School Regionalization Bills Sow Confusion, Spread Fear

Audio By Carbonatix

Courtesy of CTMirror.org

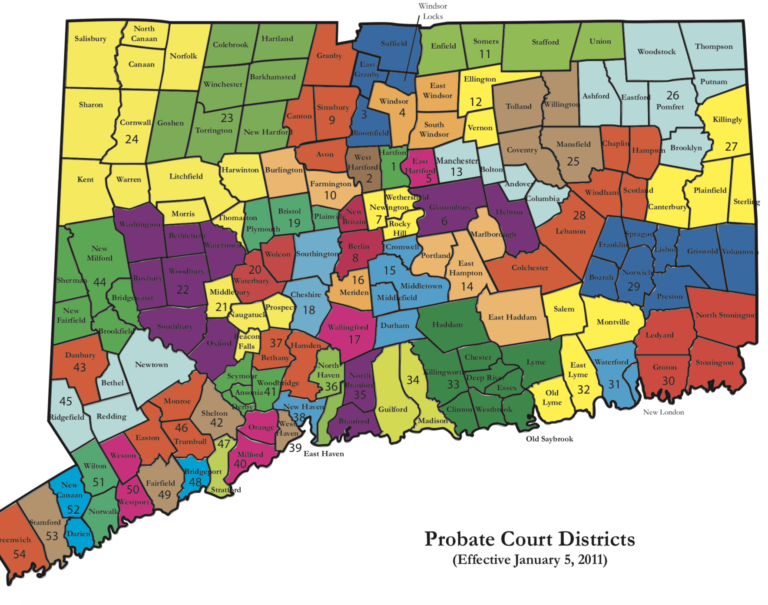

Three different ‘regionalization’ bills have been proposed, including one which realigns districts similar to the regionalized probate court districts.

By Kathleen Megan, CTMirror.org

Ever since Senate President Pro Tem Martin Looney’s controversial school regionalization bill referenced realigning districts “in a manner similar to the probate districts,” the brightly colored map delineating those court districts has been shared widely on social media by alarmed parents and educators.

“It divides Easton and Redding, which is already a Regionalized school system!” wrote one concerned parent in a Facebook post.

And, indeed the probate court map would plunder the current school districting pattern, tearing apart regional districts, creating giant districts in rural parts of the state and pairing, in some cases, bucolic small towns with cities.

But what are the chances Connecticut’s school districts will be reshaped to match the probate court map?

Probably close to nil.

Looney said he raised the issue of the probate districts simply to provide evidence that in a state where people say “broad scale regionalization” isn’t possible, “we have one counter-example” with the reduction of 117 probate court districts into 54 almost a decade ago.

Looney’s plan, Senate Bill 738, is one of three regionalization proposals under consideration by legislators. All three plans, including one from Gov. Ned Lamont, have stirred much anger and anxiety among small town residents but perhaps none so much as Looney’s bill, which specifies that it would apply to towns with total populations of fewer than 40,000. That’s all but about two dozens towns in the state.

As word has spread throughout Connecticut about the legislation, opposition has grown. The Facebook group “Hands Off Our Schools” now has more than 8,300 members, with more than 75 towns represented among its members, one of the moderators said.

Looney said in an interview last week he isn’t in any way wedded to the idea of remaking the school districts to reflect the probate districts. For instance, he said, “We wouldn’t want the small town Bethany in a regional district like Hamden,” though that is exactly what the probate map shows. Looney said it makes more sense for Bethany to stay right where it is – in Amity Regional School District 5.

However, Looney’s bill makes the probate districts the “default position,” as he said, for the school year starting July 1, 2021, if his proposed commission charged with developing a plan to implement regional school districts fails to get a plan approved by the General Assembly and signed into law by July 1, 2020.

Looney said he didn’t write the bill the way he did because he wanted to see school districts realigned to match the probate districts. Rather, he said, he wanted “to start a conversation.”

When asked why he included the probate district specifics in the bill, Looney said, “It’s because bills of general and vague content tend not to go anywhere, tend not to generate any sense of urgency.”

Not surprisingly, there are some lawmakers and residents who find this approach to writing legislation frustrating.

“It was a move to get attention and I think that’s very disrespectful to constituents, to anybody who might be worried about their district out there,” said Rep. Gail Lavielle, R-Wilton, whose Fairfield county town is a hotbed of opposition to all of the regionalization proposals.

Chris DeMuth Jr., a New Canaan resident and strong opponent of forced regionalization, said that he thinks Connecticut legislators have a habit of writing “chatty, casual bills getting them through committee and subsequently having the real work done.”

DeMuth said that while it’s okay for citizens to have conversations, lawmakers should play a different role.

To hear of lawmakers “toying with ideas that they are going to use in ways that will hurt your children is not conversation. It’s a threat,” he said.

Seeing what sticks

Residents have also complained that the other two regionalization bills are loosely written and not very well thought out.

Michelle Grady of Simsbury is also frustrated with the quality of the bills. Grady, another opponent of forced regionalization, said the bills are full of “half-cooked ideas.”

“It’s like a box of spaghetti,” Grady said. “They half cook it and throw it up against the wall to see if it sticks. That’s what this feels like.”

Lamont’s bill, Senate Bill 874, would require small districts – defined as having fewer than 10,000 residents, fewer than 2,000 students, or with only one or two elementary schools – that have their own superintendent to “receive direction concerning the supervision of [its] schools from another district’s superintendent or name a ‘chief executive officer’ to oversee the schools.”

If these districts don’t comply they could lose Education Cost Sharing funds. “The Commissioner of Education may withhold funding from any municipality … that continues to employ its own superintendent,” the proposed legislation reads.

That could happen, of course, if the bill goes through as written. But Lamont continues to insist that he wants to use a “carrot” not a “stick” to promote regionalization. Asked if withholding state funds isn’t a penalty, Lamont replied, “‘If that’s considered heavy handed maybe we do it a different way.”

Another point of confusion regarding the legislation is whether already-regionalized districts would be forced to regionalize differently. The answer to this question appears to be yes.

Looney’s bill would require regionalized districts with fewer than 40,000 residents to further regionalize to get up to that critical mass. Under Lamont’s bill, already regionalized districts with fewer than 2,000 students and 10,000 residents would be subject to the bill. Whether those districts would lose state funding if they did not regionalize would be up to the discretion of the commissioner.

A third bill, Senate Bill 457, proposed by Sen. Majority Leader Bob Duff, D-Norwalk, and Sen. Cathy Osten, D-Sprague, would require any school district with a student population of fewer than 2,000 students to join a new or existing regional district so that the total student population of the expanded district is more than 2,000. If a district is not joining a regional district, the bill says, it must inform the state Department of Education in writing about its reasons.

Parents have also raised concerns about whether schools would close or their children would be bused many miles if any of the proposed legislation becomes law. Proponents of the bills say that is not their intent. Instead, they talk about combining administrative functions, sharing resources and pooling back-office services.

Lamont, for example, has talked about districts with “too many expensive superintendents.”

On this topic, Looney notes that the Amity regional school district has four superintendents, with one each for the elementary schools in each of the participating towns – Bethany, Orange, and Woodbridge – and a fourth for the regionalized middle and high schools.

“That makes no sense at all,” he said.

But Jennifer Byars, the regional superintendent for Amity, said people may “fail to realize” all of the tasks the superintendent performs in a small town without much of a central office staff, including hiring, helping to develop a budget, overseeing special education, doing payroll and handling human resources.

She did say, however, that at a recent meeting of the superintendents and the chairman of the boards of education from each town, the majority of the people in the room thought there could be a benefit to regionalizing the district’s entire K-12 system.

Reprinted with permission of The Connecticut Mirror.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!