Brick Company

Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

On the other side of the railroad tracks at Oakwood Avenue and Brixton Street, the brickyard of the Park Brick Company was sold off by the late 1940s and used for industrial buildings starting in the 1950s.

Of course, while this article focuses on the brickyards of New Park Avenue, the Kane brickyard must also be discussed. Many West Hartford brick houses and chimneys in the 1920s and 1930s were supplied by Kane bricks (including my own). Started as the Dennis brickyard on Prospect Avenue, Michael Kane had been hired by Thomas Dennis at the plant there as superintendent. Kane was born in Ireland in 1847 and came to the U.S. by way of North Haven. Upon his arrival in Parkville in Hartford in 1873, he started manufacturing bricks. His early work shipped bricks to the building of Trinity College in 1875, as well as the State Capitol building under construction.

After Thomas Dennis’ death, Kane bought the Prospect Avenue brickyard in West Hartford in 1905, where the business was conducted through the 1930s. The site of the Kane brickyard also provides a good example of the difference in how social groups integrated into West Hartford. The brickyards employed dozens of immigrants from French Canada and Europe and while they were often of low-income status, consistent work and a place to live afforded these families a foundation for social mobility. Several Italian families, for example, worked first in the brickyard and then advanced to their own practices, either in construction or in larger factories. They lived in town with family and were able to develop land and single-family houses in the surrounding area, like Hillcrest Avenue or South Quaker Lane.

This is one of the last remaining buildings that were built in the 1890s to house brickyard workers on the east side at 568 New Park Avenue. Google Street View

After the Kane brickyard was discontinued in the 1930s, it became the site of the government-funded WWII housing project known as Oakwood Acres in 1943. Federal law prohibited the formal exclusion of Blacks from this housing, but white residents, horrified by the idea of Black families moving into the area, exploited a loophole by accepting applications only from “Negroes with essential West Hartford industry jobs.” At the time, only six Black families qualified and they did not show any interest in living at Oakwood Acres.

This kind of technicality kept Oakwood Acres exclusively white and was used to exclude certain people even when it was officially illegal, helping to cement the racial makeup of some neighborhoods for decades to come after the war. In other cases, word of mouth was enough to exclude groups, like Roman Catholics on Stoner Drive and Wood Pond or Jews on Foxcroft Road. At the time of the brickyards being open, its employees were from a social class that would have been considered the “low-class” or “slum” of West Hartford by larger and wealthier residents, who would have seen constant news about liquor raids, fights, or gambling rings. As far as social mobility goes, there was a defined hierarchy that was driven by the decisions made by companies and residents alike.

A drive down New Park Avenue today shows no traces of the brickyards that were such an important factor in the development of the area. The rich clay deposits that were located in this section of Elmwood provided the foundation for the large brick works that would use the railroads for shipping. Immigrants and native-born Hartford residents used the trolleys in the 1890s and 1900s to get to work and some lived in boarding houses on site, helping accumulate more and more people to the area. New Park Avenue therefore became a central hub for the families who immigrated and established a foothold in the south end of town.

After the brickyards were dismantled in the 1920s and 1930s due to the decline of the brick industry, the land became ideal for use by the town for waste collection, industrial production, or warehousing. Some of these buildings remain today; other sites have been torn down and further repurposed for new housing not seen in decades. From a purely historical standpoint, the future of New Park Avenue is hard to predict, but it is bright.

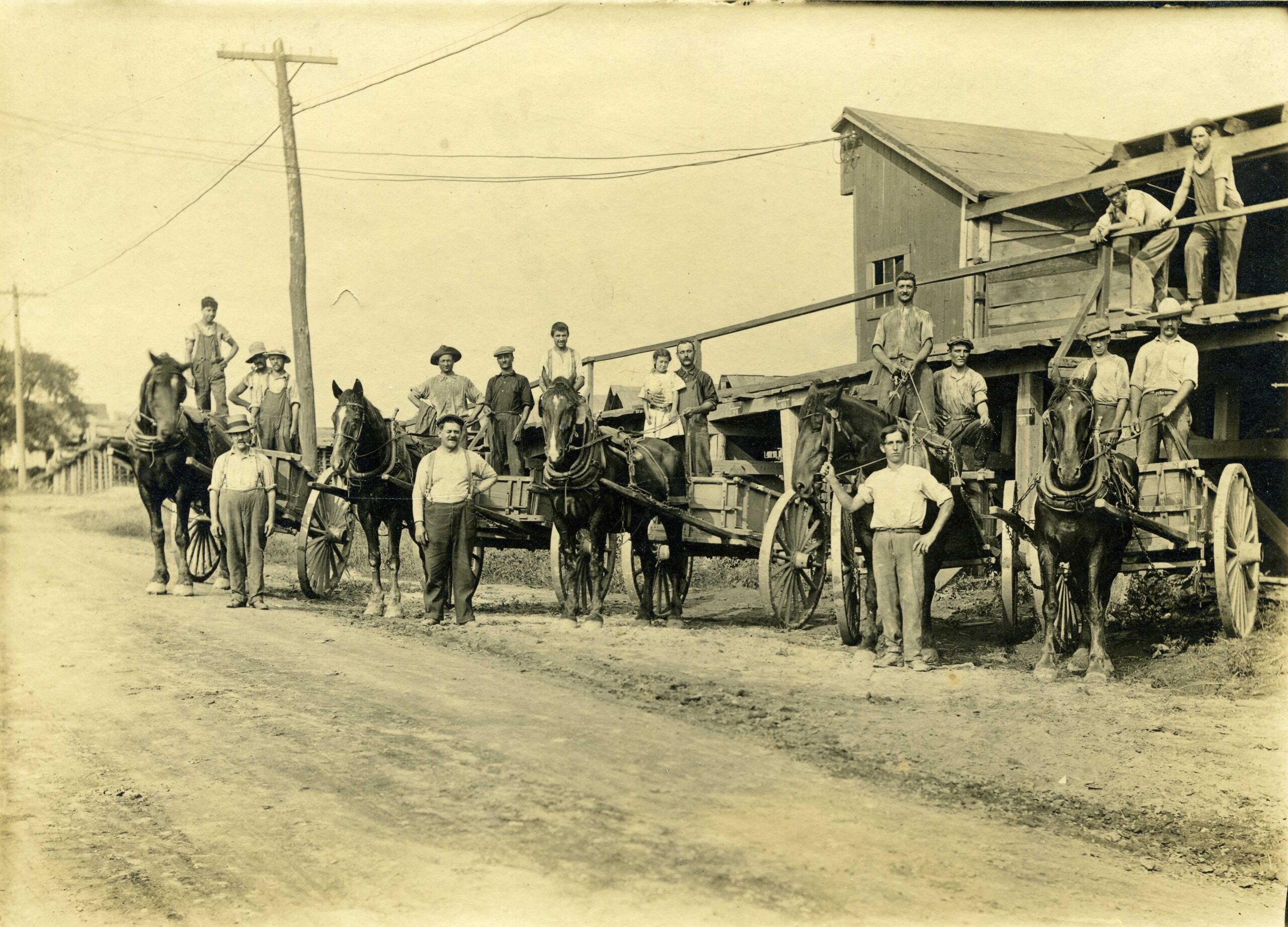

Another view of New Park Avenue during its brickyard era. The brick works and the shed of the Charter Oak Brick Company can be seen in the background next to the railroad. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

We lived in the Kane home at 291 New Park Ave. My mother rented it from her cousin Elizabeth Kane. There was a small area of woods that had deposits of coal and bricks. This has since been removed when the truck company took over the Carpenter Steel building