Officials Weigh Massive Changes in Juvenile Justice System

Audio By Carbonatix

Courtesy CTMirror.org

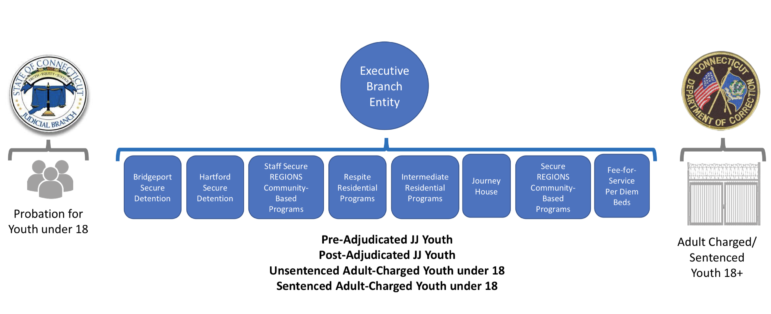

A proposal would cases involving children together in an approach taken by a majority of other states, rather than splitting cases, based on the seriousness of the crime, between the Department of Correction or the Judicial Branch.

By Kelan Lyons, CTMirror.org

In what would be a seismic shift in how Connecticut deals with children who run afoul of the law, lawmakers and officials spearheading juvenile justice reform will consider the creation of a new state agency solely for minors in the criminal justice system.

The potential restructuring is in the earliest stages of study but, as conceived, the plan would create a new entity to handle minors accused and convicted of crimes in both the juvenile and adult courts.

Connecticut’s current system for handling juvenile justice cases is bifurcated and in need of reform, officials acknowledge. Those juveniles charged with crimes serious enough to be sent to the adult courts are under the care of the state Department of Correction and held in either Manson Youth or York Correctional Institution. Those whose cases stay in the juvenile courts are overseen by the Judicial Branch, and are held in either the Hartford or Bridgeport juvenile detention centers or receive treatment in the community.

The proposal under consideration by the Juvenile Justice Policy and Oversight Committee (JJPOC) would put all of those children under the purview of a new, stand-alone state agency, an approach taken by a majority of other states. Members of JJPOC will hear a presentation detailing the proposal at their Nov. 21 meeting.

“We are very interested in system design and system reform that will align our state practices with what works for kids, and what they need,” said Sarah Eagan, the state’s child advocate and a member of JJPOC. “Kids who are high risk and high need are still kids.”

JJPOC members are required by statute to review other states’ methods for transferring juveniles to the adult criminal justice system, and how that transfer impacts public safety and affects changes in minors’ behavior. They must submit a report to lawmakers by Jan. 1, 2020 that lays out a plan to implement the changes by July 1, 2021.

The number of children in Department of Correction prisons has fallen in recent years for a variety of reasons including a lower crime rate and a slew of legislative reforms. There were 54 youths at Manson Youth and York Correctional institutions as of Nov. 1. It is not uncommon for the majority of children at Manson to be held there before they have been sentenced for their alleged crimes.

The state agency being considered by JJPOC would serve far more juveniles than those currently in the adult system. It would also manage a continuum of out-of-home placements for all youth under age 18 and oversee the detention of pre-adjudicated minors, transferring some duties from the Judicial Branch to the new Executive Branch agency.

The recommendation to create a new state agency comes from the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Children’s Law and Policy, which was hired by JJPOC to both review other states’ policies and suggest how Connecticut could improve its treatment of minors in the adult system. CCLP has already presented a preliminary version of the plan to JJPOC’s executive committee; it will be presented to the full committee at its Nov. 21 meeting.

Marc Pelka, Gov. Ned Lamont’s undersecretary of criminal justice policy and planning, said he has not yet spoken to the governor about the proposal, noting that stakeholders only found out about the recommendation earlier this month and that further analysis is needed.

“This is a crucial issue to examine, and it warrants detailed discussion and analysis,” said Pelka.

Like Pelka, top officials with the judicial and correction departments who are also members of JJPOC, said they are not yet ready to take a position on the recommendation.

“This is an important topic that deserves a thorough assessment before any decisions are made,” said DOC Commissioner Rollin Cook. “One thing you can’t do is rush this. Significant policy changes are only successful when you apply realistic time frames with a practical approach related to budget implications.”

Court Support Services Division Executive Director Gary Roberge, whose office oversees the juvenile detention centers, said his team is still analyzing the proposals. Although they will take a position eventually, he said, ultimately it’s not their decision.

“It’s going to be up to the General Assembly,” Roberge said. “They’re the decisionmakers. We don’t recommend policy. We implement policy that comes from the General Assembly.”

The Center for Children’s Law and Policy proposed four options to the juvenile justice committee, but recommended only one.

Following CCLP’s recommended path could prove to be a heavy lift. The state would have to both create a new executive branch agency and transfer responsibilities for juveniles currently undertaken by DOC and the Judicial Branch. It’s also unclear how private community placements for juveniles currently being sought by the Judicial Branch would be affected by the creation of such an agency. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, an analysis of what this would cost taxpayers has not yet been undertaken.

The new agency would assume responsibility for the 144 children under the Judicial Branch’s care as of Nov. 12, as well as the 54 youths at Manson and York.

“It’s a relatively small number of kids but at the end of the day no matter who oversees it, we don’t have the placement resources right now,” said Susan Hamilton, the director of delinquency defense and child protection for the Division of Public Defender Services. “Those would need to be developed.”

But as Connecticut Juvenile Justice Alliance Executive Director Abby Anderson suggested, the state has navigated other, difficult criminal justice reforms in the past. In 2007, for example, lawmakers raised the age of juvenile jurisdiction to 18, creating a five-year plan for phasing 16- and 17-year-olds into the juvenile justice system. Such a plan allowed officials to course correct as they phased more children into the system, Anderson said.

“We have done something like this before with a much wider and broader scope, and a much larger universe,” Anderson explained.

Other options suggested by CCLP include further consolidating the services offered by the Judicial Branch; creating a youth division within the Department of Correction; and establishing a facility co-managed by DOC and the Judicial Branch to house those in the juvenile and adult systems.

The first proposal would involve the Judicial Branch taking custody of the minors held at Manson and York. The branch is already responsible for pretrial youth in the juvenile justice system, and recently inherited responsibility for children formerly under the care of the Department of Children and Families.

The Judicial Branch has struggled since taking over for DCF to attract private vendors willing to open community-based secure facilities to care for the state’s most troubled youth. Instead, officials created a therapeutic program for children sentenced in the juvenile system that is located in the Hartford and Bridgeport juvenile detention centers, the same facilities where pre-sentenced youth are held.

“We’re barely 18 months into that process, of trying to complete the responsibility we have with respect to building a community-based network for those kids, and providing good and effective services for them,” Roberge said. “I would hope that we would have some time to do the work that we were instructed [to do.]”

CCLP’s preliminary report notes the detention centers have limited space and are not built for long-term stays. There is also a backlog of children waiting for beds to open in the detention centers’ therapeutic programs. It’s unclear how an infusion of children from Manson and York would affect those wait times.

Another option raised by CCLP involves creating a special division within DOC to care for minors in the adult system. DOC leadership would need to implement different policies, programs, training, and staffing arrangements to give youth charged and sentenced in the adult system a more developmentally appropriate environment. That method would not align with that employed by many other states, where juvenile justice agencies assume responsibility for such children.

Additionally, CCLP’s presentation states, the mission and practices of an adult prison system does not put it in the best position to work with children in a rehabilitative and developmentally appropriate way.

The final option would require DOC and the Judicial Branch to identify facilities the agencies can share to house youth in the juvenile and adult justice systems. Once minors are sent to this facility, the Judicial Branch could work to increase the number of treatment beds available in the community.

While this could assuage concerns related to long-term confinement at the juvenile detention centers and adult prisons, the report noted, there is concern it would lessen the appetite for smaller community-based programs. It would also go against national trends. No other states use this model, so there would be no system to emulate, or sources to consult for recommendations on implementation or outcomes.

As JJPOC grapples with these choices in the coming months, the U.S. Department of Justice is investigating conditions of confinement for juveniles incarcerated at Manson Youth Institution. That probe follows a scorching report from the Office of the Child Advocate that, among other things, revealed that many children with complex needs incarcerated at the prison are not receiving adequate services.

Anderson noted JJPOC can work on addressing multiple needs at the same time.

“You can address conditions of confinement needs today while you’re determining what your long-term plan is,” she said.

“This may end up being the right way to go, but we have to be planful,” Hamilton said. “We have to continue to focus on improving the conditions at [Manson] and making sure the needs of those children are met, along with pursuing changes that would keep more kids in the juvenile court.”

JJPOC co-chair Rep. Toni Walker, D-New Haven, said she’s grateful for the options, but ultimately, the committee should be more concerned with the children’s well-being than where they’re moved to.

“No matter where we house these kids,” Walker said, “we’ve got to do better.”

Reprinted with permission of The Connecticut Mirror. The author can be reached at [email protected].

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!

[…] its first public airing Thursday, officials asked a lot of questions about a plan to create a new Executive Branch agency responsible for minors in the criminal justice system but offered few clues as to their thoughts […]