From the West Hartford Archives: The History Of The MDC Reservoirs

Audio By Carbonatix

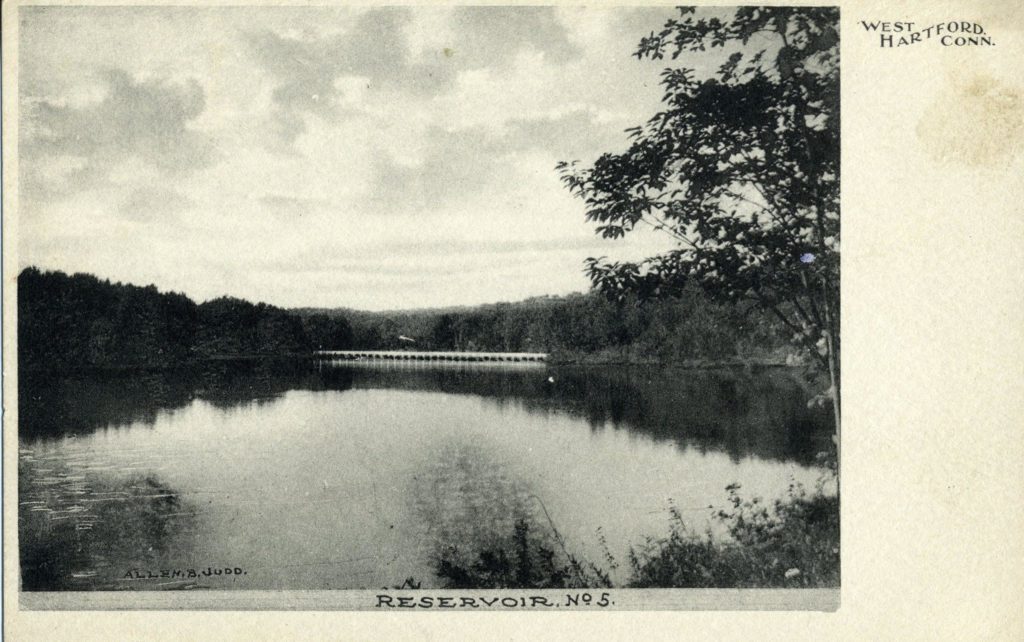

Photo Credit: Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

The growth of the City of Hartford in the mid-1800s prompted a demand for more water supply. By 1859, the city was laying three hundred service pipes a year. The water supply in the city was inadequate – it couldn’t get enough to high points or to some fire hydrants, and even couldn’t get to the second floor of some buildings. A report by the city’s water board recommended a new water source in the western hills of West Hartford, which could be supplied to the city by gravity. The water board gradually bought up the pasture and woodland in this area through the 1860s.

Some of this land had been used by residents for local water consumption or for mill operations, and those residents petitioned against its construction. They were outnumbered by those in favor, though and in 1866, work went ahead. 32 acres of land in town were flooded after Trout Brook was dammed in order to provide the City of Hartford’s 30,000 residents exclusively with water. The construction work was done by the historically nameless and, if the demographics of the later reservoir laborers give us any hint, it was probably done by a combination of poor city workers, “drifters”, and immigrants, particularly from Ireland and mainland Europe. It opened in January 1867 with a capacity of 165 million gallons.

What followed was a grueling legal battle between West Hartford and Hartford over the cost of access. West Hartford residents believed that their land had been taken for the water supply and, therefore, they should be able to get it for free. It was decided by the courts that West Hartford people would have to pay the same rates as those in Hartford.

What followed was a grueling legal battle between West Hartford and Hartford over the cost of access. West Hartford residents believed that their land had been taken for the water supply and, therefore, they should be able to get it for free. It was decided by the courts that West Hartford people would have to pay the same rates as those in Hartford.

The resentment from some locals towards the city “taking” the water without due compensation would continue for many years, but William Hall argues in his 1930 book that this spurred the creation of West Hartford’s own water system after all. What worsened the attitudes of locals was a massive rainstorm in September 1867, just eight months after the reservoir had opened, which burst the newly built dam and flooded the town along the line of Trout Brook all the way to North Main Street near Fern Street. It destroyed bridges and gristmills and took years to rebuild and recover. Hartford had to foot the bill for damages to the town for roads, bridges, and business lost.

Water consumption in the Hartford area continued steadily, though, and almost immediately after, the water board looked to build other reservoirs in the area to supplement the first one. Reservoir 2 was built in 1868 (just a year after), followed by reservoir 3 in 1875, reservoir 4 in 1880, and reservoir 5 in 1884. Reservoir 4 was later abandoned and removed. All of these bodies of water led into the one distributing reservoir (#1) on Farmington Avenue, making it a key focal point for visitors.

Over the years, the linkages between the west end of town and the city of Hartford grew stronger. By 1882, telephone communication was established between the distributing reservoir and the Hartford water commissioners’ office. Some laborers stayed on site for continuous work. For example, James Smith, an immigrant from Ireland, lived in a house next to the reservoir and was employed as a gatekeeper in the 1870s, earning $540 per year. Later, William E. Johnson, an engineer with the water board since 1890, served as division superintendent for the whole reservoir property until his retirement in 1936.

The reservoirs had been a picturesque spot for leisure since at least the 1880s, offering an escape from city life with just a trip along Farmington Avenue. The construction of the electric trolley line in 1894 to Unionville supercharged demand though and highlighted the real estate opportunities. In the fall of 1895, a real estate development company bought the Stanley farm right across the street and laid out the first official suburban tract in West Hartford – Buena Vista.

Summer cottages and permanent homes were built first along Farmington Avenue right across from the reservoir and then later on the top of the hill with a view towards Hartford. Farmington Avenue, in this section, became almost a physical marker for the gap in wealth. While many were able to leave the city and build their own houses on Buena Vista and others could freely stroll through the park and pleasure ride along the waters, the trolley line and reservoir system were a constant reminder of the physical burden on the working class.

Summer cottages and permanent homes were built first along Farmington Avenue right across from the reservoir and then later on the top of the hill with a view towards Hartford. Farmington Avenue, in this section, became almost a physical marker for the gap in wealth. While many were able to leave the city and build their own houses on Buena Vista and others could freely stroll through the park and pleasure ride along the waters, the trolley line and reservoir system were a constant reminder of the physical burden on the working class.

The trolley required dozens of laborers to lay track day after day and dig out the surrounding land to allow passage for the trolley cars. When it snowed, the trolley would be backed up for miles, and the company had to send out a hundred or more shovelers in the middle of the night to relieve the “embargo.”

When Reservoir 6 was built in the 1890s north of Albany Avenue, the newspaper would comment on the wave of Polish immigrants and homeless “tramps” traveling to the waterworks for seasonal jobs. In the summer of 1896, Italian immigrants digging a trench and laying a new water main from the reservoir attacked the new foreman who had come to oversee the work and had evidently tried to change things up. A small riot broke out, two men were immediately fired, and a strike was threatened (although it never went forward after others refused to participate). Ethnic strife between Austrian and Irish workers at the reservoirs was common. Others capitalized on the crowds and set up shop near temporary housing or by the reservoir entrance to sell alcohol. Police visits were part of the status quo.

Nonetheless, the reservoirs were improved over the years, and maintenance became more organized. By World War I, water flow across the system was made more effective, concrete bridges were built, and walls were raised to hold more water. With the advent of the automobile and its adoption by many residents into the 1920s, new houses were built on Buena Vista’s subdivision, many of the lots having been held as an investment since the 1890s. Later, bungalows were built in the woods around the reservoirs.

In 1929, the Metropolitan District Commission was established to replace the Hartford Water Board. It included seven member towns, but not West Hartford, which eventually joined the regional body after intense political debate and a referendum in the 1980s. Water supply to other towns in the Hartford area has expanded over the decades and since MDC’s establishment, water has come from Barkhamsted’s reservoir through pipes to West Hartford and Bloomfield.

The reservoir area showcases how some things change and others stay the same. Economic conditions were made better over the years and technology that has built on previous innovations has made all this work much easier, even if it’s more bureaucratic. From 1867 to now, there is clear progress in how West Hartford gets its water. But social and political tensions are as sharp as they were then; several labor and wealth classes continue to coexist uneasily in the same town; different visions of progress duke it out every month; and time marches on regardless.”

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Excellent article, good job by all. If residents are interested in an even more in-depth analysis of the development of our reservoir systems (and the 1867 flood) please read WATER FOR HARTFORD, The Story of the Hartford Water Works and the (sic) MDC. Written by Kevin Murphy and available on Amazon (Kindle only $ 3.99, hard and soft considerably more expensive, 352 pages), it is an in depth look at the contentious politics of several eras of the “water wars”.

Perhaps not so different from today’s politics.

Bill Gleason

Excellent Article Jeff. Informative as always!