From the West Hartford Archives: The Origin of Talcott Junior High School

Audio By Carbonatix

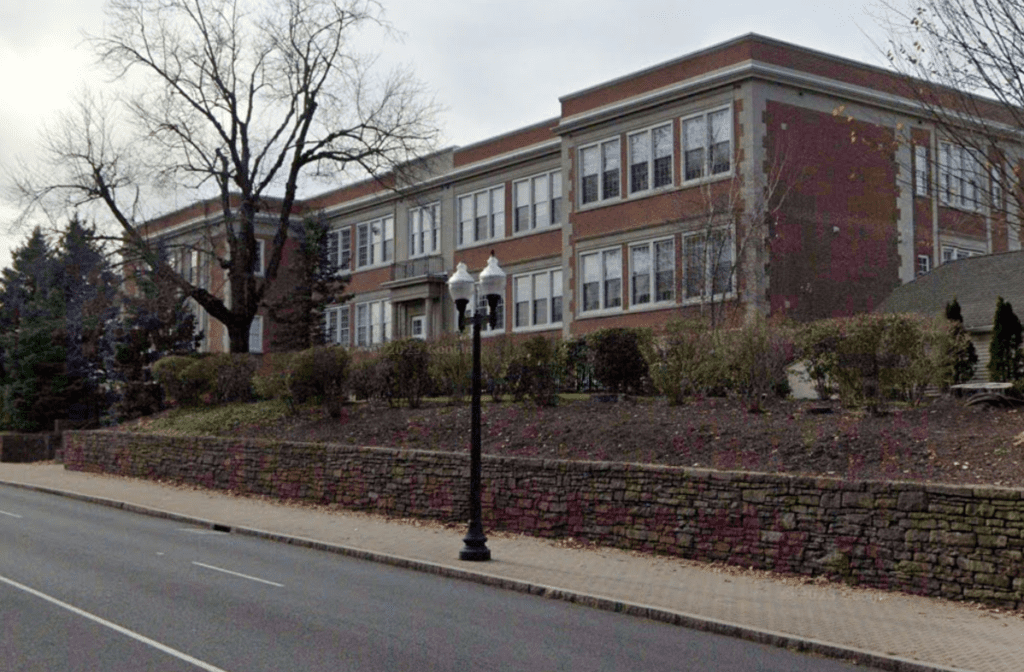

Talcott Junior High School. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

Talcott Junior High School was built during a time of massive growth of schools in West Hartford, second only to what later took place in the 1950s. The population of the town had nearly doubled from 1910 to 1920 and was set to triple in the following decade.

In the 1910s, the U.S. saw significant developments in the roles of women in governance, specifically in schools. The growing women’s suffrage movement, combined with the attitude towards top-down government involvement, put an emphasis on the school system. Many women were attending colleges and universities and began to assume leadership roles as school administrators outside of their normal positions as teachers.

Although women could not vote until the 19th Amendment in 1920, they could vote in Connecticut’s local and school elections. The emphasis on the education system brought many women to register in the spring of 1917, calling for better pay for teachers and more cooperation under Parent-Teacher Associations. The building boom the town had been experiencing created a demand for more schools and other facilities, meaning the school board was an incredibly important group during this time.

In February 1918, 40 registered women rallied around Constance Marshall as Republican nominee for the school board, bringing the “men who believed that the efforts of the women should be recognized” on board. The men opposed believed that in such a critical time for West Hartford, a man was needed to ensure the new high school was overseen correctly.

Nearly 100 women registered just weeks before the election.

In a heavily Republican town, Marshall’s election to the school board sailed through. Margaret Turner was also elected. Both women joined their first meeting on the board in April 1918 to discuss the pressing issues of the day: rising prices for school supplies; better infrastructure for gyms and playgrounds; and the organization of the schools within the town, including a brand new high school.

Just four years prior, Superintendent of Schools William Hall had called for the reorganization of the school system to introduce junior high schools as an intermediate between the grammar schools and the high school in the Center. With the growth of the town’s population, it would become necessary to manage the school population better, although it would be painful.

In the fall of 1918, after a summer of raising teacher salaries and choosing a site for the new Hall High School in the Center, the school system faced the influenza pandemic. The pandemic had created a number of teacher vacancies by sickness that did not let up even after they weathered the storm in the spring of 1919. High school senior girls took over as substitute teachers for a short while, but Principal Bugbee continued to have trouble finding teachers. The town seemed to be hurtling towards a serious issue – fewer teachers, vastly more students, and not enough school buildings.

In March 1919, it was acknowledged that the East School (at Whiting Lane) and the Elmwood School (at Woodlawn Street) would be too crowded for normal operations and would have to possibly add on portable buildings or double up classroom sessions. Portable buildings were voted on that summer to accommodate the overflow of students (and until they arrived, some grades just did not attend school!). It wasn’t enough though, as 230 students were being added nearly every year, making a total of 1,806 by 1920.

Talcott Junior High School as seen in the 1950s. Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

It was the Parent-Teacher Associations that gained influence during this time. The Elmwood PTA held multiple meetings through the winter of 1919-1920 that held galvanize support for brand new school buildings rather than temporary fixes. The school committee voted to introduce junior high schools called for by William Hall more than six years prior.

Plans for a junior high school in Elmwood were agreed to and the town bought the land at the northwest corner of South Quaker Lane and New Britain Avenue from the Talcott family. In January 1921, a vote to appropriate funding to build two schools – Talcott Junior High School and Plant Junior High School – shockingly failed due to what a school board member called “lack of intelligent and persistent leadership,” “failure to foresee” school population growth, and a group of residents whose “property interests demanded a low tax rate rather than a sufficient and modern school plant.” After much outrage, another meeting was held and the school committee, backed by 350 voters, successfully pressured the finance board.

These sister schools were named for Alfred Plant, the secretary of the Town School Committee who died just before Plant Junior High was built, and James Talcott, owner of the land and whose family had made many direct financial contributions to the education system.

Work started immediately on Talcott and it opened in 1922. While the school no longer exists, the building still stands as a monument to the active participation of nearly every sector of society in the middle of West Hartford’s postwar educational crisis.

The former Talcott Junior High School is now part of the Quaker Green condominium complex. Google Street view

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

Talcott closed due to lack of enrollment in the late 70s-early 80s. Was sold to Coleco and had a strong connection to the Cabbage Patch fad. Ames took over and left and the building became a flash point in the early 90’s K2-35 school reorganization controversy. Shaw’s grocery stores bought the property and became a tremendous rallying point for Elmwood that ultimate lead to development of the TND, or Traditional Neighborhood Design standard in our zoning code. Shaw’s was defeated but the concurrent Home Depot development went through over tremendous neighborhood protest. Enormous BOE meetings and Town Council meetings were packed with citizen sporting anti K2-35 and “What’s the Master Plan” buttons for months. The Dems lost both the Board and the Council elections for the first time since the Westfarms Mall/Piper Brook backlash 15 years earlier. It took several developers and applications to get the present School House Square project passed. Saving the Talcott facade and the development of the Bourgoine pocket park area on the corner, where the above pictures show a 1950s parking lot, were key to the passage. Rick Liftig played(s) an important positive role in the park area.

Haha! In a pre-digital age, one week the West Hartford News was 3 sections and 89 pages long!