From the West Hartford Archives: Park Road and Oakwood Avenue

Audio By Carbonatix

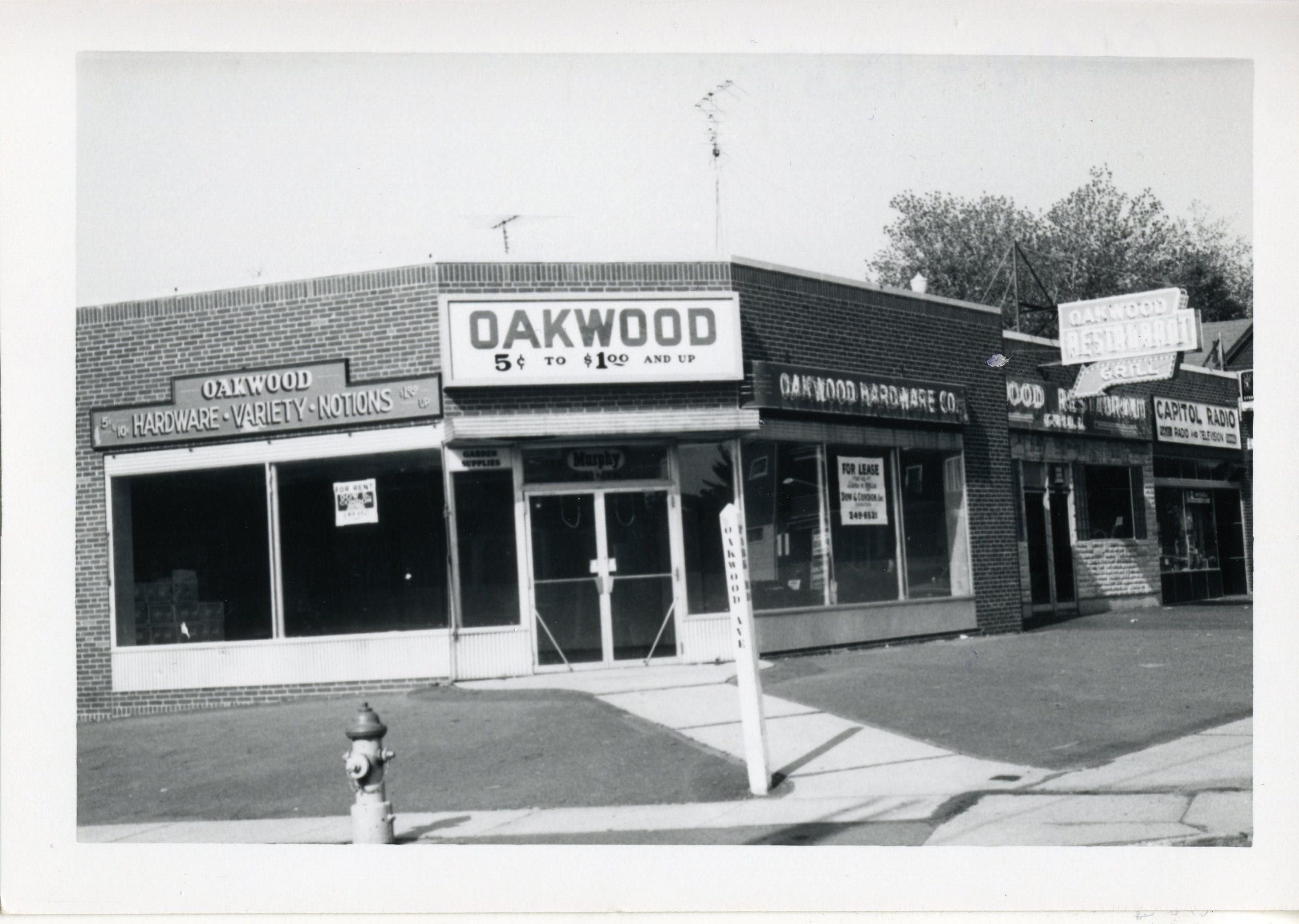

Southwest Corner of Park Road and Oakwood Avenue. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This is a view of the southwest corner of Park Road and Oakwood Avenue in the 1960s.

The area south of Park Road between Oakwood Avenue and what is now Washington Circle was owned by Frederick A. Mitchell, a Civil War veteran who grew up and lived in a house nearby. He enlisted in Company D, 22nd Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers and saw service in the war. After he returned, he went into the milk business for 20 years and then was hired by the United States Stamped Envelope Works in Hartford.

In the early 1890s, he moved to Farmington Avenue west of the Center and sold his house on Park Road. The property at Park Road and Oakwood Avenue came into the hands of real estate developer Frederick Rockwell, who was consolidating land holdings in the area, especially along the Boulevard to the north. Rockwell sold the corner lot at 175 Park Road in 1896 to John C. Wilson, a carpenter who had emigrated from England in 1861, and his wife Virginia Favreau, a French Canadian.

The Wilsons built a double house at the southwest corner in the fall of 1896 and moved in with their five children. The lot the house was built on extended back along Oakwood Avenue for 200 feet and set the future boundary for the commercial block that would be constructed on this corner decades later. Wilson could have chosen to subdivide the lot for other houses to be rented out or sold off, which could have potentially changed the course of this corner’s history. Instead, the long lot endured and the family lived there for more than 30 years.

John died at the home in 1924 at the age of 73, leaving his wife and six sons, who had all moved out besides his youngest, Louis. The estate would own the house for another 20 years.

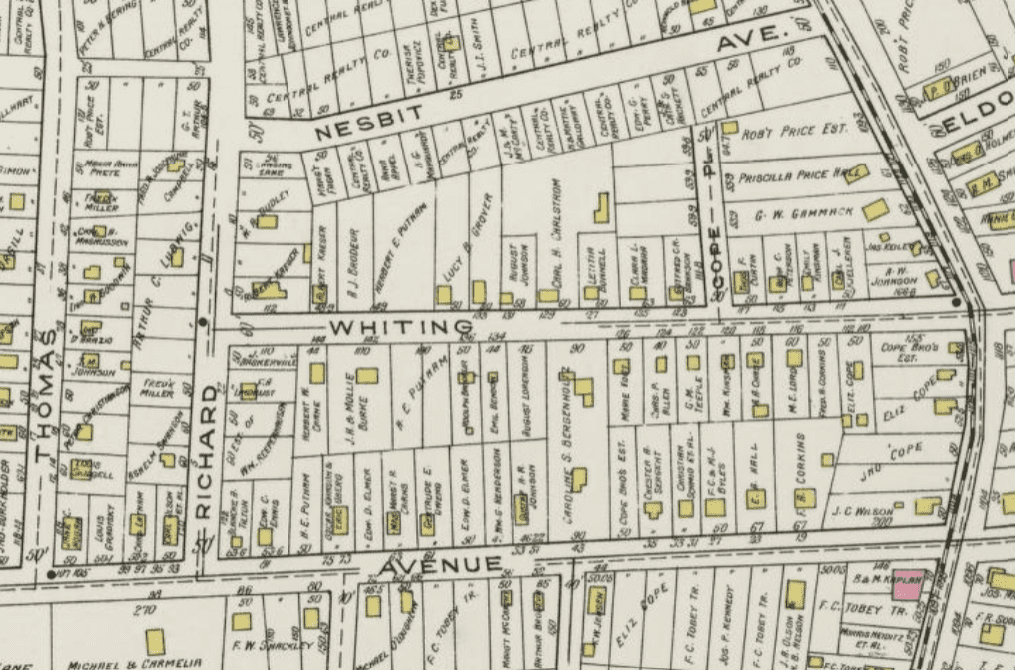

When the Wilsons moved into the upper part of the new double house in 1896, they rented out the lower floor to Louis A. Richards, who would also leave his mark on the area. Richards was a market gardener from Meriden who had just started the business on Oakwood Avenue down the road. Over the next few years, Richards bought up land on the west side and laid out by 1898 the streets known as Richard Street and Thomas Street for new houses.

By 1907, the land had been almost completely sold off. Today, Richard and Thomas Streets are all connected with 1920s developments, like Price Boulevard and South Quaker Lane, but it was originally an isolated cluster of lots and houses. Richards’ market garden and short stint on the lower floor of the Wilson house at the corner of Park Road provided a foothold for this small suburban development along Oakwood Avenue.

Map of the area in 1909, including Thomas and Richard Streets along Oakwood Avenue to Park Road

Frederick Rockwell, who had owned the land surrounding the Wilson house on the south side of Park Road, also made a contribution to the landscape. Whiting Lane had originally stopped at Park Road as it led south from Farmington Avenue, so Rockwell decided to extend it out south of Park Road to the edge of his property at what is now 253/255 Whiting Lane on the west side and 252 Whiting Lane on the east side. When this was laid out, it was known as Whiting Lane Extension, although today the name has been simplified to just Whiting Lane to align it with its main artery north.

A tiny street was also laid out west of Whiting Lane Extension on what is now Mitchell Place. It was originally named Cope Place after long-time landowners in the Oakwood Avenue area (the Cope Brothers). In 1923, the town voted to change the name to Mitchell Place, probably in honor of Frederick Mitchell, who had owned the land for many years before. Frederick was also still alive when the name change was made and would live almost another 10 years after.

In between the Rockwell property on Park Road and the Richards subdivision on Oakwood Avenue was the land of Arthur J. Brodeur, a Massachusetts-born French Canadian builder. Brodeur originally came to West Hartford in 1899 when he bought a single lot on Oakwood Ave and built himself a house near the corner of Crosby Street. Over time, he bought up a significant amount of property for new houses and he later expanded to other neighborhoods. He was one of the petitioners in 1904 for the paving of Oakwood Avenue and became instrumental in town politics. He was active on the Democratic Town Committee, which consisted of many other neighbors in the larger Quaker Lane area, where the party held a lot of sway.

When Brodeur retired from building, his family continued in the occupation for some time. He moved to Old Lyme Shores, where he died in 1938.

In 1912, Brodeur, whose land had adjoined the end of Rockwell’s Whiting Lane Extension, connected it even further west to Richard Street, opening the road through his land on Oakwood Avenue. The increased building in the area of Whiting Lane, Seymour Avenue, Thomas Street, and Richard Street increased the migration of people into West Hartford, many from Sweden and Denmark, necessitated the opening of this street through his land, and made a new school between Charter Oak and the East School much more urgent – this became the justification for the new Seymour Avenue School (now Smith STEM School). The Hartford Courant estimated that there were 50 houses that had been built in the area just from 1911 to 1913. This building boom, which continued for several more years, can be seen today in the number of WWI-era bungalows that popped up in this neighborhood.

Map of the area in 1917, showing the extension of Whiting Lane through to Richard Street

It’s sometimes hard to believe that from the Mitchell farm in the 1890s to the time of John C. Wilson’s death in 1924 at the corner of Oakwood Avenue and Park Road, the neighborhood had seen such an intense growth. Rockwell had steadily sold off his holdings on the south side of Park Road to individual owners, who either built houses in the early 1900s or just held the lots for investment.

The land next door to the Wilson’s corner house was owned by one such investor until he sold it in 1915 at the height of the building boom. This land would later be sold to a developer in 1929, who built a store next door at 179 Park Road.

The Wilson estate owned the house at 175 Park Road through 1944 when it was sold to Liljedahl Brothers, contractors, who made plans to develop the corner, as the property was zoned for business. The Liljedahl family still owns the property at the corner after nearly 80 years.

The house was removed to make way for the new business block at the corner in 1950, in which the Oakwood Hardware Company store opened that spring. For its celebratory opening, the store gave away free flowers to the women, screwdrivers to the men, and candy to the kids. The construction of this corner building was just one small part of the wave of commercial establishments along Park Road from Prospect Avenue to South Quaker Lane built from the 1930s onwards.

After only about two decades, the store closed and the Clothes Horse had its grand opening in its place at the corner as the Junior League’s thrift shop in 1972. While this store closed after 45 years at the site in 2018, it was an icon for those decades it stood there and retains its legacy in the community today.

The Second Chance Shop, a mission of the The Village for Families & Children, opened at that location in early 2019.

The Second Chance Shop, photographed in 2022, is located at 175 Park Rd., West Hartford. Photo credit: Ronni Newton (we-ha.com file photo)

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.