Witness Stones Project: Students Find and Share an Untold History of the Enslaved People of West Hartford

Audio By Carbonatix

Retired educators (from left) Denise deMello, Elizabeth Devine, and Town Historian Tracey Wilson. Photo credit: Lisa Brisson (we-ha.com file photo)

The Witness Stones Project, which launched in West Hartford during the 2017-18 academic year is involving students at multiple grade levels and adding previously un-accounted information about the enslaved to the town’s historical record.

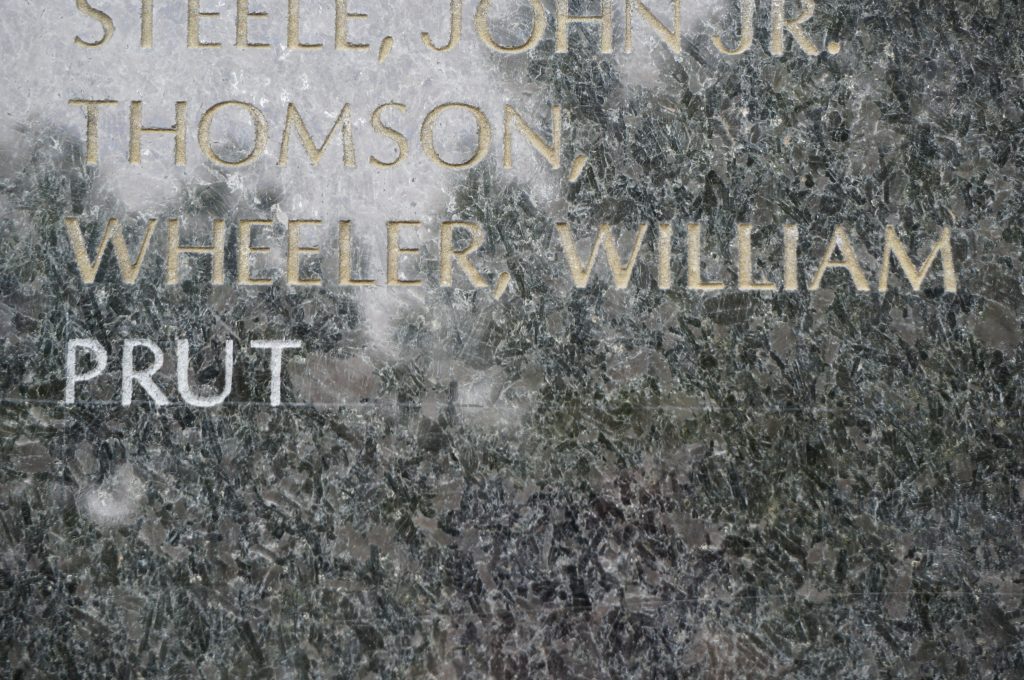

Prut’s name engraved on the Revolutionary War memorial at the Connecticut Veterans Memorial in West Hartford Center. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

By Ronni Newton

History involves the study of what happened in the past, but we all know there is more than one side to most stories.

There are also stories that have yet to be told.

When Tracey Wilson and Liz Devine started the Witness Stones Project in West Hartford, they wanted to find those stories, the stories about the lives of the enslaved people who are a part of the town’s history. People whose made contributions that few, if any, know about today. They wanted to acknowledge that slavery existed in West Hartford, and commemorate the lives of those who were enslaved while at the same time inspiring community conversation.

From left: Denise deMello, Elizabeth Devine, and Town Historian Tracey stand by the Underground Railroad marker near the headstone of Bristow in Old Center Cemetery. Photo credit: Lisa Brisson

Wilson, a retired social studies teacher from Conard high school, is also town historian. Devine is a retired social studies teacher from Hall High School. Their goal was not just to add another dimension to West Hartford’s history, but to also involve students as active learners in the process. Retired King Philip Middle School library media specialist Denise deMello got involved as one of the project directors for the second phase of the Witness Stones Project.

Today’s West Hartford is a community with a diverse population, one where more than 70 languages are spoken in the public schools, a place where human rights are celebrated. While it seems inconceivable that slavery ever existed in West Hartford, in fact some of the town’s most prominent families – the Sedgwicks, Goodmans, Coltons, Hookers, Hosmers, and others – were slaveowners.

And while the names of those families are peppered throughout the town’s historical records, and roads and buildings are named after them, the stories of the men and women they enslaved have been largely forgotten.

The project has far exceeded her expectations, Devine said. “It’s really morphed.”

“We really want students to be in the position of historians,” Wilson said, and that’s exactly what has happened.

Devine and Wilson provide the primary sources, but the students are the ones who develop the stories of the enslaved, and tell them in a way that provides context and meaning. The sources include church records, wills, inventories, account books, genealogical records, and gravestones.

Sedgwick Middle School students, led by drummer Curtis Greenidge, process from First Church to Old Center Cemetery for the installation of temporary witness stones in May 2019. The engraved stones were installed over the summer. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

The first phase of the Witness Stones Project was presented in the fall of 2018, and started the previous spring when 42 students in Sean O’Connor’s AP U.S. History class at Conard began researching the lives of George, who was enslaved by Timothy Goodman, and Jude, who was enslaved by Stephen Sedgwick. They also studied more about Bristow, the namesake of West Hartford’s Bristow Middle School and at that time the only African American to have a headstone in the town’s Old Center Cemetery.

The students worked to answer the question: “Why bear witness to slavery in West Hartford?” and shared their research in written form as well as through a public program held Sept. 26, 2018 at First Church West Hartford.

Actual stones – the witness stones – were then placed near Bristow’s gravestone in the Old Center Cemetery.

During the following academic year, the project expanded to include research into 10 more enslaved people and involved more than 750 students. Eighth graders at West Hartford’s three public middle schools, fifth-graders at Renbrook School, high school students from Conard and Kingswood Oxford School, and sixth and seventh graders at Solomon Schechter School all participated in the research and in presenting their stories in various forms – poems, blogs, articles, artwork, podcasts, and more.

This past summer the 10 additional witness stones were permanently installed in the Old Center Cemetery, with the names of Simone, Pompey, Ben, Page, Prut, Chris, Hannibal, Caesar, Hercules, and Bristow joining George and Jude. The stones have been placed next to the existing Bristow headstone as visible reminders of West Hartford’s past. Whatever dates could be found were engraved on the stones – including birth and death (when it could be determined) as well as the date of baptism – along with the names of the enslaved person’s owner or owners. Bristow’s stone notes that he bought his freedom in 1775.

Stone carver Marc Boucher carved Prut’s name into the Revolutionary War section of the Veterans Memorial in West Hartford on May 23. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

The Renbrook fifth graders were also involved in a side project – getting Prut’s name placed on the Revolutionary War memorial at the Veterans Memorial in the Center, acknowledging his service. Three of the students presented their case to the Town Council, and just before Memorial Day Prut’s name was engraved on the stone. During the town’s Memorial Day ceremony, Wilson and two Renbrook students shared Prut’s story.

“As town historian what I want is for more people to know that there was slavery here,” Wilson said. “It’s so much more powerful to do it through the students.”

“The fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth graders, they really can do a lot,” Devine said. As educators, that’s been one of the most meaningful benefits of the project.

“They pick things up that we didn’t while looking through the documents,” Devine said, like the role the enslaved may have had in building some of the houses that still stand today.

This drawing by King Philip Middle School student Sarah Chandler represents the “dehumanization” of slavery through the use of the runaway ads and how they described the people. She wrote in her description of the drawing: “Strong and Healthy,” “Wench,” and “Prime and Healthy” are all used to describe the enslaved persons in Connecticut, and I used these on the chains in my drawing to show how the slaves were regarded as property or livestock, in a very dehumanizing way.

One King Philip eighth grader created a song that she composed and sang at the presentation of the research. “It’s so moving to listen to, and hear what she had taken from the study,” Wilson said.

Another King Philip student created a drawing of a Connecticut flag that included chains filled with words depicting the dehumanization of the enslaved.

“I want to remember Caesar, for all the pain you went through. Some could call you a hero for everything you would do …” wrote Sedgwick student Sharandeep Kaur in her poem dedicated to Caesar.

The Solomon Schechter students wrote an apology.

While the students have found the project interesting and fun, it’s also thought-provoking – and disturbing. “But the idea of giving them some humanity is important,” Devine said.

The students now understand that slavery is about “power, oppression, and race,” Wilson said.

“It’s risky, really hard to teach about,” said Wilson. Not only is it hard to find the information, but it can also be hard to talk about.

Wilson said when dealing with an issue like slavery there’s the fear of saying the wrong thing – calling someone out rather than calling them in. The students of color may react differently, and the teachers have to be ready and open to their reactions.

“If we look at the big picture the kids are seeing history in a different way,” said Wilson, and so is she. “I now go by Goodman Green differently [the triangle of land on South Main Street in the center of West Hartford, opposite First Church].”

Devine noted the quote from Anne Farrow’s “The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory” that appears at the top of the Witness Stones Project website: “Slavery is the landscape that you learn to see.”

“To me that says it all,” Devine said. “It doesn’t mean you look at the town in a negative way. We just need to know. It’s important to understand history.”

From the research conducted thus far, it appears as if there were at least 25 slaveowners, enslaving more than 62 people in West Hartford between the 1690s and the 1820s. Some of the enslaved people ran away, others were freed, and many likely died while still listed as official property of their owners.

The Witness Stones Project is continuing this academic year, with more students getting involved in recording the town’s history. Students from all three of West Hartford’s public middle schools, Kingswood Oxford juniors, Renbrook fifth-graders, and Solomon Schechter eighth-graders will share with the community what they learn about additional enslaved people whose previously untold stories are nevertheless and integral part of the fabric of West Hartford’s history.

The Foundation for West Hartford Public Schools “Frank Webb Home Grant,” has providing funding for the work by eighth graders on this project at Bristow, King Philip, and Sedgwick middle schools.

West Hartford Assistant Superintendent Paul Vicinus, speaking at one of the installation ceremonies last spring, thanked the students for having the courage to dig deeply and have an authentic learning experience. “Hopefully for you it demonstrates that education is so much more than just showing up to class,” he said.

Vicinus realized, from reviewing the research that the students had done, that the unit Prut served in during the Revolutionary War became the U.S. Army unit he personally serves in today. The project has created connections for him and for the town, and has created something new that will be part of West Hartford’s history going forward.

The Witness Stones Project has been funded through a Connecticut Humanities Council grant, and other donors including Jane Lehman and Matt Winter and the Sandy and Arnold Chase Foundation. The Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society, First Church West Hartford, and West Hartford Public Schools have donated time and resources to the project as well.

In Connecticut, the Witness Stones Project began in Guilford in 2017, led by Adams Middle School teacher Dennis Culliton. His work was the inspiration for the Witness Stones Project in West Harford, and he mentored the project team.

Internationally, the project actually has its origins in the Stolpersteine Project, which began in Germany in 1992 and has spread to 22 European countries, where “stumbling stones” were placed outside of the last known residences of Holocaust victims.

For detailed information about each enslaved person, and the presentations by the students, visit the West Hartford Witness Stones website.

Close-up of Prut’s name engraved on the Revolutionary War memorial at the Connecticut Veterans Memorial in West Hartford Center. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Information developed about enslaved people in West Hartford during the 2018-2019 academic year:

Ben: Baptized in 1759. One of at least eight people enslaved by Col. John Whiting, he was passed along to John Whiting Jr., who lived at 291 North Main St.

Pompey: Also enslaved by Col. John Whiting, he was willed to Whiting’s wife and then his son, Jerusha Whiting.

Page: Also enslaved by Col. John Whiting. Baptized Aug. 16, 1741. Passed on to Daniel Skinner in Whiting’s will.

Chris: Baptized in 1758, he was enslaved by Rev. Benjamin Colton, who lived at 25 Sedgwick Rd., and Abijah Colton.

Prut: Enslaved by John Whitman Jr. He died in 1776 at Fort Ticonderoga. His name was engraved on the Revolutionary War memorial at the Connecticut Veterans Memorial in West Hartford in May 2019.

Hannibal: Enslaved by Capt. Thomas Hosmer and Thomas Hosmer, Esq. Baptized in 1738, freed in 1777, and died in 1780.

Caesar: A tailor, Caesar was enslaved by Capt. Thomas Hosmer and Ann Prentiss Hosmer.

Hercules: Enslaved by Capt. Thomas Hosmer and Thomas Hosmer, Esq. He was born in 1729, baptized in 1742, and died in 1761.

Simone: Enslaved by and kept house for Capt. Thomas Hosmer and Ann Prentiss Hosmer. Her mother’s name was Rachel.

Bristow: Born in Africa in 1731, Bristow was enslaved by farmer/mill owner Thomas Hart Hooker. He bought his freedom in 1775 and died in 1814. Bristow Middle School was named after him. Bristow’s gravestone is located in the Old Center Cemetery, and the witness stones have been installed in the same area.

In 2017-2018, students researched the lives of George and Jude:

Jude: Born c.1753, and originally enslaved by Stephen Sedgwick Sr. who passed him down to his son, Stephen Sedgwick Jr. He was listed in an inventory that also included 110 acres of land, 20 cows, 45 sheep, 13 swine, five horses, one bull, and two yokes of oxen. Jude ran away in 1774 and despite the offer of a $20 reward, was never returned.

George: Born c.1730 and baptized in 1758, he was enslaved by Timothy Goodman, who lived at 567 South Quaker Lane, owned a post office and a tavern in the part of town now known as Bishops Corner, and is the namesake of Goodman Green – the triangle of land at the southern end of the intersection of South Main Street and Farmington Avenue. Researchers could not determine when George died, but did not find any notice indicating that he had run away.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford!

[…] June 2019, we placed 12 stones for George, Jude, Chris, Hannibal, Caesar, Hercules, Simone, Bristow,… near Bristow’s gravestone. We hope to install 12 more this year. One of the key components of the […]

[…] noted the Witness Stone Project in the town’s public schools under the auspices of the Noah Webster House, which was introduced […]

[…] When Tracey Wilson and Liz Devine started the Witness Stones Project in West Hartford, they wanted to find those stories, the stories about the lives of the enslaved people who are a part of the town’s history. People whose made contributions that few, if any, know about today. They wanted to acknowledge that slavery existed in West Hartford, and commemorate the lives of those who were enslaved while at the same time inspiring community conversation. Continue reading. […]

[…] their research for the Witness Stones Project, Aliza and Regina discovered shocking truths about the history of slavery in town. There were about […]