West Hartford’s Whistling John

Audio By Carbonatix

'Whistling' John Meyer. 1920s. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

The story of John Meyer, a hermit who for many years lived in a tent in the woods near Meadowbrook Road in West Hartford.

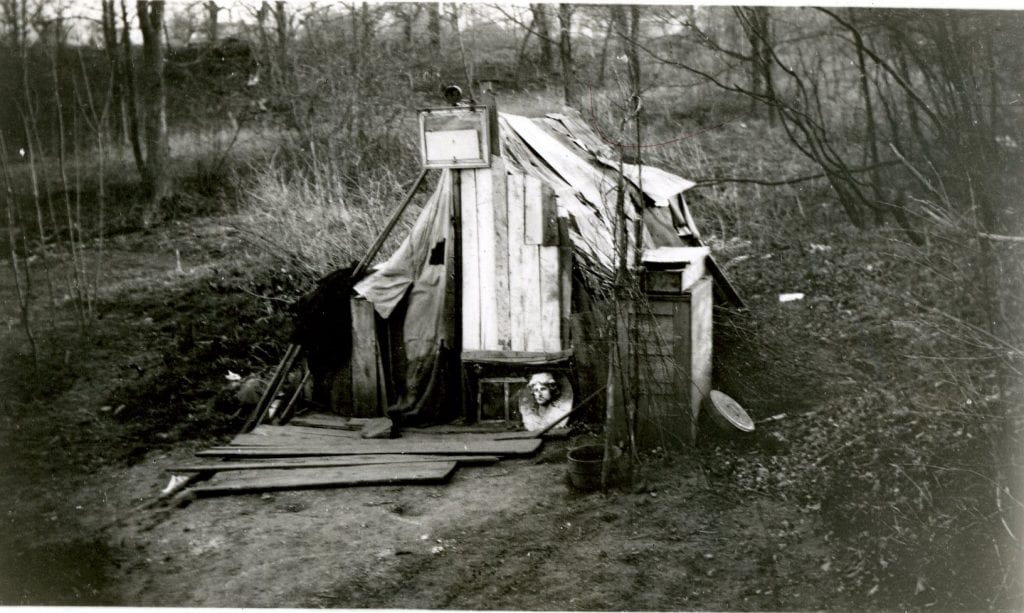

John Meyer’s makeshift home in the 1920s, a tent in the woods near Meadowbrook Road. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartaford Historical Society

By Jeff Murray

The residential section south of the Center encompasses Meadowbrook Road, a relatively calm suburban street between South Main Street and Raymond Road. As ordinary as this street is now, it’s hard to believe that less than 100 years ago, not only was it a dense forest with a running brook but it was home to a man who made a name for himself in a unique way.

John Meyer was born in 1852 in the western state of Tyrol, Austria. Following his father’s business, Meyer grew up as a shoemaker. When he was a teenager, he was conscripted into the army there and spent three years playing the cornet with the Tenth Austrian Infantry at Innsbruck. He supplemented his pay by giving concerts with other members of the band. He also worked for a time as a shoemaker there after his service in the 1870s.

In 1893, Meyer moved to the United States, first to Holyoke, MA, where his father worked in a shoe factory. While in the town, Meyer worked in paper mills, machine shops, and other factories, becoming a man of all trades. In addition, around the turn of the century he worked on several farms near New Haven and Bridgeport.

After the turn of the century, Meyer moved to Hartford, but his meager pay brought him into a cycle of homelessness. He came in contact with Hartford’s Open Hearth, a program focused on finding employment for homeless men in the city.

Meanwhile, just to the west, a carpenter had come to West Hartford in 1901 from Great Barrington, MA, looking for work. Frank J. Dellert was hired under William A. Burr, who operated a hardware store on the east side of South Main Street in the Center (where today’s Noah Webster Library now stands).

As Burr slowly turned away from the business and moved to Florida for his health, Dellert took over the store and managed it for several years. Needing a home that was in close proximity to the Center, Dellert looked to Raymond Road (then known as School Street) as a suitable site. Raymond Road had been rapidly built up over the turn of the century off Boulevard, where several light frame houses had been constructed on narrow adjacent plots of land by 1900. Dellert quickly swooped in and bought one in 1902.

While they forged two separate paths, the lives of both Dellert and Meyer would intersect after a disastrous night in 1907.

During this era, West Hartford had little, if any, protection against fires. The threat had been relatively minimal until this time. Most houses were made of heavier building materials and spaced out in long, sweeping parcels of land, so when fires did occur they were often limited to single homesteads. In addition, while the population of West Hartford steadily increased, the level of effort and bureaucracy required for adequate fire protection made the town officials hesitant to invest.

The combination of light frame homes built up in a rush on Raymond Road with lagging fire protection was a recipe for tragedy.

On Aug. 23, 1907, a Raymond Road resident was warming up dinner in her kitchen when a fire started on a small oil stove. This house, owned by Wilhelmina Engelmann, was one of four houses to the north of the Boulevard.

By the time she ushered her family outside away from the commotion, the house had already gone up in flames. Members of the volunteer hose company were sent to the scene, but the existing fire hydrants were too far away. Even when hose was extended to reach the hydrant, the pressure was too low to make an impact.

One by one, the four houses were burned severely. The only relief came from a chemical wagon that arrived from Hartford, but by then, it was too late. Dellert, who lived a few houses over, was in Branford, CT, with his family at the time and was telephoned with the bad news: his house had been burned to the ground.

While his family lived temporarily in a home on North Main Street, Dellert contracted out the work for a new house on the site of the one burned. He contacted the Open Hearth program in Hartford and requested quick help on the project. John Meyer, with his impressive work history, was sent out to West Hartford as an ideal candidate.

Dellert’s new house, a quaint Colonial, was built into the spring of 1908 and still stands today at 156 Raymond Rd. Meyer did the work of two contractors and supposedly satisfied everyone around him to the point where he never had difficulty finding employment around town. It also began a friendship between the two men that would last for 30 years.

Meyer’s first encounter with West Hartford may have been wholesome, but his one major vice brought his reputation with the other townspeople down.

Meyer’s addiction to alcohol in the years following brought him in contact many times with the town constables, who labeled him a nuisance. His criminal record lengthened with the same charges again and again: disturbing the peace, public drunkenness, and trespassing. The police considered him the most repeat offender in town, albeit harmless. He worked odd jobs around the county – he was a gardener, a lawn mower, and a fence fixer. Each year, he would leave town during the tobacco cutting season to capitalize on the business.

At first, Meyer slept in the Congregational Church’s henhouse at the back of the property. At the time, the Church stood at the southeast corner of South Main Street and Farmington Avenue. The horse sheds and hen houses backed into the rear of Raymond Road.

For a few years, Meyer remained there in what he considered a prime spot in town; however, he was asked to disperse and quickly removed to a private henhouse on Boulevard, just east of South Main Street. The owner of the home, John W. Monroe, became well acquainted with Meyer, who spent much of his spare time whistling old Austrian operas.

Meyer’s behavior soon caught the eye of the neighbors. For instance, every morning, a rooster crowed early and disturbed his sleep. All “Whistling John” wanted was to sleep undisturbed, so to solve the problem each night, Meyer caught the rooster with a bag and hung the bag on a fence. When he woke up, he’d let the rooster go about its business. Some might say it was an unspoken agreement.

Even though West Hartford had a negative view on the homeless who wandered the streets at night, Meyer became an eccentric character to those familiar with him. He was often seen walking the central streets between the Boulevard and Farmington Avenue, carrying an axe, cross-cut saw, or an article of clothing, whistling as he went. Most were happy to leave him alone, as long as he didn’t disturb them.

By 1912, he migrated from John Monroe’s home to an area south of Meadowbrook Road. At the time, that area, now the location of Thomson Road, was a small forest that separated the land of W. Wallace Thomson, who operated a greenhouse on Meadowbrook Road, from the estate of James Thomson, who owned a sprawling homestead at the northeast corner of Park Road and South Main Street. The forest was divided by a running brook that made it ideal for a roaming man like John Meyer.

Meyer maintained an outdoor camp there, doing his cooking and washing at the side of the brook. During the nights, he went back to the chicken coops and sheds of those he could get permission from. His use of the land was authorized by the owner of the tract, but it was not taken as well when a neighbor purchased a tent for him to sleep there. Many residents recognized his contributions to local laboring, but did not approve of his permanent residence in the woods beside their homes.

Nevertheless, the tent to the south of Meadowbrook Road became Meyer’s new residence. Standing 6-feet tall, Meyer had difficulty entering it, but despite this limit, he filled it with clothing, butter tubs, and boxes. He had room for a small bed in the back and a low table.

A regular attendant at church, his Catholic prayer book in German was always on the table. Over several months, Meyer took pride in his rudimentary hut, which he adorned with signs procured from a local laundry, burlap ponchos, sheet iron doors, and other irregular objects. Rough around the edges, his impending figure, some might say, was softened by his calm demeanor during the day. First-hand accounts note that he often gave whistling concerts to the birds and squirrels outside his tent in the woods. In his own words, he disliked Sundays and winters the most – he enjoyed socializing with the townspeople and emptier streets made him lonely.

During this time, Dellert continued to manage the hardware store of William A. Burr, who was living remotely in Florida for his health. He was also a member of the Fountain Hose Company, which was responsible for responding to fires in and around the Center.

The Raymond Road fire in 1907, among many others, had prompted a call for better fire protection – new fire districts were beginning to form, taking in the east end of town, Elmwood, and the Center.

In addition, the need for an organized police force was evident. Before 1900, individual constables operated on a case-by-case basis, but there was a bigger push for organized patrols and documentation. A surging population brought about denser neighborhoods, especially those in the east end of town, often in close conflict. Attractions like Luna Park became hotbeds for opportunistic criminals looking to pickpocket or start fights.

When Dellert joined the police force in 1911, the organization was still in its infancy. He was an amateur alongside veteran officers like motorcycle officer Richard O’Meara and James Livingston, the so-called hardest worked man in town.

After three years of service, Dellert had his hands full as police officer and assistant foreman of the Fountain Hose Company. By the summer of 1914, at the age of 47, Dellert bought William A. Burr’s hardware store for himself and operated the tract of land on what is now Memorial Road, consisting of several rents and some farm property. He also moved up the ranks fast. Not only was he also foreman of the Trout Brook Ice Company for nine years, he was one of the first four policemen appointed when the town created the Police Department in 1921. Within two years, he was made a Sergeant and assigned to the desk.

Dellert came face to face with his acquaintance, John Meyer, whenever Meyer made his way into the Center drunk from his tent on Meadowbrook Road. While the police made an effort to push him in the right direction, the real catalyst for change was the introduction of Prohibition in 1920.

After a rash of offenses during the wartime period, Meyer embraced Prohibition and renounced liquor entirely after that year. In fact, many of his friends said he never touched alcohol again, which gained him the sympathy of the neighbors. From his sergeant’s chair, Dellert most certainly watched Meyer’s criminal record drop off into the 1920s.

Fortunately, Meyer lived in a community that valued improvement and embraced care for those less fortunate – and most importantly, those who they believe deserved that care. His commitment to Prohibition brought him closer to the pastor of the Congregational Church, Reverend Thomas M. Hodgdon, who became a kind of mentor to Meyer. He also maintained a special relationship with those who had helped him at his beginnings – Sergeant Frank Dellert, his wife Louisa Sauer, and John W. Monroe of the Boulevard and his wife, who had given him permission to be on their land.

Many of the people in the Center came to recognize Meyer by his distinctive whistle and unique character. He was worn down by the outdoor lifestyle, however, and his tent showed the effects of age. By 1927, after living in it for over 14 years, Meyer was having difficulty maintaining the tent, which had lost its resemblance to its original form.

Therefore, that autumn, recognizing the need for better quarters, the town came together to support Meyer and the proprietor of the land he was living on, W. Wallace Thomson, took the initiative to build a one-room house 100 feet to the west of the tent on Meadowbrook Road. This house, 16 feet by 8 feet, was designed to be waterproof and withstand the elements.

By December, Thomson helped Meyer move his furniture from his rickety tent to his new residence. The town hall janitor took it upon himself as well to donate a table and some chairs. Sgt. Dellert led the police to provide Meyer with transportation and a new bed.

It was a concerted effort to pay back a man who had contributed positively to the community. It also provided Meyer with a newfound sense of hope. He told those helping him that he was even contemplating getting back into his old trade as a shoemaker.

With his troubled past behind him, Meyer continued his life as a hermit south of Meadowbrook Road in his small cabin. In the fall of 1933, he had settled in and was still very much in touch with the wildlife around his home. A squirrel’s nest had been made on top of his roof, a sight he would have enjoyed.

On the morning of Nov. 26, 1933, Meyer attended mass at St. Thomas’s Church and shortly after had a conversation with the wife of John Monroe near the Boulevard. When he reached his cabin on Meadowbrook Road around noon, he grabbed a rough ladder and set it against the walls in order to climb up to see the squirrel’s nest. Suddenly, he was struck by heart failure and he dropped dead outside next to the entrance. His death was mourned especially hard by those he considered “special friends.”

Eventually, Meyer’s cabin was torn down and the traces of its existence were wiped away with the construction of new houses on the south side of Meadowbrook Road in the latter half of the decade.

Almost poetically, the career of Dellert was also winding down. The year that Meyer passed, he retired from the police force after 27 years as constable and policeman, and settled down with his wife, Louisa, at 156 Raymond Rd. His retirement lasted shorter than expected, however; in 1939, he was involved in an automobile accident at the corner of Boulevard and Whiting Lane, and he was sent to the hospital. Just a few days later, Dellert died in the hospital as a result of his injuries.

It has been eight decades since the days of that West Hartford. Our connection to those events feels a million years away – the generations are so far removed from the present day and the landscape that surrounded the Meyer tent is unrecognizable now. The brook he lived beside has been filled in, new houses have been built, and new streets have been laid out. Even Raymond Road, at the time a channel between the bustling Center and the residential vision of the Boulevard, now feels like an ordinary side street shrouded with trees.

We’re unaware of the influential people who once walked the streets in town and the lives they led. Even something as simple as the people of West Hartford building up a house for a man who was once a nuisance can resonate. In a way, those people in 1927 West Hartford are no different than we are today.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!

Thank you for sharing information about West Hartford’s past residents. It’s good to be aware of our town’s history.

Wonderful story. Thank you for including this on we-ha.com.

Frank Dellert in this story is my fraternal great grandfather.

I’d love to share this story with my fellow descendants of Frank.