From the West Hartford Archives: Trout Brook Ice & Feed Company

Audio By Carbonatix

Trout Brook Ice & Feed Co. ice harvesting operation, c. 1907. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This is a photograph of the site of the Trout Brook Ice & Feed Company’s ice harvesting operations north of Farmington Avenue, taken around the year 1907.

Before the company was even founded, Trout Brook was a central fixture in the Center and was host to a sawmill and gristmill at the dam on Farmington Avenue. William Hall suggests that this mill, called Brace’s Mill, was one of the earliest, if not the first, gristmills in town. Water power was used to grind local farmers’ grain into grist, which was used to make flour. It became the property of Benjamin Gilbert and later his son, Seth, who inherited the carriage shop and gristmill in the 1870s.

In 1879, Edwin Hopkins Arnold purchased the property and founded the Trout Brook Ice & Feed Company with his son Frederick. They carried on the gristmill and set out to form an ice company. They also intended to continue a blacksmith shop and carriage shop, but just a year after it was purchased, the whole property was destroyed by fire.

Arnold was born in East Hampton in 1830 and came to West Hartford with his family when he was a child. The Arnold family settled along Farmington Avenue near Arnoldale Road (not surprisingly named after them). His first wife, Mary Augusta Flagg, died only a few years after they married and he re-married soon after in 1861 to Harriet Wadsworth, who would survive him by more than two decades.

As with most businesses, the early years were spent building up the infrastructure. In the fall of 1880, building on essentially ashes, Edwin Arnold built a large ice house on the west bank of Trout Brook, east of the Center, which took a year to put up. Ice was sawed into blocks from the frozen pond north of Farmington Avenue in the winter and transported up a wooden runway into this icehouse. The blocks were then insulated with sawdust and stored during the rest of the year in preparation for delivery to households. The runway was powered originally by steam and a long rope and pulley system, but as technologies improved, the company was able to order a 20-horsepower electric motor which could run it.

When it would rain, holes were drilled into the ice blocks to allow the water to run through them and better lift them up the runway, rather than weigh them down.

A few years into the business operations, Arnold raised the dam of the mill pond 18 inches to generate more power for his gristmill at the brook. The water flooded the lands of owners along North Main Street and Fern Street, so in 1886 he was forced to pay damages. Despite that, the town had a healthy demand for ice and so the Arnolds supplied it.

By 1895, the company had almost a dozen delivery wagons and 40 employees. They had steadily increased their ice storage capacity in new ice houses and their stock of horses. That year, they added harness making to their business and constructed a brick harness house near the horse barn. With the development of the new trolley line along Farmington Avenue and the subsequent increase in the population around the Center and beyond, the company had a consistent demand for new workers (and more ice from neighboring ponds).

In the late 1890s, Arnold built a number of tenement houses around Trout Brook to house workers, who were often poor residents local to Parkville or immigrants living in downtown Hartford. Some were West Hartford residents, like Lars Johnson, a Swedish immigrant who served as mill foreman for 14 years until his death in 1903.

With an increase in consumers and workers came a surge in demand for ice itself, as the main pond wasn’t sufficient to supplement their operations. In 1901, the company bought the former Scarritt & Smith gristmill and pond on the North Main Street branch of Trout Brook, north of the current site of the American School for the Deaf. In the years that followed, the company leased ponds in several other towns as well, shipping the ice into West Hartford or Hartford from afar in order to distribute it to residents.

Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Typical of the time, the company had its fair share of workplace accidents – horses went through the ice and had to be rescued every few years; countless workers broke limbs and suffered from frostbite; and the employees, like John Smith in 1898, fell off the wooden runway at a regular frequency. A young man stuck his foot with an ice pick and had to be carted back home to Parkville. Herbert Cook, a builder, was caught on the elevator during an ice “run” and was thrown to the ground headfirst in 1903. One of the ice houses caved in during the spring of 1912. Delivery wagons consistently crashed into trolley cars along Farmington Avenue.

These casualties of business, some life-threatening, were contrasted with the ice pond’s casual use by the townspeople. When it wasn’t being harvested, the ice company’s pond was the perfect place for sports, like polo. The West Hartford Curling Club, introduced in the fall of 1907 by several Scottish locals, used the pond for a few years before being kicked off.

Over the years, as the Trout Brook Ice Company’s business expanded, the pond became less available for these leisure seekers and new sources had to be found (or created). Therefore, a new skating pond was dug out in 1912 behind the new Center School, which later became the Whitman School and now the police station on Raymond Road. This pond became the go-to spot for both competitive winter sports and casual enjoyers alike. It didn’t stop some people from fishing on the Trout Brook Ice Company pond, soliciting employees with alcohol, or trespassing for the sake of trespassing, but the local constables found plenty of work on the site. Indeed, the first Sunday session of court in West Hartford’s history was held to hear the case against trespassers who were fishing in one of the company’s reservoirs.

In 1905, the founder Edwin Arnold died at his home at 892 Farmington Avenue (his house was later torn down and replaced by condos at the corner of what is now Arnold Way). Arnold had witnessed the first traces of suburbanization from the foundation of the company with the trolley and the first boarding houses for company workers, but his son, Frederick W. Arnold, who had helped since the beginning, now took the reins.

Frederick was more active in town affairs than his father, mostly due to the very nature of the town’s growth and the number of opportunities it presented. He led the Chamber of Commerce, originally the Business Men’s Association, as president during the WWI era, he supported the transition of town government to a town council afterwards, and was heavily involved in real estate along Farmington Avenue, including the neighborhoods on the corners of Quaker Lane.

With this kind of forward thinking, he leaned into the many modern improvements that could be made to the Trout Brook Ice Company plant. Electric lights were installed along Trout Brook and a steam heating plant was put up to heat the shops and offices starting in January 1910. Rather than having to wait for the sun to come up, harvesting went on day and night in the winters. In 1912, the company made one of the biggest investments in its history – Arnold purchased a significant amount of farmland from Farmington Avenue to Tunxis Road and built a reservoir at the south edge of the property, which is now Woodridge Lake.

The layout of Tunxis Road was fundamentally altered to run around it into Farmington and a second storehouse was built along what is now Waterside Lane. Freight railroad tracks were laid across Buena Vista to this new ice pond and allowed new sources of ice to be shipped to the main house in the Center.

Frederick W. Arnold, president of the company from 1905 to 1927. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

In 1914, two years after the new reservoir, the company closed out its grain business and focused exclusively on ice harvesting. The old gristmill and grain building were renovated into two offices the following year, which were rented to a men’s and women’s tailoring shop run by Samuel Gelfand of New York. An old structure on the property from the early days of the company was remodeled into a two-story building, with four offices in front and on the ground floor, and tenements to be rented on the second floor.

With some of the extra space, Arnold also rented one of his garages to Seymour & Michaels, who had formed a partnership to deal in automobiles. This early location gave them a significant boost and they quickly became one of the first and leading auto dealers in West Hartford in the 1910s. It also was a bit of a clue for the future of this area.

Arnold was also a contributor to the future Trout Brook Drive. In 1916, a landscape architect pushed the town to acquire land along the brook for a road, which would allow the building of houses along it. This “Trout Brook Drive project” included land that Arnold owned at the junction with Farmington Avenue and which later helped establish the full Trout Brook Drive in the 1930s.

During World War I, domestic demand for ice surged as shipments were routed instead to Europe, but after the war ended, trouble began for the Trout Brook Ice Company (and for the ice industry itself). New refrigeration methods, which had been developed before the war, steadily sucked away the necessity for a localized ice company and later electric motors allowed the individual homeowner to have the same capability of an old-school ice company. An accident at the plant in 1920 seemed to foreshadow the company’s decline – on January 5, the ancient wooden runway, which had been in operation since the beginning, collapsed during one of the ice runs and injured three employees. They sued the company for damages, claiming the ice house was not in proper condition and that the woodwork of the elevator had deteriorated over time without being maintained.

It seemed like the company under Arnold had helped build up such a diversified office and residential complex along Farmington Avenue to supplement operations that now the ice business itself seemed to pull inward. New technical methods at the plant were outdone by the improvements in household refrigerators into the 1920s.

The decline can even be seen in newspaper mentions. From the 1880s to the end of World War I, the company is essentially a cultural fixture in West Hartford life; by 1923, it is left behind by more exciting talk, like roaring automobiles and modern office buildings in the Center.

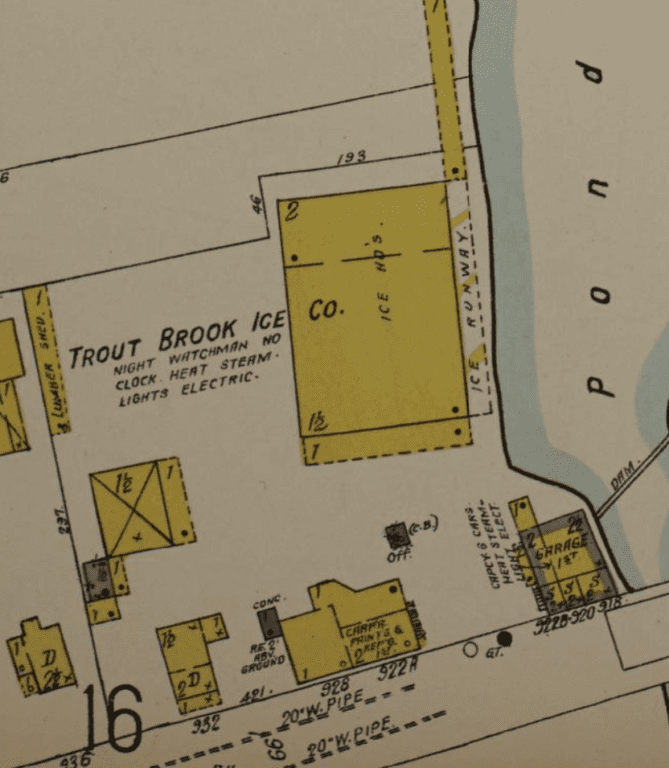

1923 map of the Trout Brook Ice Company’s plant, just 4 years before its sale

Operations continued for a while, but continued to be overshadowed by other endeavors. In 1925, the company rented out an old ice boarding house for a gas station at 932 Farmington Avenue – the property right across the street from Raymond Road on the north side.

Just two years later, in 1927, Arnold sold the Trout Brook Ice Company entirely to the Southern New England Ice Company, which had been formed to merge 30 companies serving Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts. It was a sign of the times that a massive conglomerate was being formed to consolidate and centralize these ice companies when the individual ones couldn’t work by themselves.

Many of the old buildings on the property along Trout Brook were demolished. In 1930, the State Health Department designated the pond as unfit for ice, due to the sewage that had emptied into the brook, and they were ordered to discontinue harvesting, leading to a lengthy legal battle with the town.

Once the doors closed, another section of the brook was opened for skating again to the general public. Many workers who helped flood the banks for skating in 1933 were on the payroll of the Great Depression-era Civil Works Administration. Meanwhile, the Southern New England Ice Company, which had administered the property, went bankrupt in 1936. It seems that merging operations across New England hadn’t done much to stop the death of the ice industry after all.

After Arnold sold the company in 1927, he continued in business locally. He renovated old buildings on Farmington Avenue into automobile showrooms with plate glass windows in the summer of 1928; extended his own business dealings in the Hartford area; and ultimately joined the cacophony of commercial interests along the trolley line in the Center until his death in 1945.

Many of the buildings on the property were either demolished or remodeled further for other purposes after World War II. A Shell gas station across from Raymond Road continued for many years and was eventually converted into a commercial storefront. The auto showroom next door was replaced by the new post office building in 1941, a building which still stands today.

The gas station at the northwest corner of Farmington Ave and Trout Brook Drive, which had been there since the 1920s, was demolished for the Trout Brook Flood Control Project in the early 1970s. Flooding had always been a problem along Trout Brook no matter which side of town the brook traveled through. The flood control project lowered the brook to allow it more room to rise and widened culverts.

This major restructuring forever changed the landscape of the town and remains controversial half a century later.

Finally, the two buildings constructed at 920 and 924 Farmington Avenue in the 1950s and 1960s on the original entrance to the Trout Brook Ice Company’s plant were purchased in 2020 and demolished to make way for a five-story mixed-use building.

This area’s history is proof not only of how diverse it was, but also how much turnover there is in just a lifetime and a half. Without retelling these stories, we might lose track of it all.

The buildings at 920 and 924 Farmington Avenue were demolished in 2022 for construction of a new apartment development. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

Google Street View of the current site of the Trout Brook dam and outlet to the company’s works from Farmington Avenue

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.